In her review of the 2025 Canyon Grizl, Hailey Moore discusses how this updated frameset fits into the growing bifurcation we’re seeing between race optimization and adventurability in the gravel bike category. Hailey also gives an in-depth take on why she thinks her review build—the Grizl CF 8 with ECLIPS—detracts from an otherwise impressive platform.

These days it is not enough to label a bike as simply a gravel bike. The 3T Racemax² Italia and Trek CheckOUT are both technically capital “g” Gravel bikes, though their respective design intents couldn’t be more different under the off-road umbrella. Similar to the subclassification of mountain bikes, as the gravel category has broadened many brands have further delineated the specialization of their models. In place of subcategories like downcountry or enduro, today’s gravel bikes are increasingly being segmented based on race-performance prowess versus an aptitude for adventure rides and bikepacking.

What is gravel bike?

As a relatively young bicycle manufacturer, Canyon created this split in their line early on, introducing the Grail as the German brand’s race-focused frameset in 2018, followed by the launch of their all-around, long-haul counterpart, the first-generation Grizl in 2021. Last summer, Canyon released an updated Grizl frame with geo changes that plant it more firmly in the adventure-rig space. The 2025 Canyon Grizl also comes in two build-kit “families” that add another layer of taxonomy for would-be buyers to navigate.

I received the most specialized, or perhaps niche-ified, complete Grizl available in the US to review, the Grizl CF 8 ESC with ECLIPS system, and have put some considerable test miles on it over a couple seasons. While I’ve been impressed with the ride quality and the handling of the Grizl platform, some of Canyon’s design decisions for this bikepacking-specific build have left me wondering how much pre-production testing this bike saw outside the studio and in the real world.

2025 Canyon Grizl Update

Most of the changes seen in the 2025 Grizl update fall into two camps: increasing the bike’s comfort and stability while also introducing more standardization in the bike’s spec (more on this later, but this platform does still involve componentry exclusive to the Canyon ecosystem).

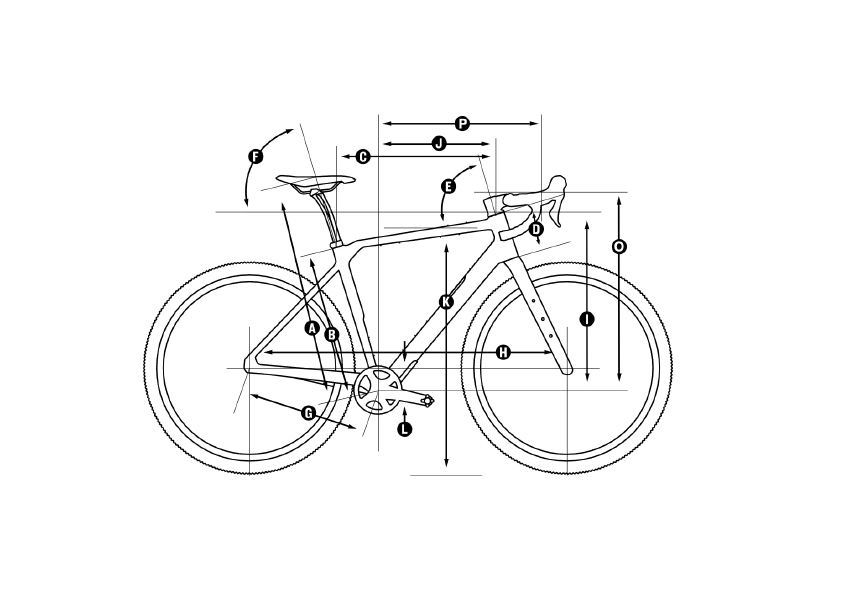

In the frame, Canyon made adjustments to the carbon layup at the headtube and chainstays to improve durability and efficiency; the toptube was raised to create more front-triangle space to better accommodate a frame bag and bottles; the rear dropouts are now UDH compatible; and, by eliminating the frame’s front derailleur mount and slightly elevating the driveside chainstay, Canyon increased the Grizl’s tire clearance from 50 mm to 54 mm (front and rear). Canyon also upgraded the Arcos headset with triple-sealed stainless steel bearings, claiming the change increases the bearings’ longevity tenfold.

