When I wrote about the Rene Herse components that are the lightest of their kind, I was reminded of a reader who once asked: “Why are you so focused on saving a gram here or there? For the 99.999% of us who are not professionally racing, but just wanting to get out there and ride, shouldn’t the focus be on function and longevity?”

Of course, the reader is right: Function is always more important than light weight—even for pro racers. A lightweight part that doesn’t work isn’t much good. To win a race, you first have to finish. And for those of us who can’t and don’t want to replace our components every season, longevity is more important than saving a few grams. We’re all in agreement here. But do we really have to choose? Or can we have light weight and function and longevity?

That depends on how the light weight is achieved. I first learned about that from Richard Sachs. Way back, he was supporting a small team of cyclocross racers. Their frames were made from ultra-light, thinwall tubing, yet they seemed to last as long as other frames, despite the hard use they saw. Frames fail at or near the joints, and thinwall tubes dissipate stresses better, whereas thicker, stiffer tubes concentrate the stresses at the joints. Hence a well-built frame made from high-quality thinwall tubes is no less durable—and potentially more durable—than a heavier frame made from thicker tubing.

Another influence was the German journalist and engineer Christian Smolik, whose classic book ‘Fahrrad Tuning’ showed how to modify components to make them lighter and stronger. Smolik also showed examples of poor lightweighting—things like drilling holes into brake calipers. He pointed out that there’s a difference between ‘stupid light’ and ‘smart light’:

‘Stupid light’ means taking a conventional bike part and making it lighter and lighter until it breaks. Then you add back a little material and hope it’s enough to make it work reliably—at least until the finish line of your race.

‘Smart light’ happens when you optimize a component and fine-tune the design until you have the right amount, of the right materials, in the right places. That means your component will inevitably be light—in fact, it’ll probably be lighter than the ‘stupid light’ component that doesn’t change the overall design and just replaces materials with lighter ones.

Let’s look at some examples of ‘smart light’ and ‘stupid light.’

Design: ‘Smart Light’

Butted spokes are a good example of components that are lighter and stronger. Double-butted spokes are thinner in the middle than at the ends. Less material means they are lighter. And because they are thinner, they are also more aero.

What may surprise many is that butted spokes are also stronger than ‘beefy’ unbutted spokes. Here’s why: Spokes fatigue when they get de-tensioned as the wheel compresses at the bottom, where the tire touches the road and pushes the wheel upward. Each time the wheel turns, every spoke goes through one cycle of de-tensioning and re-tensioning. After many, many cycles, the spoke will break.

With the same spoke tension, thinner spokes stretch more, so they lose less tension as the wheel compresses. This means that thinner spokes fatigue much less.

If spokes fail, they break at the ends, and that’s where double-butted spokes have the same amount of material as thick straight-gauge spokes. That makes double-butted spokes a ‘win-win’ idea: The ends are as thick and strong as straight spokes, while the middle is thin to reduce fatigue. The only down side of butted spokes is that they wind up more as you tension the wheel, so they require more skill from the wheelbuilder. Well, and they are more expensive, but the (small) extra cost is well worth it, when your wheels will last much, much longer.

Design: ‘Stupid Light’

When 650B wheels first became popular in the U.S., there were only two supple tires in the new wheel size. One was 32 mm wide, the other 42 mm. Clearly, there was a need for an in-between tire. A small company jumped into the fray, with a 38 mm tire that was ultralight, weighing just 300 grams.

How did they achieve the light weight? They simply made the tread as thin as possible. The casing was coated with just 1.3 mm of rubber. Rubber is heavy, so that saved a lot of weight. It also had an obvious drawback: There was no extra rubber to wear. Riders jokingly referred to these tires as ‘pre-worn.’ After 800-1,000 miles (1,500 km), the tires were threadbare.

Design: ‘Smart Light’

At Rene Herse Cycles, we don’t duplicate products that already exist, but the ‘superlight’ 650B x 38 mm tires weren’t really practical. When we developed our Rene Herse tires, we decided to make a 650B x 38 tire with a better service life.

With all our smooth tires, we add extra rubber on the center of the tread to increase their longevity. Our 38 mm tires last on average 4,000 to 5,000 miles (7,000 to 8,000 km)—about five (!) times as long as the ultra-light model available previously. Those few grams of rubber—visible in the cross-sections above if you look closely—don’t affect the rolling resistance, and the weight penalty is small.

We developed our Extralight casing that improves performance and comfort, while also saving some weight. The end result is a tire that is (almost) as light as those ‘pre-worn’ tires, but is a more reliable and economical choice.

