Note: A long piece with GIFs. Best viewed on desktop with a good connection.

Also: I don’t know if the timing of this piece is good, given the AO is on and this is technique-heavy, but maybe for those that read it, you can cast your eye on this year’s field and pick up on some things discussed.

“It is our belief that energy efficiency is the absolute criterion for survival.”

— The Spinal Engine, by Serge Gracovetsky

In Death of a Forehand – Part I I highlighted forehand swing trends in nextgen players. Setups had the racquet tip pointing sideways, sometimes paired with a flexed wrist.

I proposed that Nextgen forehands required more movement in the wrist than is necessary, as well as having to “undo” more of the swing into the slot position by starting the racquet head a long way outside the slot position, thus making the shot prone to timing issues. Nikola Aracic of Intuitive Tennis does a good job visually explaining the differences below, and watching the whole video is helpful for reading the rest of this piece:

Part I finished with the suggestion that del Potro’s Vetruvian modern swing was still the ideal form, and yet, Jannik Sinner’s outside whip once again topped the Tennis Insights forehand shot quality metric (and the eye test) for the 2025 season.

While Sinner does maintain an extended wrist, setting up with the racquet tip on the outside presents the Italian with no issues. As Nikola explains, we can’t say Sinner’s technique is poor if he’s absolutely melting the ball with absurd spin, power, and consistency! Given this, the original Death of a Forehand theory needs a better explanation:

Arno’s question was from a Gill Gross Mailbag that didn’t get answered, but it’s a good one! My explanations have drifted because they weren’t very good, and because the philosophy is to try and predict how swings will shape tactics and results.

This post attempts a better explanation.

“Fallibilism entails not looking to authorities but instead acknowledging that we may always be mistaken, and trying to correct errors. We do so by seeking good explanations – explanations that are hard to vary in the sense that changing the details would ruin the explanation.”

— David Deutsch, The Beginning of Infinity

To do that, I’m going to nest this analysis within the P.A.S principles, which stand for:

The P.A.S. Principles…are based on the physics of the ball-racquet interaction. They directly determine what the ball does (or doesn’t) do… Every shot in tennis is a ‘recipe’ combining varying degrees of each P.A.S. Principle.

When focusing on the racquet face, great forehands today tend to have:

-

More of an in-to-out path, rather than too little.

-

A wrist position (and racquet face angle) in the setup that coincides closely with contact, rather than one that must hinge more.

-

More racquet head speed, rather than less.

Let’s dig in.

“In complex areas of human performance such as tennis science, there will always be a gap between the working or coaching opinion and what can be supported by scientific evidence.”

— Duane Knudson, Biomechanical Principles of Tennis Technique

Let’s start by taking a more critical look at Sinner’s forehand. While he sets up with his racquet-head on the outside of his hand, pay attention to how long Sinner’s path is from his slot position by virtue of his overall backswing length and how well he produces lag (how far the racquet tip is behind, or inside, the hand):

If we look at some of the players with an outside and flexed setup, notice how anaemic their slot position is even with neutral balls. The racquet tip does not lag inside hand and point to the back left as much as Sinner. They aren’t rushed or abbreviating their swings in these instances; this is their swing.