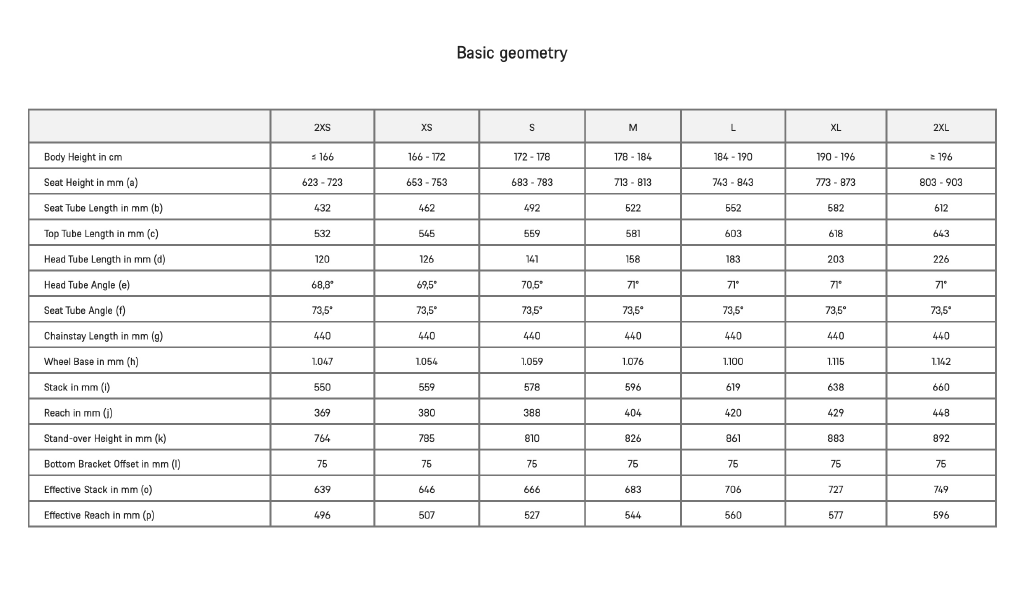

Geo tweaks make the 2025 Grizl a little longer while nudging the rider into a more upright position—changes that put more distance between the Grizl and the Grail. In addition to raising the stack, Canyon pushed up the trail by slackening the HTA and lengthening the front center. The chainstays grew to a lengthy 440 mm across sizes, an adjustment that plays into that larger tire clearance while also allowing all sizes to come specced with 700c wheels (previously, the smallest two sizes were designed around 650b).

The earlier Grizl had a couple of wonky specs—a 1 ¼” steerer tube and an internal sleeve-tightening system instead of an external seatpost collar, tensioned via a bolt on the back of the seattube near the seatstay junction. The steerer size elicited predictable frustration among those trying to swap stems, and the integrated seatpost tech resulted in reported creaking and, as some riders complained, damage to the seatpost.

For the 2025 update, Canyon made the smart choice to walk both of these idiosyncrasies back. The latest Grizl’s FK0143 fork features the widely adopted 1 ⅛” to 1 ½” tapered steerer tube spec, and the frame uses a standard external seatpost clamp. Despite these capitulations to more mainstream preferences, Canyon kept the Grizl’s pressfit bottom bracket, doubling down on their argument in favor of this spec for its increased stiffness and the extra space it creates around the BB cluster without having to bow out the chainstays.

2025 Canyon Grizl Quick Hits:

- Seven sizes: 2XS to 2XL

- 700c wheels across sizes

- Increased tire clearance to 54 mm front and rear (up from 50 mm)

- 1x only

- UDH compatible

- LOAD downtube compartment for tool storage, or to house ECLIPS battery (depending on build)

- Eight total complete options in two build “families”

- Five OG (Original Graveller) build kits, and three Escape builds kits.

- Three complete bikes available in US

- FK0143 Fork has three pack mounts

- Multiple bottle bosses across the frame; non-traditional rack mounts designed to work with Canyon’s custom racks

- Semi-integrated cable routing

- Canyon custom add-on accessories include: fenders, front and rear racks, half-frame and handlebar bags.

- Prices for US-available builds range from: $2,099 to $4,699

2025 Canyon Grizl CF 8 ESC w/ ECLIPS Build Spec

As the acronym-packed name suggests, the Grizl build I received for review has a lot going on. For this update, Canyon divided their complete builds into two families—the OG builds (Original Graveller) and the Escape Builds.

