I wrote last week about the decline of specialization on the men’s tour. I proposed that we see more good all-around players because, as the overall level improves, there’s less relative value in being a one-dimensional servebot or dirtball grinder.

A few people responded–and I paraphrase, slightly: It’s the surfaces, stupid.

Everybody seems to agree that at some point, let’s say between peak Sampras and peak Djokovic, surface speeds converged. Hard courts got slower, and some grass courts got slower, too. Serve-and-volleying mostly disappeared, and grinding baseline play took over.

The only debate, it seems, is why. Was it a conspiracy to give the fans (well, all the fans except for the ones complaining) what they wanted? Is it the balls? The rackets? The strings?

I’ve always been skeptical of the conspiracy theory. More generally, I have been–and still am–skeptical that playing conditions have changed that much. Just because everybody believes something–even if those people are top-ranked players and well-respected pundits–doesn’t make it true. The historical record shows that styles have changed, but it’s much harder to marshal evidence that the surfaces themselves are meaningfully different than they were 20 or 30 years ago.

A quick review

I’ve looked at this stuff before. Here’s a quick summary:

- The Mirage of Surface Speed Convergence (2013): I compared ace rates and break rates on hard and clay courts for pairs of players, 1991-2012. I found that the difference between hard courts and clay courts had, if anything, slightly widened, even though the conventional wisdom of convergence was fully in place by then.

- The Grass is Slowing: Another Look at Surface Speed Convergence (2016): I wish I had named this differently, because I didn’t show that the grass slowed, I showed that rally lengths at Wimbledon (and to some extent at the hard-court slams) were converging with those at Roland Garros. It was my first stab at the problem using Match Charting Project data, which meant it used rally length, instead of ace and break rates. However, it relied on limited data, which meant there were heavy biases in which players it measured.

- Surface Speed Convergence Revisited (2023): With more MCP data, I worked out a simple model of how much surface affected rally length, and how the effect had changed over time. Now without the selection bias, I showed that in both men’s and women’s tennis, the influence of surface on rally length had shrunk.

Pick your stat

To grossly oversimplify: If you look at ace rate, there’s no evidence of surface convergence. If you look at rally length, there is.

I didn’t want to rely on a 2013 mini-study for the ace-rate conclusion, so I came up with some new fodder.

My surface-speed ratings are based entirely on ace rate. Originally, this is because we don’t have better stats going very far back, while we do have ace rate for all ATP matches since 1991. The MCP has an increasing amount of coverage, but it is not complete, and the ace-based ratings have always seemed to capture surface-speed differences pretty well. There’s some noise, because there are only so many matches per tournament per year. But in general, they give us a pretty good idea of what’s going on.

The downside is that they are indexed to each year’s average. The rating for the 1991 edition of Wimbledon is 1.20, meaning that–controlling for the mix of players–there were 20% more aces than a 1991-average event. This year, Wimbledon’s rating was 1.12: 12% more aces than the 2025 average. But are those averages the same?

That question offers us a neat little experiment. Instead of indexing on a single-year average, why not do two years at a time? The pool of players was almost identical in 1992 as in 1991, so it’s a fair comparison. As it turns out, Wimbledon’s ace-based surface rating went down from 1.20 to 1.06 between 1991 and 1992. That kind of shift often happens due to randomness, but maybe it could be validated by a longer trend. Looking at two years at a time–1991 and 1992 together, 1992 and 1993 together, up to 2024 and 2025 together–allows us to make the same comparisons for the entire tour calendar, for a span of 35 years.

Well, in that span, ace rate has gone up quite a bit. And not just because mediocre servers have been replaced by better ones. On average, the same servers (against the same returners, though the returner effect is much smaller) have upped their ace rate about 2% every year. Not enough to notice as it happens, but enough to move the ATP tour average ace rate from below 7% in 1991 to a bit over 10% today. Some of the difference is due to the tournament mix–a shorter clay calendar, mostly. But I ran the same analysis on a core group of 15 events that have been in the same place since 1991, and the controlled-for-players increase is still 1.6% per year.

What about convergence, taken literally? Have faster events gotten slower, while slower events have sped up?

Nope! The variance between tournament ratings is almost exactly the same in 2024-25 as it was in 1991-92. An example: Back then, Wimbledon’s two-year average was 1.13, while Monte Carlo was 0.58. Over the last two years, Wimbledon’s rating has been 1.14, with Monte Carlo at 0.57.

It’s the strings…

How do we reconcile the evidence that ace rate has gone steadily up, while rally length has also increased?

Setting aside laboratory-type measurements (like CPI/CPR, which we don’t have far enough back, anyway), the purest way to measure court speed is ace rate. A slow court keeps the ball on the ground longer and slows down the rest of its trajectory. Returning is all about reaction time, and ace rate tells us whether returners physically got there or not. That’s why there are, reliably, so many more aces on hard and grass courts than on clay, and on faster hard courts than slower hard courts.

Now, it could be that players have gotten stronger, serve tactics have gotten less predictable, and racket/string technology allows servers to put the ball in the corner more often. All of that is probably true, so the 2%-per-year average likely overstates the change in surface. The ace increase might entirely be attributable to training and tech. But if you want to argue that surfaces have gotten slower, you’ve got an uphill battle to explain how aces have gone so far in the wrong direction.

The rally-length trend is easier to explain. Unlike ace rate, shots-per-point isn’t just about how the ball interacts with the surface. It’s about tactics and spin.

And actually, tactics are themselves largely about spin. And spin, well, that brings us to polyester strings.