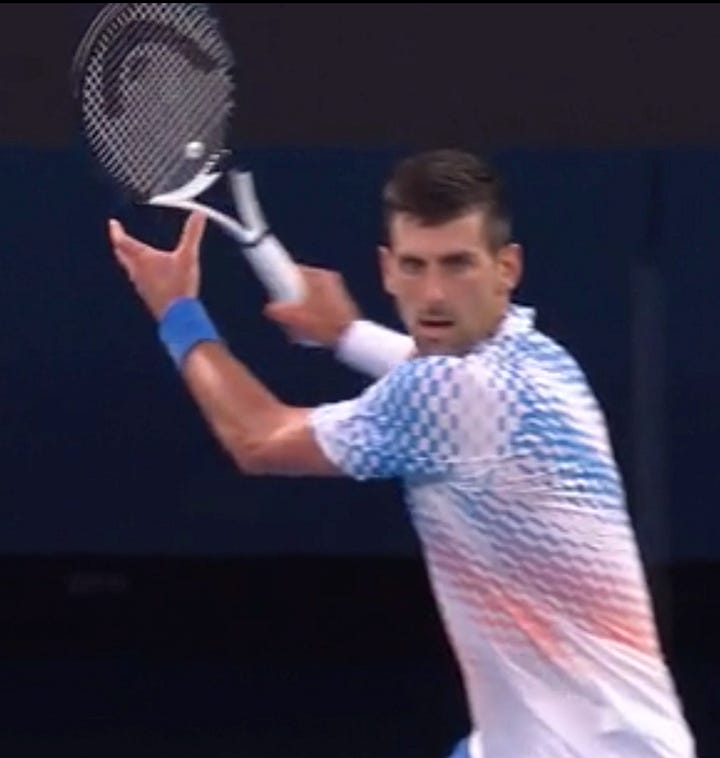

And if you watch Sinner, Djokovic, Alcaraz, Tsitsipas, Fils, you’ll see they often achieve deeper slot positions than those shown above:

A still comparison of what a strong slot position looks like against a weak one:

And go watch all the Paul/Hurkacz/Tiafoe/Machac footage you like. They rarely achieve this degree of slot position:

Some would laud the Paul swing as being more compact, and suggest that timing the ball would be easier for the American, but I think this undersells the importance of racquet head speed as it relates to timing and efficiency, especially for semi-western and western grips. Additionally, I think what is defining the current era is the ability to attack while defending; “neutral” is dying, and a great deal of racquet head speed is required to keep up.

Part I contended that having an extended wrist in the setup will make timing the ball easier given contact is made with wrist extension (caveat for more extreme Western grips, where contact is made with more flexion). This isn’t new or my idea at all, but it’s one I still subscribe to.

“Decreasing the number of body segments and the extent of their motion will increase the accuracy of the movement.”

— Biomechanical Principles of Tennis Technique, by Duane Knudson

However, I believe the benefits of wrist extension extend (no pun intended) beyond racquet face control, and also assist the more important elements of racquet path and speed.

Racquet-head speed is the currency of shot performance. The more you have, the more you can trade for spin and power. The modern forehand builds speed by emphasising gravity on the drop, with the racquet head starting above the hand (del Potro). The Nextgen forehand builds speed by emphasising the “flip” — the right-to-left movement of the racquet head is more severe. Crucially, both can create a great stretch in the chest and arm muscles and a deep in-to-out swing path.

Given we are dealing with humans and not machines, there are an endless variety of swings, and labelling them into broad categories (“nextgen”, “modern”) really only scratches the surface and misses numerous other swing-specific factors that may influence shot outcomes (wrist positions, grips, timing and range-of-motion of body segments). In saying that, when it comes to racquet head speed, there are three main ways we can increase it with swing mechanics:

-

Use gravity:

“My friend and physicist Dr. Pat Keating has found that on the free-falling loop, the racket head gains approximately 5.5 mph on the first foot of the drop: then multiply 5.5 times the square root of the height of the drop. The result is the speed of the racket due to gravity. This increased racket speed has a multiple effect on the speed of the ball… In contrast to this, the person who goes straight back to the low point of his backswing has gained zero miles an hour as he starts to move into the ball. He must use a lot more muscular effort to gain sufficient racket speed in a short period of time.”

— Tennis 2000, by Bill Bruns and Vic Braden

Here is a side-by-side to emphasis the difference in racquet position of when the hips start to drive:

-

Use a larger swing:

“A large loop backswing also provides distance and time over which the racket can be accelerated.”

— Knudson, D. (1991). The tennis topspin forehand drive: Technique changes and critical elements. Strategies, 5(1), 19-22.