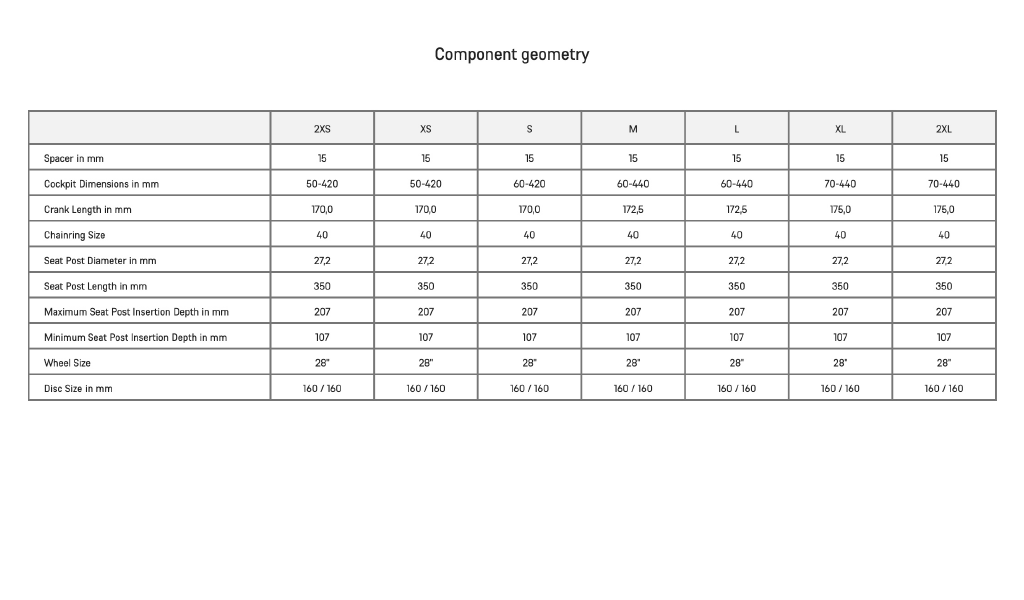

In short, OG builds reflect the needs of today’s gravel normie, and nothing more: a conventional cockpit setup, SRAM Apex 12-speed groupset with an 11-44t cassette range (Rival and Shimano Di2 upgrades on builds not available in the US), fast-rolling 45-millimeter Schwalbe G-One RX Pro tires, and a downtube storage compartment. Most of these builds come specced with a DT Swiss LN alloy wheelset, though top tier OG builds get upgraded to Canyon’s own new GR30 carbon wheelset.

ECLIPS

The Escape build family is where Canyon decided to flex a little more engineering savoir faire by seeking to preemptively solve common bikepacking setup dilemmas: the “Fully Mounty” cockpit features a mini aero-extension loop that provides alternative hand positions and additional up-front accessory mounting real estate; the Shimano GRX mullet drivetrain with an 10-51t cassette range offers more-forgiving gearing than the OG builds for loaded riding; the (somewhat) burlier 45-millimeter Schwalbe G-One Overland Pro tires boast better traction; and—the pièce de résistance—the Endless Charge and Lighting Integrated Power System (ECLIPS) promises self-sustaining light.

By employing a buffer battery to capture and store the energy from the dynamo hub, rather than the hub feeding directly into the front light, ECLIPS seeks to refine the DIY dynamo-powered lighting setup that many bikepackers use. Using an intermediary battery bank allows for more consistent lighting power (as opposed to the problem of dynamo-powered lights flickering at slow speeds) while also allowing the buffer battery to potentially be used to charge other electronics when lights aren’t needed.

To achieve this, ECLIPS is built with some desirable upgrades: an included SON 29 S front dynamo hub—where connection terminals integrated into the front dropouts eliminate the need for an external wire—is connected to a Lupine Smartcore 3,500 mAh battery housed in the Grizl’s LOAD downtube storage compartment. The battery is then wired—internally, invisibly—to front and rear lights, a 1,000-lumen Lupine Nano SL that is secured to the Fully Mounty aero extension, and a 45-lumen Lupine C14 light integrated into the seatpost clamp (note that because blinking tail lights are not legal everywhere, this light blazes a solid red when on). At 20 kph (or about 13 mph) the battery recharges at a rate of 12% per hour, faster when the rider’s speed increases. Lastly, ECLIPS includes an input/output USB-C port on the steerer column’s non-driveside to top off the buffer battery between rides.