Materials: ‘Stupid Light’

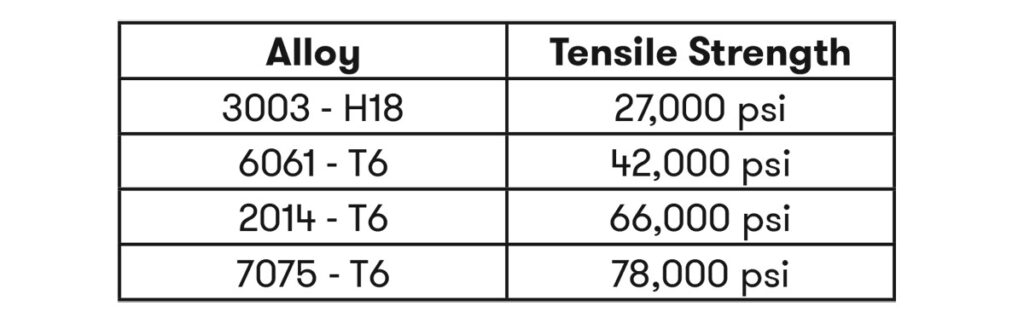

Choosing the wrong material is another way to create ‘stupid light’ components. In the 1970s, an Italian company offered a handlebar that weighed just 240 grams—lighter than any other aluminum bars. (This was before carbon handlebars became widely available.) The secret: The ‘Superleggero’ bars were made from 7075 aluminum.

Another Italian company made superlight ‘Ergal’ rims that were also made from 7075 aluminum. (‘Ergal’ is another name for 7075 aluminum.)

Looking at the table, 7075 aluminum looks like the perfect material for highly-stressed bicycle components: It’s stronger than other alloys. However, the table above doesn’t show two serious problems:

- Once it’s heat-treated, 7075 aluminum does not bend, but it suddenly breaks if it’s flexed too far. That was an issue with the ‘Ergal’ rims: They were very strong, but really big impacts tended to shatter, rather than bend, them.

- 7075 aluminum suffers from ‘stress corrosion cracking’: If the part is flexed while exposed to moisture, tiny cracks open that let the moisture penetrate deep into the material. If the exposure continues, the cracks grow quickly. That’s an issue with handlebars: If the rider’s salty sweat penetrates the bar tape, it’ll cause corrosion cracking of the bars. And once the bars are weakened, they won’t bend, but suddenly snap.

However, not all bike parts made from 7075 aluminum suffer from failures. The ‘Superleggero’ bars above seem to have worked fine, at least in races on smooth roads. When the company pushed the technology further and introduced a 220 g bar, reports of failures became more common.

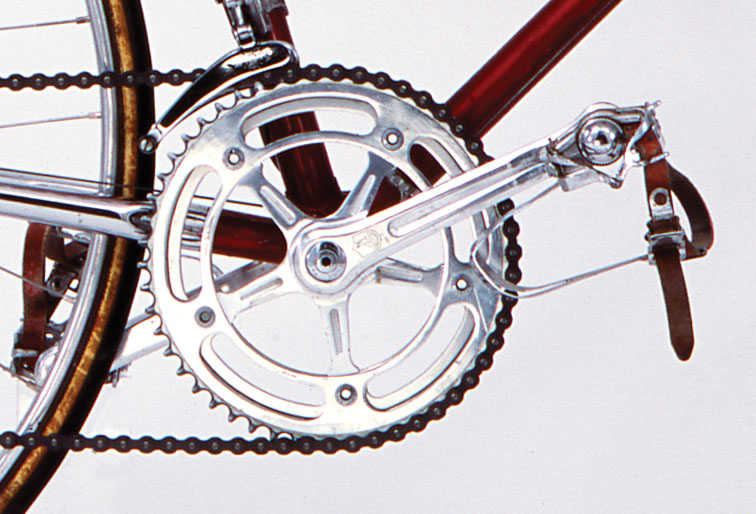

A few decades earlier, Campagnolo apparently used 7075 aluminum for their first cranks. The very first iteration had a square-ish cross section and worked fine. In 1961, Campagnolo changed the design to reduce the Q-factor, making the arms thinner (above). Even though the new arms were wider and used the same amount of aluminum, the less-square cross section was less strong in torsion. The result: Multiple cranks broke in the 1962 Tour de France. At the time, the failures were attributed an alloy that was ‘too dry’ as well as to the new shape. Apparently, the company then switched to 2014 aluminum for their crankarms—as mentioned in a 1970s Campagnolo ad.

Today, some companies again make their crankarms from 7075 aluminum. Why? The heat treatment of 2014 aluminum can be difficult to master. And if the heat treatment isn’t perfect, the strength of the alloy is much reduced. That’s why many suppliers don’t like to work with 2014 and prefer 7075 aluminum that’s easier to heat treat.

A friend bought a crank from a small company, made from 7075 aluminum. After riding it for 6 months—through one Colorado winter—he noticed many small rust-like pits on the surface of the arms. He sent the cranks to us so we could have a look. When we tried to sand out the cracks—standard practice to eliminate stress risers that can cause the cranks to break—we found that the cracks went deep into the metal.

Cranks are both constantly flexed and also exposed to spray on wet roads, so they are especially susceptible to stress corrosion cracking. Winter in Colorado is probably the worst-case scenario… Still, it was sobering to see how deep the cracks went after just 6 months of use. There was no way to salvage these cranks, and they were retired.