-

Improve the coordination of the body segments to increase the strength of the stretch-shortening cycle (SSC):

“If the backward and downward motion of the racket is timed to coincide with the initial forward motion of the proximal segments of the body, this increases the eccentric stretch of the muscles that may be used to accelerate the arm and racket.”

— Knudson, D., & Elliott, B. (2004). Biomechanics of tennis strokes. In Biomedical Engineering Principles in Sports (pp. 153-181). Boston, MA: Springer US.

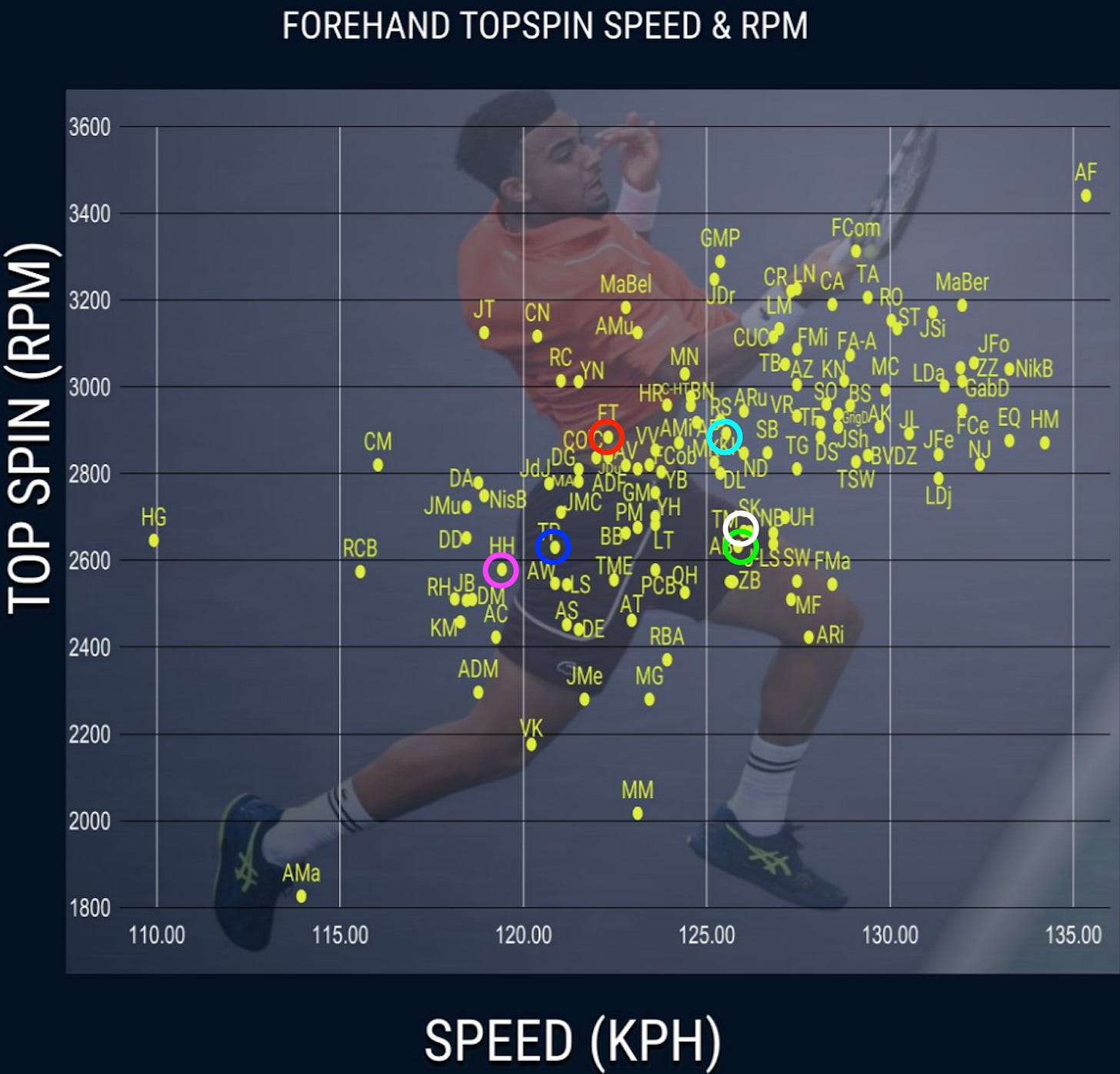

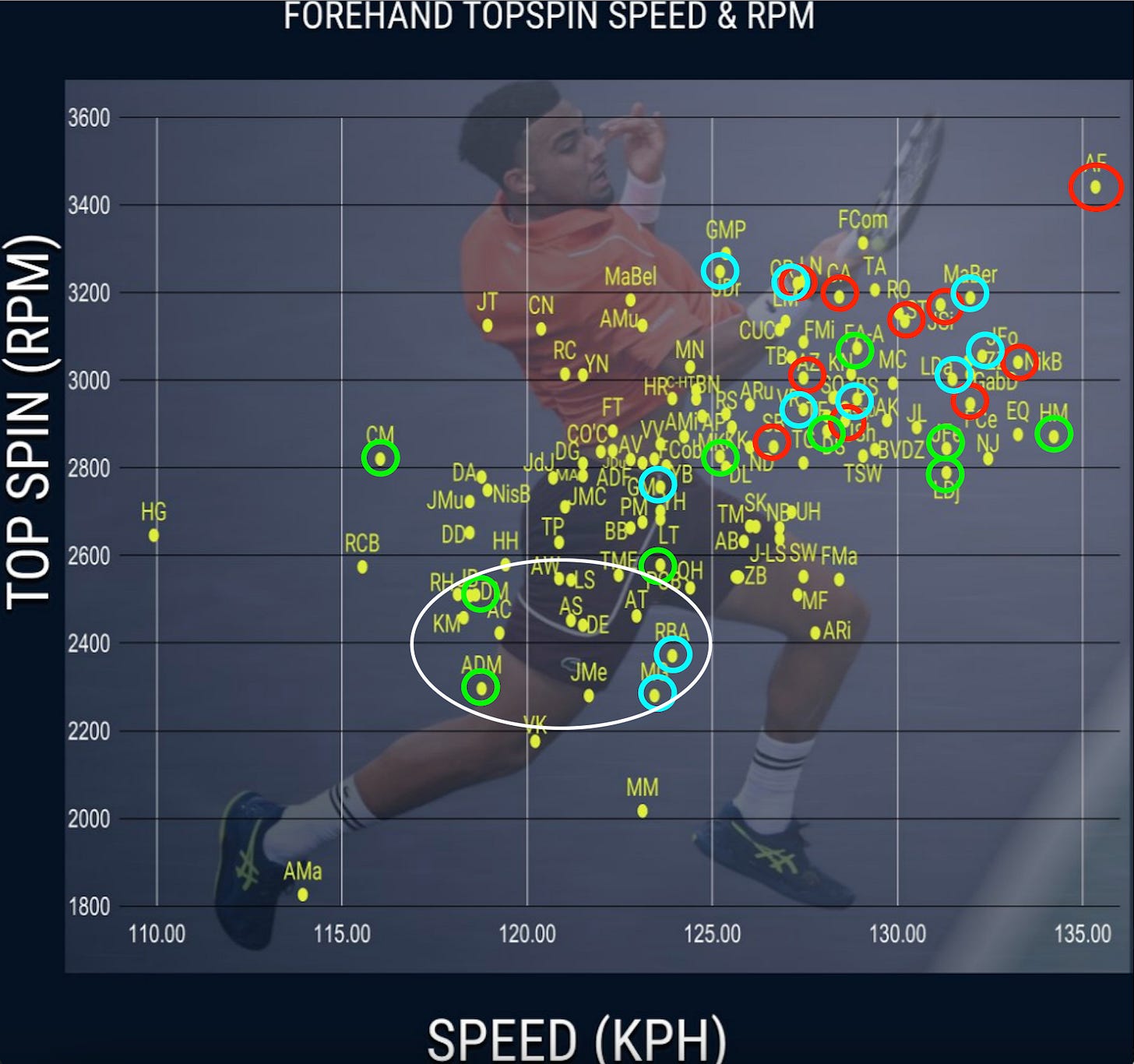

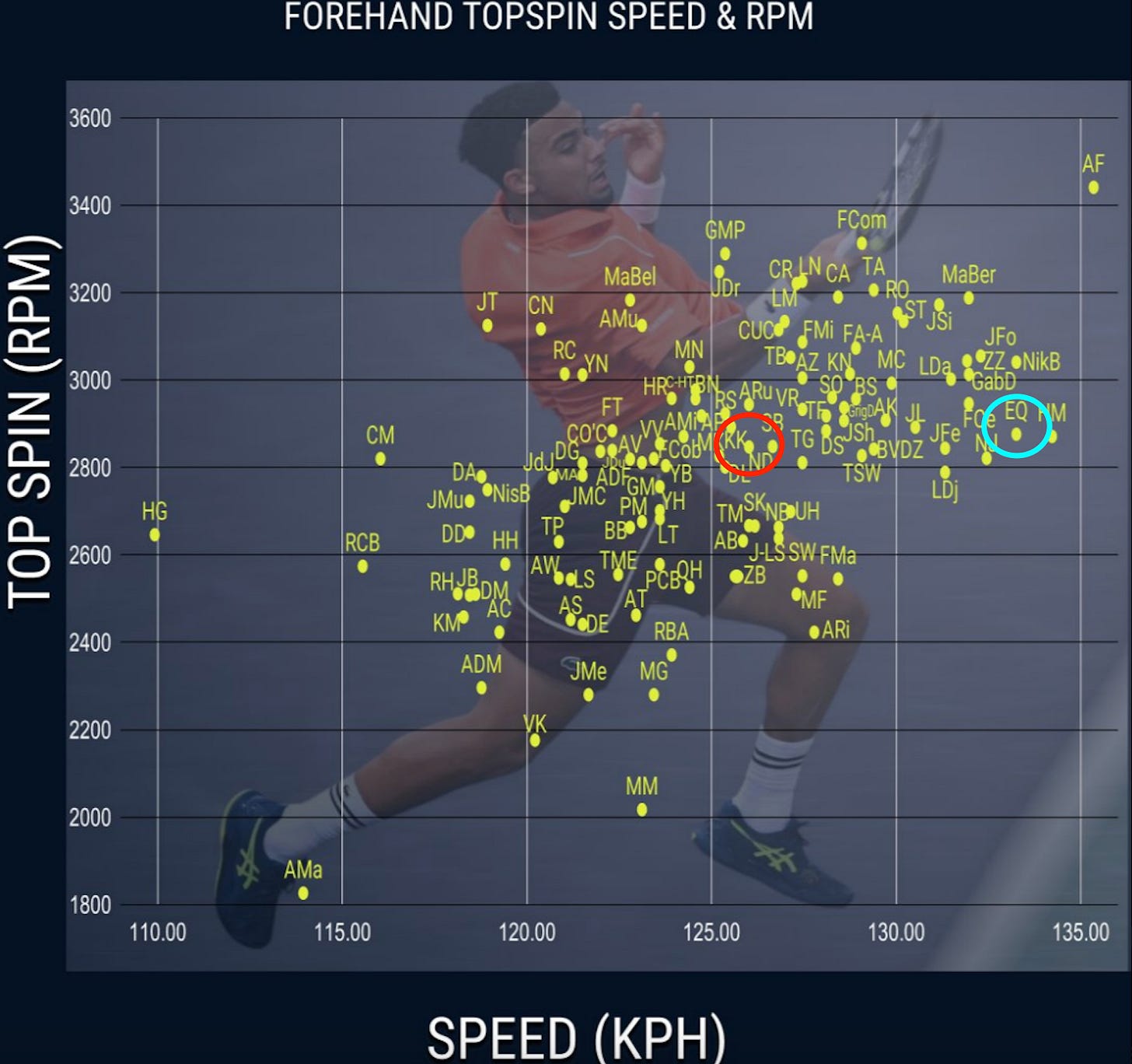

For the second year in a row, Arthur Fils has topped the Tennis Insights forehand speed and spin data:

Not surprisingly, he’s swingmaxxing:

In my original post I pondered if the nextgen swing might provide more racquet speed by virtue of a better SSC, as the wrist whipped from flexion to extension, and as the racquet moved from the outside to the inside. Maybe for some, but I now believe that these side-pointing flexed setups in more compact swings put players at risk of lacking strong speed and path outcomes due to late and weaker SSC’s.

If we rewind to the GIFs of Machac and Co., we can see their legs driving into the ground, hips and shoulders uncoiling with vigour, the elbow moving tremendously…it’s all textbook fundamentals in terms of using ground reaction forces and the kinetic chain to rotate the torso, and yet the racquet head remains remarkably still throughout. Players like Machac/Tiafoe/Hurkacz/Paul — due to the speed of today’s game — have eschewed the first two strategies of building racquet-head speed (gravity, larger swings), but crucially, they have failed to coordinate their racquet and body segments to the same degree as elite forehands. There is a lack of “backward and downward motion of the racquet” during their torso’s uncoiling:

This is compact to a fault, where the racquet head has a Falcon-esque talent for staying still (inertia will do that), despite the best intentions of the body.

In my last Mail Bag post I dropped a teaser of this piece with a GIF highlighting the difference in racquet flips between Hurkacz and Tsitsipas, despite almost identical setups in the unit turn. Here it is again slowed down:

Tsitsipas’ forehand is just as compact as Hurkacz’s in terms of the hand staying on the hitting side, but note how well the Greek’s racquet-head builds momentum in the exact opposite direction (“backward and downward”) of his torso and desired arm path (forward and upward). Tsitsipas has coordinated his torso and arm more effectively and is thus producing a much better SSC in the chest and arm muscles, as well as a longer angular path to contact from the moment of stretch.

“During stretching, when the rate of stretch is controlled, the muscles and tendons store energy (typically during a backswing). On reversing the movement during the shortening phase (the forward swing), the stretched muscles and tendons recoil and a portion of the stored energy is recovered. Science indicates that 10 to 20% of additional speed is achieved following a muscle pre-stretch.”

— Reid, M., Elliott, B., & Crespo, M. (Eds.). (2022). Tennis science: how player and racket work together. University of Chicago Press.

The question is, what specifically causes this difference in flip between Tsitsipas’ and Hurkacz’s swing?

What produces the deeper, stronger slot positions of Tsitsipas is a combination of greater shoulder external rotation and earlier forearm supination, occurring while the hitting arm is more horizontally extended. In english: Tsitsipas is going “palm up” earlier and more aggressively, when the hitting arm is farther back in space and not yet pulling forward, compared to players like Hurkacz. I’ve included images below to make this clearer.

To create that Sinner-side-pointing racquet tip in the initial unit turn that is something of a nextgen/ATP swing feature, you need to internally rotate the shoulder and pronate the forearm (palm down). In other words, you rotate your arm in the exact opposite direction of the slot position. And this is kind of what separates a “WTA” forehand from an “ATP” forehand:

And the reason players do the nextgen swing is to create more distance for the racquet tip and elbow to “flip”, in a bid to produce a better stretch of the hitting arm muscles, without the swing getting as large as a WTA forehand (by keeping the hand path lower/shorter, or “quieter”). The goal is to be compact and fast, kind of how fighter jets can launch off an aircraft carrier with the assistance of a catapult system.

And yet, we’ve seen that Paul et al. don’t flip the racquet very well. Compact? To a fault. Fast? Not so much.

