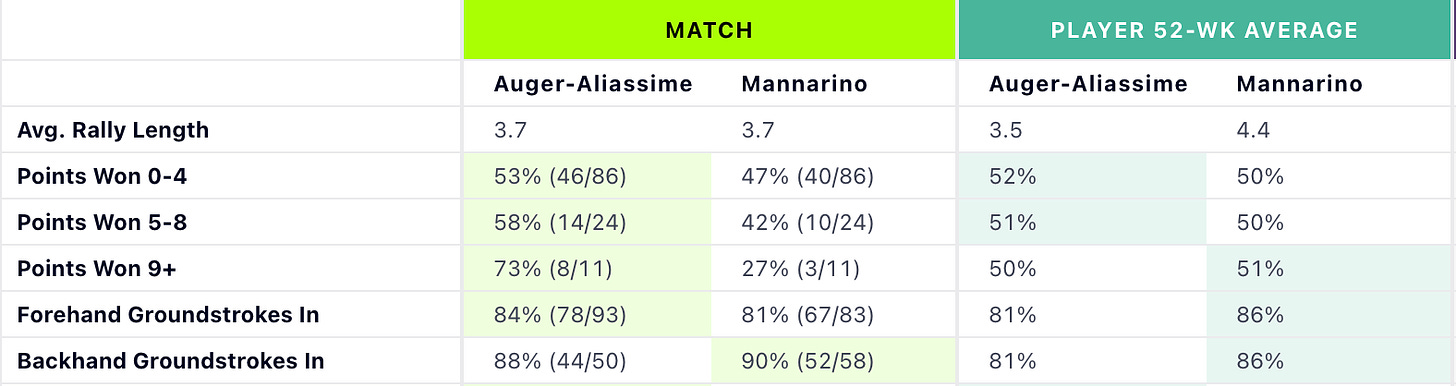

Felix Auger Aliassime defeated Adrian Mannarino 6/3 7/6 to defend his Montpellier ATP 250 title on Sunday. It’s the Canadian’s 9th title of his career (eight indoors), and he moved up two spots to 6th in the rankings.

When FAA started his ranking surge ~US Open last year, at the core of that was his usual serve and forehand excellence. But as I noted in the Sinner loss at the Paris Masters, FAA’s backhand had silently become a steadier shot that directs more traffic into his forehand:

… in recent months FAA is hitting the backhand less often, changing down the line more often, and making fewer unforced errors. All those things are great for the FAA game. Being able to go line gets Felix out of his weaker backhand crosscourt pattern, and opens up forehand patterns that allow him to dominate opponents. Doing all that while missing less is the dream

Montpellier was even better: 81% backhands in, but the speed was up to 71 mph, averaging 3.3 winners and 6.5 unforced errors, and was only used 38% of the time.

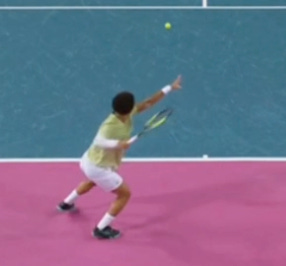

He started Sunday’s final with similar trends, mincing his first backhand return of the match, before threading this to open up 0-30 on his way to breaking to love:

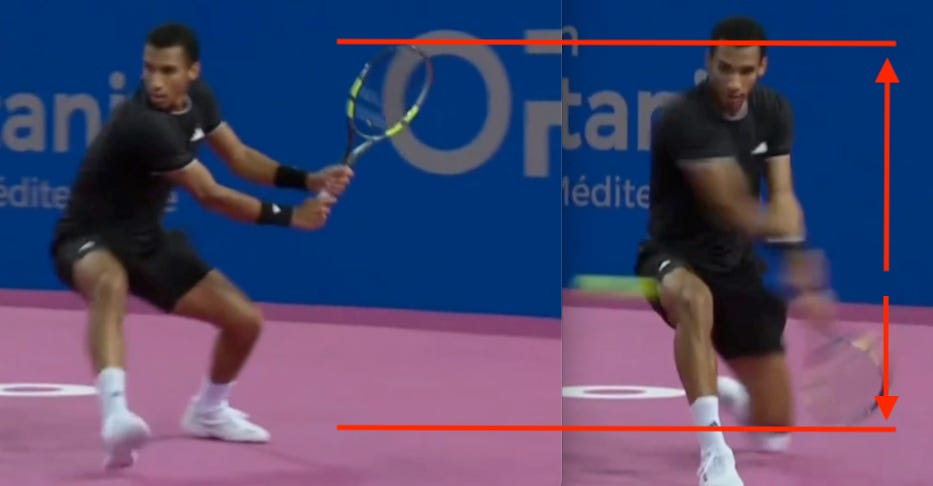

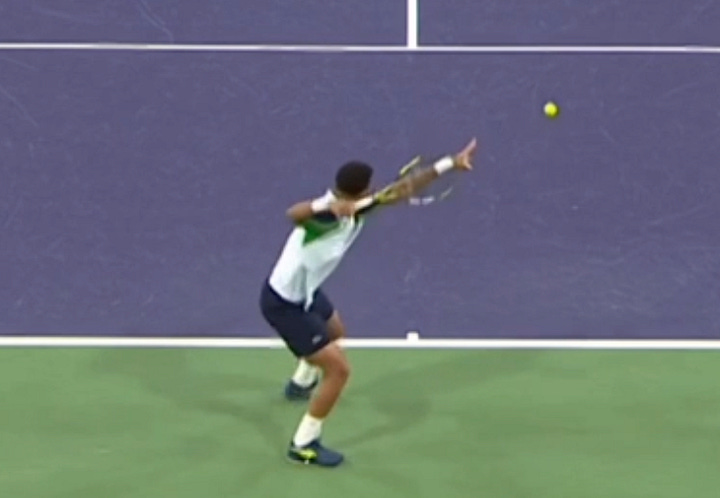

As a lefty, the play is pretty simple against FAA: use your natural forehand crosscourt to pressure the FAA backhand, where the large amplitude of his backswing in terms of high-to-low can sometimes become a timing issue:

Compare to Mannarino’s pancaked swing, where the racquet head doesn’t drop beneath the hands at all:

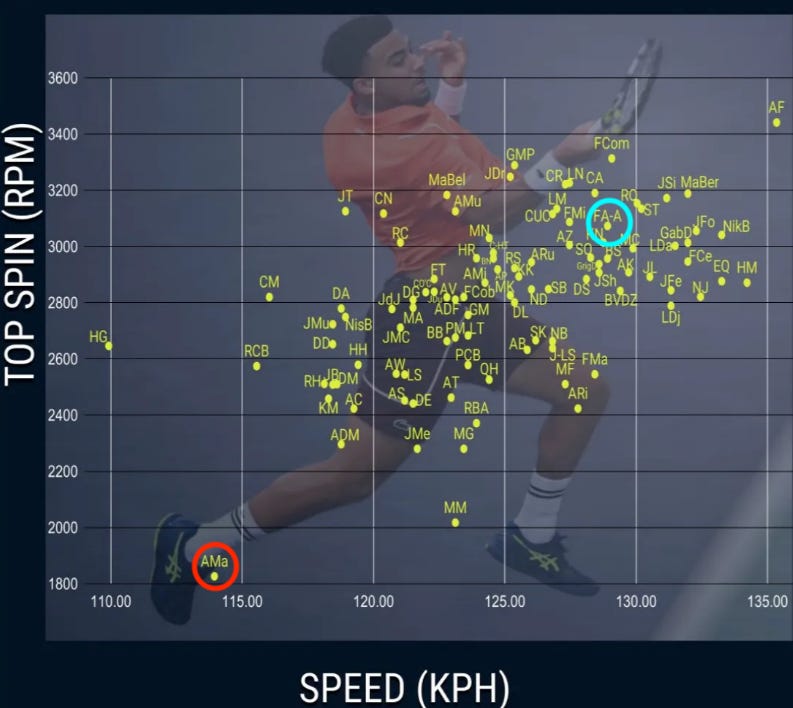

But going back to the lefty game plan, the problem for Mannarino is that he possesses one of the off-the-map softest forehands on tour; he’d rather trade speed than produce it.