So now that we’ve gotten through all the tech specs and marketing jargon, you might be wondering: how did the bike actually ride?

First Ride Impressions

I received the Grizl CF 8 ESC at a Canyon media event in Boulder, CO, in June 2025. Interestingly, Canyon set up individual meetings and rides with each of the journalists the brand met with in the Front Range. I’ll admit that I appreciated the more personal tone this considered approach lent to my time with the two Canyon employees (one engineer, one from marketing) who had flown in from overseas, and their two PR reps. My first ride on the review Grizl doubled as a chance to play tour guide by taking the Canyon team on my favorite loop from town, a mixed-surface climb up to the old mining hamlet-turned cycling destination of Gold Hill.

From the outset, I could tell that I loved the Grizl platform. The size XS felt about perfect for my 5’7” frame (the smallest size is 2XS). I felt well within the bike without it feeling like a crowded race fit or, conversely, feeling like the bike was too long beneath me, like some touring bikes I’ve pedaled.

Views from Gold Hill. Photos: Josh Weinberg

I had never ridden the earlier Grizl (or any other Canyon bike) and, although some have lamented that the updated Grizl’s longer wheelbase and more upright position compromise its climbing ability, I personally didn’t feel hindered by the geometry, given the type of versatile bike the Grizl purports to be. It’s not a race bike and, in fact, for an adventure and bikepacking-focused bike, I thought it climbed quite well. Maybe this can, in part, be attributed to the specifics of the Grizl’s carbon layup, or maybe Canyon’s case for the pressfit bottom bracket—with its increased stiffness and stronger, straight-line chainstays—was bearing out.

My opinion of the Grizl platform continued to improve throughout the duration of that first ride—after a sustained climb, our loop closed with a whooping descent that follows tight gravel switchbacks to more flowy and sweeping paved turns. While I was duly impressed with the Grizl’s climbing competency, the bike is truly a delight on descents. The geometry felt like it could willingly keep pace with any speed I wished to carry—somehow the longer wheelbase managed to feel playful but predictable, planted but precise.

Additionally, I found that the specced Canyon S15 VCLS 2.0 CF seatpost—which advertises 20 mm of travel—added to the riding experience by dampening much of the underwheel chatter on bumpy surfaces. When my time with the Canyon team came to an end, I was excited to take this bike home with me for some extended riding.

Long-term Impressions

Throughout the summer and fall, I probably abused my media privileges by logging nearly 1,000 miles on my review Grizl. It should be telling that as a daily mixed-surface driver, it was the bike that I was consistently motivated to take out. Although the geometry may not be optimized for climbing, importantly the bike doesn’t feel sluggish while pedaling uphill, and given its game nature on descents, over the course of my time with the Grizl I found its capabilities very balanced on the whole. For daily riding, the Grizl is an easy choice.

Bikepacking

Ironically, it was when I outfitted the Grizl for bikepacking that I started to form some criticisms of the build spec, despite the fact that this Escape with ECLIPS build is tailored to multi-day bicycle travel.

FidLock QuickLoader Grizl Half-Frame Bag

Although not included in the complete build, Canyon outfitted my review bike with one of their custom half-frame bags (the LOAD FidLock QuickLoader Grizl, $159.95). The FidLock closure system utilizes three magnetic bolts, located on the underside of the toptube, to “lock” the bag in place through a kind of slide-and-snap movement. Daisy-chain webbing on the bottom of the bag provides finger loops with which to quickly disengage the FidLock and free the bag from the frame.

Theoretically, this seems like a hassle-free improvement to time-consuming bolt-on, lace-up, or velcro-strap bag attachment systems. And, at first glance, the easy access exterior flap pocket of the LOAD half-frame greatly appealed to me as a handy design detail. Unfortunately, in practice I found the FidLock attachment hilariously flimsy, and, after having the bag pop off the frame multiple times while out riding, I ultimately shelved it early on in my review period.