Why?

I think wrist extension may play a role here. Or more accurately, the timing of wrist extension. Specifically as it relates to players who setup with flexion but don’t have extreme grips, where on contact they will require more wrist extension (Paul, Hurkacz).

I’ve touched on the gravity benefits of an extended wrist setup when using a Nextgen swing in the Sinner-Tiafoe Cincy final:

But beyond that, I believe pre-setting the wrist in a more extended position encourages earlier supination/external rotation.

If we do a little swing experiment with anything resembling a semi-western grip… if a player tries to supinate the forearm while the wrist is flexed, as the racquet flips, the strings open. This won’t work, so the player is forced to delay supination until the wrist extends, which happens passively in players like Paul and Hurkacz as the arm is pulled forward and while the torso is uncoiling.

This kills racquet-head speed, because delaying supination of the forearm weakens the racquet’s opposing “backward and downward” motion. If you weaken the backward motion, you’ll reduce the stretch, and that’s going to weaken the forward motion (i.e., internal rotation):

The upper arm internal rotation has been shown to be the main contributor to generate racket horizontal velocity in the flat and topspin drives (Takahashi et al., 1996; Elliot et al., 1997).”

— Genevois, C., Reid, M., Creveaux, T., & Rogowski, I. (2020). Kinematic differences in upper limb joints between flat and topspin forehand drives in competitive male tennis players. Sports biomechanics.

Weaker stretches, shorter paths; it’s like spinning the tires in a two-foot drag-race to contact. Emphasis mine:

“One of the central components in coordination is the linking of linear movements with angular or rotational motions through the entire body. While it is the velocity of the impact point (linear motion) that is ultimately critical for successful performance, this velocity will only be achieved by coordinating the rotations of a large number of body segments. This is particularly the case in linking the rotations of the trunk and hitting arm.”

— Reid, M., Elliott, B., & Crespo, M. (Eds.). (2022). Tennis science: how player and racket work together.

Syncing trunk and hitting arm rotations, and coordinating them with “backward and downward” racquet head movements. These are the keys of big modern forehands.

And if you do coordinate them well, then you can be more compact.

Here it is done exceptionally well by Fonseca:

It’s worth pointing out that even with an extended wrist in the setup, if the backswing is too compact — if “horizontal extension” is too little — you can’t swing in-to-out no matter how well you flip. Take a look at Henry Bernet’s opponent in last year’s Australian Open Boys Final. Ben Willwerth is a talented and fluid player, but his forehand backswing is so abbreviated it’s difficult for him to do anything other than hit flat redirects a la Mannarino:

Compare to Bernet’s longer, flexed-wrist Western cut:

To use our drag race analogy again: you can reach higher speeds on longer runways.

Maybe you watched Shintaro Mochizuki play Tsitsipas in their recent United Cup match? (or Australian Open first round). Same thing. Extreme compaction just squeezing the life out of speed and spin data:

Some readers often ask me about this or that player’s forehand, pointing to wrists and racquet positions alone, but that isn’t all that helpful. The swing has to be examined in its entirety and the coordination of body segments are major factors.

For example: let’s take a look at Ethan Quinn’s hammer of a forehand, which is as Nextgen-y as you can look in the setup, but the depth of slot position and right-to-left lag of the racquet head is elite given the size of his backswing:

If we compare this to another player with an almost identical setup, but far less teeth to his shot, we can see that Khachanov’s backswing length is more compact, and the slot position is “weaker” for lack of a better term. From last year’s Toronto Final recap:

Who’s going to generate more racquet head speed?

But some readers may be asking now (correctly): “wait, haven’t you been harping on about Alcaraz needing to get more compact on the forehand? Didn’t Thiem have hardcourt success when he shortened his swings? Aren’t these huge backswings rush-able?”

And you’re right. “Tennis is not golf”, as Karue Sell likes to say.

But it’s not Putt Putt either.