As a result, FAA had the time to step in and redirect backhands all match:

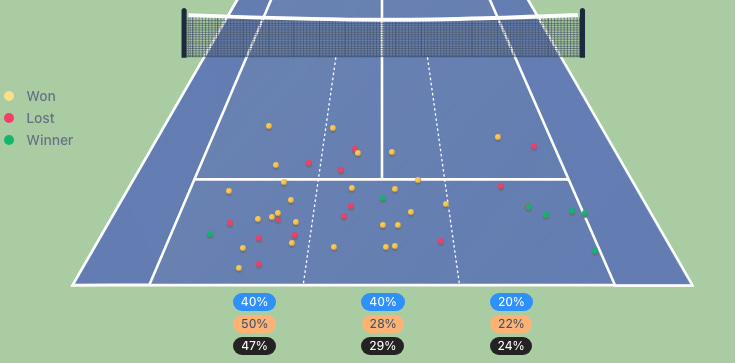

It also meant FAA could play more middle, knowing the slow and flat Mannarino ball would struggle to create from the middle, and that’s exactly what FAA did, playing 40% of his backhands through the middle corridor:

Of course, Mannarino doesn’t have the same luxury. Middle to FAA nearly always means a forehand, and the Canadian owns one of the heaviest in the game:

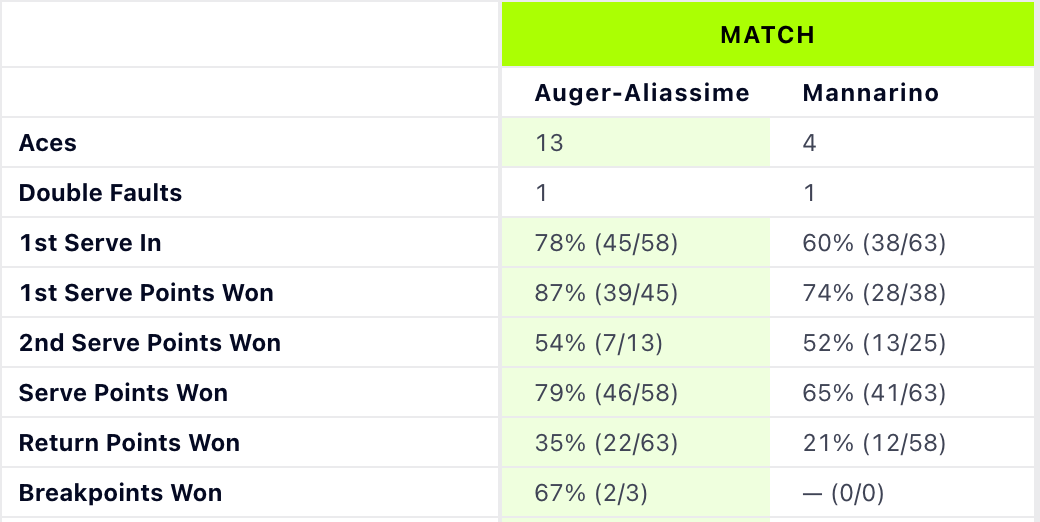

But of course, on a fast indoor hard court, it was always going to be the serve +1 that carried a player over the finish line this week. FAA’s was impeccable: 47% of first-serves unreturned, and finding a forehand after his serve 69% of the time, winning 71% of those +1 points. Those numbers means he never faced a break point:

Mannarino survived a match point on his serve at 4-5 30-40, and found himself up 4-2 in the tie-breaker, riding the wave of French support as he found some rhythm and range off the ground. It was one of the longest points of the match at 12 shots, and Thread of Order readers will appreciate that low defensive slice backhand from FAA, sinking it below the net for the two-shot pass:

That point would prove to be a dagger, as FAA reeled off the last five points to take the tie-breaker 7-4. The last couple of points were both quite long — 19 shots at 5-4, and 8 shots at 6-4 — and it was the Canadian coming out on top, wrestling control with his heavy forehand:

FAA dominated the 9+ rally category:

“Adrian is always a very tough opponent to play, for all players, I think,” said Auger-Aliassime in his on-court interview. “That’s why myself and all our peers on Tour have so much respect for him and the challenge he poses on the court. I knew it was going to be a tough match today, so I’m very happy. It’s amazing emotions to win again here. I’m thrilled with my whole week and especially today.”