Overnighter to the Oregon Coast in September with dad.

Packing the Grizl CF 8 ESC w/ ECLIPS

Making use of the Grizl’s frame space thus proved a challenge for the two overnighters I did with the bike. Although a small wedge bag might work in the front of the triangle, I found the shape of the seatstay-toptube junction was incompatible with other full or half-frame bags I own (including bags from Revelate, Oveja Negra, and Swift Industries). When packing up the Grizl, I ultimately reserved the front triangle for bottles only. The Grizl does feature rack mounts, but they are designed specifically for use with Canyon’s bespoke front and rear racks (which I did not have). To carry my gear, I relied on a large Oveja Negra seatbag, bar roll, JPacks stem bag, and my favorite Andrew the Maker mini panniers.

Mini Review of the Full Mounty Cockpit

During my many day rides on the Grizl, I had periodically dropped into the aero extensions of the Full Mounty cockpit (a design that feels inspired by RedShift’s Kitchen Sink bars) either on my forearms to give my hands a break, or just to tuck in a bit out of a headwind. If my review Grizl had been a short-term rental, a bike that I didn’t get to know through day-in and day-out riding, I might find the Full Mounty clever, or at worst remain neutral. But ultimately—for me over the long term—the limitations that “fixed” cockpit setups like these impose generally outweigh their advertised convenience.

Because the Full Mounty’s drop bars, aero extensions, and stem are all part of the same piece of carbon, there is almost zero minute adjustability available. Of course you can still move the position of the hoods, but that’s it. Changing the actual angle of the drops (an adjustment I would have liked to make on my review bike), isn’t possible, nor is changing the angle of the aero extensions, or the stem length without ordering a fully different bar from Canyon (which currently doesn’t appear to be available under their site’s Parts & Accessories category).

Plus, while the alternative hand position offered here is sufficient for short-term reprieve, it is no substitute for the relief and comfort of being able to rest on the elbow pads and longer arms of full aero bars. To be clear, the aero extension of the Full Mounty isn’t trying to be an aero-bar replacement, though it’s important to know that most bikepackers might opt to attach full aero bars atop the Fully Mounty extension. Is that still a clean and convenient solution? Maybe!

Per the name, the front of the aero extension loop does provide some bonus surface area for mounting gadgets, but the oblique angle of the bars where they join at the steerer tube (in lieu of a standard stem) actually eliminates some of the space that a traditional bar would provide in the untaped clamp area. I noticed this especially when trying to run my go-to everyday carry handlebar bag, the Swift Industries Kestrel. The width of the aero extensions made strapping the Kestrel on the outsides of the loop a bit of a stretch, and trying to strap the bag inside the loop was just weird. For bikepacking, I found a bar roll best suited to ride in this finicky cargo area, though Canyon also offers a custom snackbag to fit in the aero-extension’s negative space.

Most veteran bikepackers I’ve talked to are neurotic about their bike setups—seasons of trial and error have bestowed on them strong opinions about what works and what doesn’t and how critical it is to eliminate minor irritants, the frustration of which can compound into unneeded mental stress during long tours or competitive events. Experienced bikepackers I’ve known often take intense pride in the setup solutions they’ve developed over the years—each rider’s bike in some way becomes a reflection of their own experience and ingenuity. While the Full Mounty offers a compelling template to work from—especially for less-experienced riders or those with less tolerance for tinkering—I do think that it eliminates some of the rider’s creative control in outfitting the cockpit area. In a sense, some of the agency here has been outsourced to Canyon, and it’s up to the rider to decide if the decisions made in this less-customizable Grizl build will work with their riding preferences.

ECLIPS: Seamless Lighting Solution or Black Box?

The Grizl’s ECLIPS was the feature of the build I was most excited to test; it feels like a natural evolution in Canyon’s commitment to innovate. Offering an off-the-shelf bike with a built-in lighting system designed for bikepacking makes a lot of sense, given how ubiquitous dynamo upgrades are in touring and bikepacking circles. It also shows that Canyon is actively keeping their finger on the pulse of multiple sides of the cycling industry.

A system that eliminates the need to remove lights from your bike for charging seems like it would also have a secondary appeal to commuters with an interest in riding gravel. I’m not sure if Canyon had the commuter demographic in mind when designing the Grizl ECLIPS build, but I think this crossover functionality further bolsters the Grizl’s claim to versatility outside of racing.

For the first couple of months that I rode the Grizl, ECLIPS worked as advertised. Even in the daytime, I appreciated having the added visibility of the solid red rear light (a button on the Full Mounty cockpit toggles through brightness-level settings for front light). Canyon has an app that allows riders to view the battery level of their ECLIPS, but given that my review bike was pre-production, I was never able to sync it with the app. Still, every couple of rides or so, I’d bring the Grizl inside and plug it into the wall via the steerer-tube USB-C port to top of the battery.

A late-summer Treehouse Cyclery group ride; photos: (left) Hailey Moore and (center, right) River Cyr (IG: @awanderingriver)

Then, one day on a late-summer evening group ride, as I rolled over the top of our climb and started down a paved descent in the quickly fading dusk, the front light didn’t come on. Of course, since I’d been able to reliably count on the ECLIPS-powered front and rear lights up until this point, I hadn’t brought along any supplemental lights. All told, no catastrophe ensued since I was with a group of friends on well-lit bikes, but having the Grizl’s front light fail in that moment shook my faith in the system. Unfortunately, my review bike’s ECLIPS has worked inconsistently since then (for both front and rear lights). When I reached out to Canyon about the issue, they allowed that the glitch may be a result of a pre-production build, so I’m not sure how much stock to put into this system failure—YMMV.

Assuming that my pre-production ECLIPS build was faulty, and that issue was resolved before launch, I would still have reservations about the system’s charging ability for long—and especially remote—trips. The Lupine Smartcore battery that’s stored in the Grizl’s downtube has a 3,500 mAh power capacity. Factoring in the small amount of power that is used and lost in energy transfer, this offers roughly—as Canyon states—enough juice to charge an iPhone battery once from empty to full. For context, on multi-day trips when my partner and I want to rely on a power bank for multiple phone charges (while assuming that we may not get to recharge the power bank), we typically carry a 10,000 mAh power bank.

The SON 29 S front dynamo hub provides enough power to recharge the Lupine Smartcore at a rate of 12% an hour when riding about 13 mph (or 20 kph), and it can power both lights—without drawing on the battery—at a speed of ~9 mph (15 kph). Without consulting someone far better at math than I am, my intuitive worry is the system doesn’t offer enough power storage in the battery to be relied upon for more than running the front and rear lights, given that riding a loaded bike means more time spent riding at slower speeds. Perhaps internal downtube space was a limiting factor, but I wonder why Canyon didn’t opt for even a 5,000 mAh battery to ensure a little more margin when undertaking routes with a lot of vertical gain—and thus limited time for the dynamo to recharge the battery—or through remote terrain with little access to external power sources.

If I were keeping this Grizl build, I would opt to carry a small supplemental power bank to charge electronics while (hopefully) relying on ECLIPS solely for running lights. Lastly, I think this also makes more practical sense for the lived experience of bikepacking, as the first thing I do when I stop for a coffee or meal is start charging electronics. Pull up to a cafe and leave the bike outside (maybe plugged into a sneaky wall outlet), but grab your supplemental battery bank to bring inside with you, to either charge from the wall, or top-off devices that have been in-use on the bike.

In Closing

Despite all of the components and build specifics that I addressed individually in this review, I don’t want to undersell how much I enjoyed riding this bike. For a day-to-day platform that you want to use to push the limits of “gravel,” the Grizl is impressive in the way it maintains some degree of peppy performance while also offering a measure of sure-footed stability and ample clearance. For me, one of the unfussy OG builds would be an easy sell. Like hearing the demo version of a song and then wondering why the album version got over produced, I think that this build spec may have gotten over-complicated by some whiz-bang features. Stripping back the extras and returning some of the setup decision making to the rider is where I think this bike would most shine.

Pros

- Dialed geo offers a fun and balanced ride for both climbing and descending

- Updated to standard steerer tube and seatpost specs

- Hard to beat the DTC price points

- Full Mounty and ECLIPS build specs may appeal to those just getting into bikepacking

Cons

- Limited cockpit adjustability with Full Mounty bars

- FidLock half-frame mounting system sucks

- Red rear light stays on when charging

See more at canyon.com.