Modern topspin is possible largely thanks to polyester strings. The best-known milestone is Gustavo Kuerten’s 1997 French Open title, the first major won with a Luxilon-strung racket. It took a few years for everybody to make the switch, but polyester string was kryptonite for serve-and-volleying. Now it was possible to hit returns that dipped to the server’s feet at the net. All that topspin also made it tougher to move forward. More topspin meant that deep groundstrokes were higher-percentage shots, and that opponents needed to give up even more ground to comfortably handle them.

When I wrote about Lleyton Hewitt a few years ago, I showed how Hewitt forced Roger Federer to basically give up serve-and-volleying. That was 2002-05. If it hadn’t been Hewitt, it would’ve been someone else–or everybody else.

Less serve-and-volleying, safer groundstrokes, fewer net approaches overall … all that adds up to longer rallies. No surface change necessary.

… and the youth

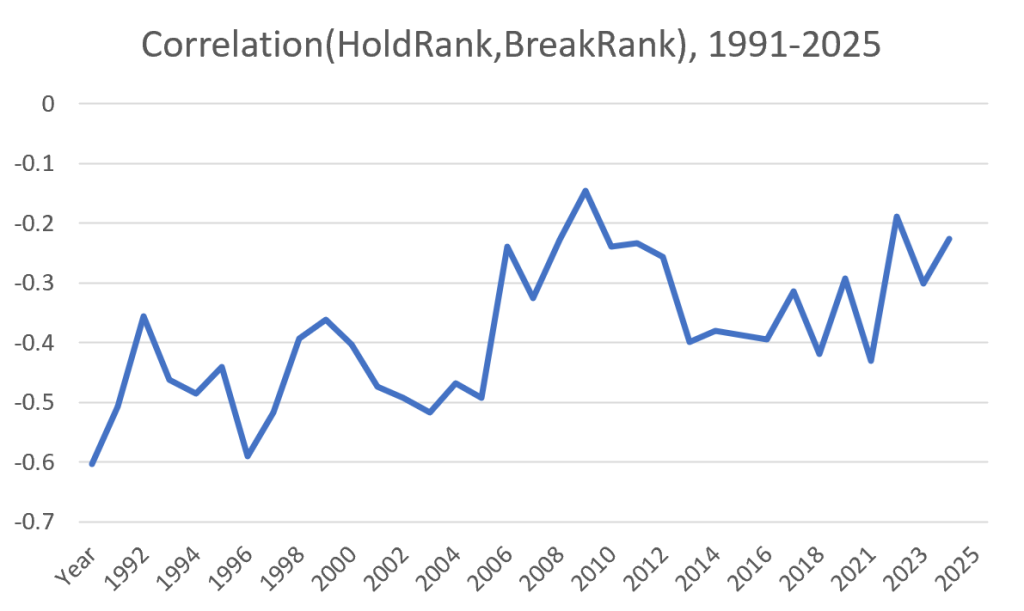

Let me show you the graph from my decline-of-specialization piece again. Generally speaking, it shows how much serve skill is related to return skill. Higher numbers (closer to zero) indicate a closer relationship, or in tennis terms: more all-around players.

Someone on Twitter reasonably asked, what’s up with the peak around 2008-2010? It’s a noisy graph, but a plausible interpretation is that it breaks down into two segments. Up to 2005, most of the data points are between -0.4 and -0.5, with a couple on either side. Since then, the line rarely dips below -0.3. (2013-16 leaves some explaining to do.) Accept this reading, and 2008-10 isn’t a stand-alone peak, it’s the solidification of a new era.

What else was going on in 2008-10? Novak Djokovic won his first slam, and Rafael Nadal established himself as an all-court force. In short, this is when people really started talking about surface speed convergence. Probably not a coincidence.

But why then? Well, in the spring of 1997, the tennis world figured out that polyester strings weren’t just the misguided side-hustle of a bra-strap company. Players with an eye on the future started to switch.

When Guga lifted his trophy, Nadal was 11 years old. Djokovic was 10.

The learning curve

Professional tennis is tough. Players like their gear. They’re used to their gear. It took years for Federer to give up his 90-square-inch frame. Sampras never did abandon his 85-square-incher. When a pro finally does switch, the benefits are hardly instantaneous. It might even mean a temporary step back.

The ultimate advantages go to the tech-natives. For all of Kuerten’s success with Luxilon, he was never going to wring the full benefit of the new technology and the tactics that it implied. If a certain racket/string setup is optimal, the players who do the most with it will be those who built their entire games around it. I don’t know whether the critical age is 8, 11, or 14 (maybe it helped Federer that he was a bit of a late bloomer), but it definitely isn’t 20 or 25.

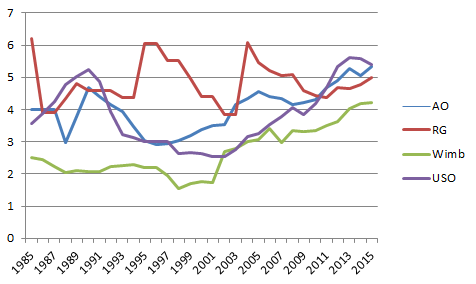

Check out the rally-length graph (based on slam finals) from my 2016 piece:

Wimbledon went from a low in 1998-2001 to a completely different level by 2006-08. Not a coincidence. The slam-finals graph tells the story of a select few guys, but by the late 2000’s, a whole generation of polyester natives–Djokovic, Nadal, Murray, Nalbandian, Berdych, Ferrer, Monfils–had taken over.

None of this requires the surfaces to change one iota. Maybe fans or tournament directors wanted longer rallies, maybe they didn’t. They were going to get baseline tennis no matter what.

Playing styles converged because topspin-powered strategy works across surfaces in a way that no previous style did. Rallies got longer because the players who tried to shorten them were stranded in the forecourt. They fumbled half-volleys into the net or watched passing shots as they whizzed by. Surfaces ended up as the scapegoat for a new era, but they didn’t cause it.