— FAA for atptour.com

Other observations from this week:

Arthur Fils made his long-awaited return from a back stress-fracture at the Montpellier 250. While the Frenchman admitted that he doesn’t watch much tennis, he seems to have at least picked up on, and mimicked, the benefits that Carlos Alcaraz found when lowering the hitting elbow on the forehand. In the three matches Fils played in Montpellier the elbow was quieter:

The hitting elbow stays lower now (at or below the shoulder level), whereas Fils often used to lift tremendously high when given time to attack mid-court balls:

No matter the ball, he’s shaved that forehand prep during his injury layoff, but he’s still got that dangerously good slot position.

The old prep:

Fils takes on Alex de Minaur in a blockbuster round one in Rotterdamn. Bullish players who continue to adapt with the best. A quote from Alcaraz vs Fritz in Tokyo:

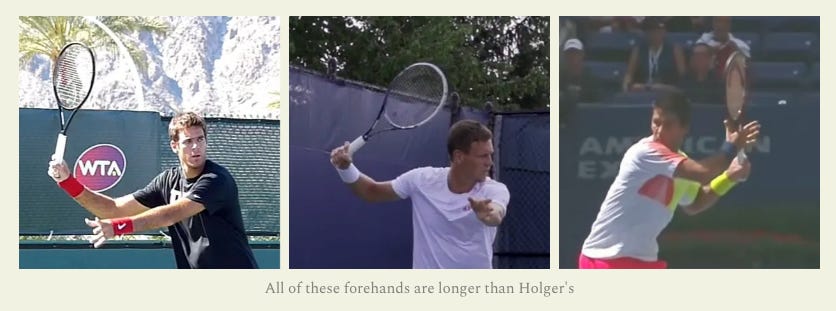

Given so many points are in the 1-4 shot category, and that these shots are necessarily: (a) against very fast incoming serves as the receiver; or (b) played inside or on the baseline as the server for the ‘+1’ shot; and (c) on a hard court that is likely to be medium-fast, it’s paramount to adopt a forehand motion that can handle speed and a lack of prep time if you are wanting to play an aggressive brand of tennis in 2025.

Holger Rune has also been debuting a new forehand prep, albeit on the Instagram circuit still, as he continues his recovery from an achilles tear. I’ve been critical of the Dane’s forehand before, noting that it was almost too compact for the modern game. I mused on possible solutions after last year’s Australian Open:

The question is what to do about it? I think there are multiple solutions. I mean, he’s leaving speed on the table in numerous areas. He could keep the left hand on the throat for longer like Sinner and Alcaraz to coil the torso more, he could lift the hitting elbow higher and invert the racquet without adding the left hand like Berdych, he could flex the elbow more in the setup like Verdasco, or he could simply have a higher takeback but keep the racquet tip up like del Potro. All these solutions add a little more length and would help provide more and smoother racquet speed.

Rune has added a longer left-hand hold on the unit turn, and the Berdych-esque higher elbow lift:

Along with a new forehand, Rune is rumoured to be training with Wilson’s new Python prototype (Khachanov, Korda, Tsitsipas), which has been made to directly compete with the incredibly popular Babolat Aero 98 (Alcaraz, Fils, Rune, Bublik).

Remember the name (and where to put the accents). Kouamé is a 16-year-old Frenchman (boy?) who made headlines for qualifying in Montpellier. He took the first set against last year’s finalist, Alex Kovacevic, to make good on his splash. First impressions leave one pretty excited: there’s a fluidity to his already-impressive athleticism, and like so many youngsters today, a natural blending of modern sliding with forecourt steals:

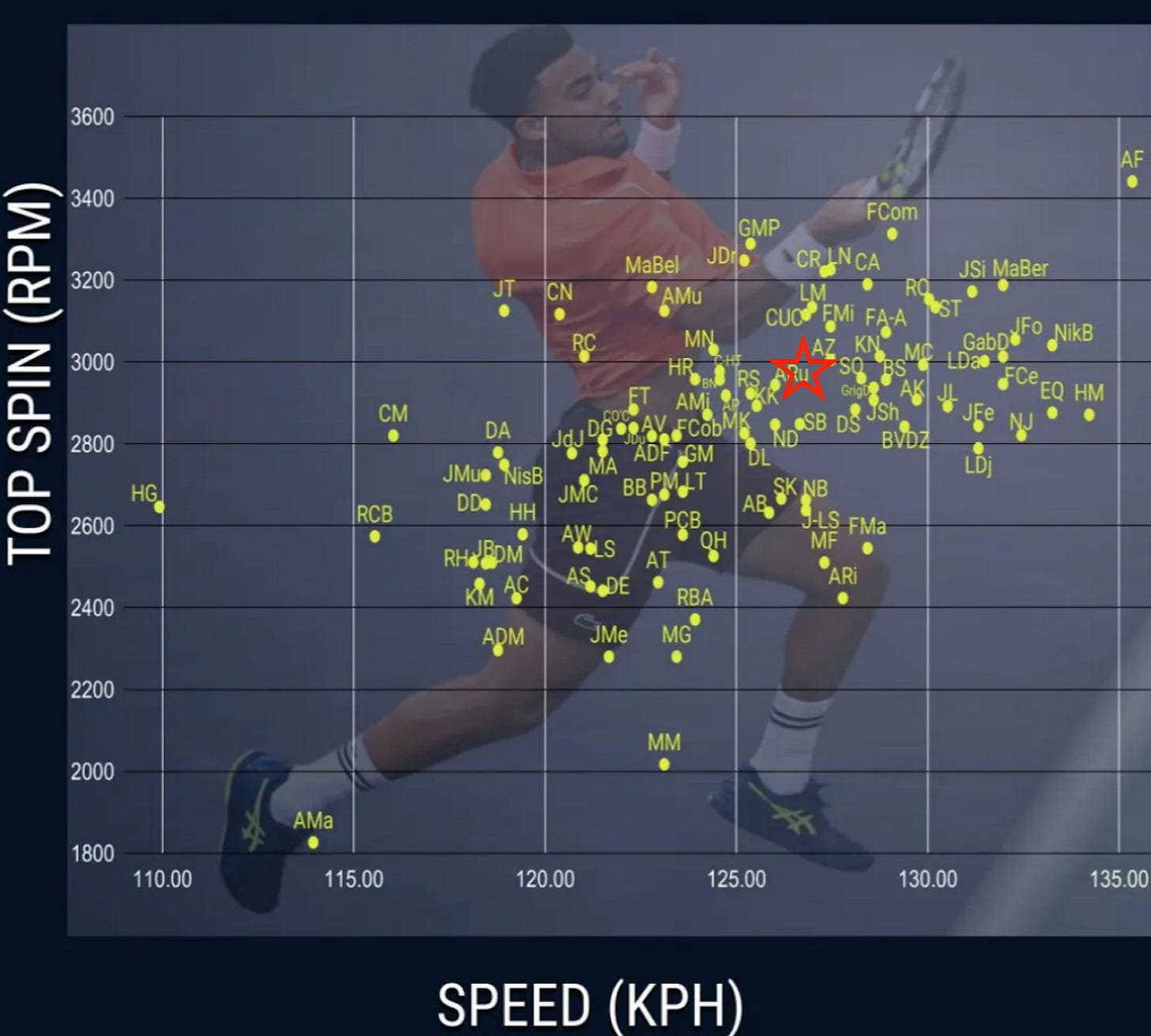

The serve got up to 136 mph (219 kph), and the forehand averaged 127 kph and 2996 rpm. That would put Kouamé nestled right between a Rublev and Zverev:

If I was to be critical of the forehand, perhaps the slot position is a little weak for this to become a generationally good shot. It’s a little too compact, if you know what I mean. I don’t think this swing, despite all that talent, could venture farther up-and-right on the forehand chart:

But at just 16, this is a super-exciting prospect to bookmark and keep an eye on. Richard Gasquet was with him as coach in Montpellier, and he knows a thing or two about being a prodigy with expectations.

Well that’s all I got. I’ll see you after Dallas and B.A.