Here’s what we’ve learned from these examples. Rene Herse components take a clean-sheet approach to making components, so their light weight contributes to their performance (both speed and comfort) and their long-term durability.

Materials: ‘Smart Light’

Lightweight handlebars have advantages that go beyond their weight: The thin material flexes more and absorbs shocks better. The difference is noticeable, especially on long rides and/or rough terrain.

How to make light bars that are reliable? Even though it looks less strong on paper, 6061 aluminum is a better material for handlebars. Heat-treating the material adds strength—that’s the ‘T6’ after the alloy—which allows using thin walls for our Rene Herse bars. Not as thin as those old ‘Superleggeros,’ but 25 grams are a small price to pay for a bar that bends in a fall rather than shatters, and that isn’t susceptible to stress corrosion cracking. Especially since today’s handlebars are ridden and raced, not just on smooth roads, but also on gravel.

With cranks, 2014 aluminum—chosen by Campagnolo after their early cranks cracked—is still the best material for crankarms today. If road and gravel crankarms fail, it’s due to fatigue, not overloading due to impacts. Resistance to stress corrosion cracking is far more important than ultimate strength. We found a supplier who has mastered the heat treatment. (We check cranks from each batch to make sure…)

For the chainrings, 7075 aluminum is the material of choice. It’s harder and far more wear-resistant. Unlike crankarms, chainrings aren’t subjected to much flexing, so stress corrosion cracking isn’t an issue. The only concern with 7075 chainrings: They can’t be trued by bending them like 6061 chainrings, so they have to be manufactured to very tight tolerances. At that point, the resistance to bending becomes a plus: If your bike falls over, the chainrings won’t bend, but spring back after the impact.

The correct material choice, together with net-shape forging of the arms—rather than machining the arms to their final shape—enables Rene Herse cranks to pass the most stringent EN ‘Racing Bike’ standard for fatigue resistance, despite their light weight and slender shape. And thanks to the smart design—with just three arms where most cranks use four or five—they are also superlight.

We also offer titanium crank bolts that replace the steel bolts. Isn’t that ‘stupid light’? Not in this case: Beefy steel bolts are needed to seat the cranks on the square taper. Once the cranks are tight, holding them in place requires much less force. Tighten your cranks with our steel bolts first. Then replace the steel bolts with our ti bolts.

We use the strongest titanium for our bolts. In a pinch, so you could use them to tighten the crankarms, but we don’t recommend this.

How ‘Smart Light’ also improves function and longevity

In the opening paragraph, I wrote that light weight, done right, also improves function and longevity. A good example are our Rene Herse centerpull brakes.

Each Rene Herse centerpull brakes weighs 137 g and clears 42 mm tires with fenders. That’s less than top-of-the-line rim brakes for race bikes that clear 28 mm tires. How can we get so much clearance without extra weight?

We mount the brakes directly to the fork blades and seatstays. Direct-mount brakes are lighter, since they don’t need an extra piece connecting the pivots. Mounting the pivots directly to the frame eliminates flex in the connecting piece and in the center bolt. That makes the brake more powerful, in addition to saving weight. Less flex also means better modulation, since the angle of the brake pads doesn’t change as they squeeze the rim harder.

The shape of the arms is optimized using Finite Element Analysis, to put material only where it’s needed. Removing unnecessary materials saves weight. It also makes the arms stronger, since they are loaded uniformly across their entire length, without stress concentrations.

Less weight, more power, better modulation—all these positives go hand-in-hand. It’s like the butted spokes: Making them stronger and more powerful also makes them lighter.

For a long time, we were the only ones advocating for direct-mount brakes—until Shimano introduced direct-mount brakes in 2013. Once again, we were just a bit ahead of the rest of the bike industry.

All this applies to our cantilever brakes, too. The same features that make them so powerful also make them so light.

For our brakes, we also offer titanium bolts—but only where it makes sense. The eyebolts for the brake pads are big because they need a hole for the post of the pad, not because the stresses are super-high. So we make the eyebolts out of titanium—they are still more than strong enough.

The lower bolts attach the brake to the pivots. Those are made from steel to avoid any risk. Since they are short—they thread directly into the frame, rather than having to go through the bridge (rear) or fork crown (front)—the steel mounting bolts are so light that titanium wouldn’t save significant weight.

The titanium bolts (where they make sense) exist for a reason: A light bike feels different from a heavy one. And a light bike isn’t the result of one or two superlight parts, but of shaving 20 or 50 grams from every component. It all adds up—and you can really feel the difference when you ride. When you climb out of the saddle or when you lean the bike into a corner during a mountain descent, a light bike reacts differently from a heavy bike. And that is independent of how much the rider weighs.

Even for those of us who don’t care about racing or even about speed, a lightweight bike is more fun. And if the same things that make your bike lighter also improve function and longevity, what’s not to like?