The biggest consideration that is often overlooked in tennis technique is the fact that within motor learning literature tennis is classified as an open-skill sport. Players must adapt their movement and shots to a myriad of unpredictable incoming ball trajectories and speeds, as well as opponent positions and tactics. In other words, after the serve (a closed-skill projection), tennis is just as much about reception as it is about projection.

And it’s because tennis is a game of reception, of being rushed for time, of being out of position, of being purposively thrown off balance, that swings become more compact when put to the grindstone of the ATP tour, sometimes shaved to a stumpy nub incapable of being a weapon in a speed and spin projecting sense, but not necessarily in a time-stealing, redirecting, consistently receptive sense (case in point: Khachanov made 85% of his forehands in 2025. Quinn? only 79%).

Every swing change is a tradeoff. Go uber-compact with a Western grip like Mannarino, and be left with a flat peashooter using teenaged tensions, yet comfortable hugging the baseline. Go higher and longer like a young Thiem (or Ethan Quinn) and get rushed on hard courts by aggressors, but possess nuclear power.

Herein lies the tradeoff that every player must decide upon.

And it’s true that Sinner and Alcaraz have created more compact forehands since their junior days. The backswings are lower, but they have always maintained violent “backward and downward” flips of the racquet, perfectly in sync with their torso’s unloading, and with enviable slot positions:

In the battle between reception and projection, the best forehands are still the best projectors in 2025, capable of deploying huge racquet head speed in service to speed and/or spin from all areas of the court. This is how you eliminate “neutral” balls, open the court with angles, attack low short slices, and clock 100mph forehands on the regular.

If we take Tennis Insights’ top-30 ranked forehands of 2025, we can see a trend: on average, the ten highest-rated forehands (red) are heavier (speed and spin) and more tightly grouped than the 11-20 forehands (cyan), which are heavier than the 21-30 forehands:

And if we look at the speed and spin laggards who are ranked highly (the white circle of Medvedev, de Minaur, Giron, and Bautista Agut), what do they all have in common? An eastern-ish grip. In other words, they can efficiently absorb and create protective depth and a lack of attackable height with slower, more compact swings because they can be more linear, rather than rotational:

In generalising the instruction of the forehand, there appear to be two general philosophies: a rotational approach to building racket speed and a more linear approach to building racket speed… The former approach emphasises the positive contribution of trunk rotation and shoulder internal rotation. It has been qualitatively observed that this emphasis tends to correspond with players using the western and semi-western grips. Conversely, the latter approach seems the preference of coaches that emphasise more eastern grips and the flattening the arc of the racket swing in the transverse plane near impact. Noteworthy is that neither approach precludes the rotation or contribution of key segments, rather they are emphasised in different ways and/or at different times.

— Reid, M., Elliott, B., & Crespo, M. (2013). Mechanics and learning practices associated with the tennis forehand: a review. Journal of sports science & medicine, 12(2), 225–231.

To summarise:

Given the speed of the game making longer and higher forehand setups prone to being rushed, players are adopting lower and more compact setups (“nextgen” swings), eschewing 90s/early 2000s motions that used larger swings and gravity. However, this places a premium on the “backward and downward” racquet motion being well-coordinated with the body uncoiling to provide racquet head speed and in-to-out paths necessary for more extreme grips. In my viewing, wrist extension seems to play a role in facilitating that SSC through a better backward and downward flip of the racquet, and wrist flexion can inhibit it, but each player is unique in their physical properties and ability to coordinate the arm and torso, and must be judged on their own merits. Perhaps that coordination chain is part of what “talent” is. People talk of players looking “elastic” and of forehands looking “whippy” and “wristy” (Federer, Sinner), despite the wrist being quieter in these instances; it is their ability to time the palm up movement with the torso that creates a stretch that whips the racquet. I believe fewer moving parts is helpful for timing, but above all the modern game demands an efficient stretch.

“Energy efficiency is the absolute criterion”.

This guy has been more efficient than anyone. How else to hit this at 38?

Footnotes: