After sustaining a frostbite injury last winter, Hailey Moore started to lean into indoor cycling with Zwift. Follow along for her story of recovery, navigating the stigma around indoor cycling, and why she doesn’t hate riding Zwift…

Every time I ride Zwift, I feel like I have to justify it with an excuse—”I don’t have much time,” “It’s dark outside,” “The weather is bad,” etc, etc. I see my friends do this too, usually followed by the seemingly requisite “I hate riding the trainer” caveat. Of course we’d all rather be riding outdoors, but it seems like the trainer still gets an especially bad rap. After spending some forced time riding indoors last winter—and then continuing to voluntarily ride Zwift intermittently since—I’ve come to a conclusion. I too don’t love riding the trainer—but I also don’t hate it. Here’s why.

Last February, I was invited to a media event hosted by Zwift after which I was gifted one of the brand’s trainers, the Zwift Ride with KICKR CORE 2, to take home and keep (perks!). I’d never owned (or really ridden) an indoor trainer before, and the fortuitous free Zwift couldn’t have come at a better time. Just two weeks before I’d sustained frostbite to both of my pinky toes, though not while riding.

While I consider myself and my toes lucky on the scale of possible frostbite outcomes (read: I still have all ten), the injury put a hard pause on all my outdoor activity for about a month, with return to full recovery being more drawn out.

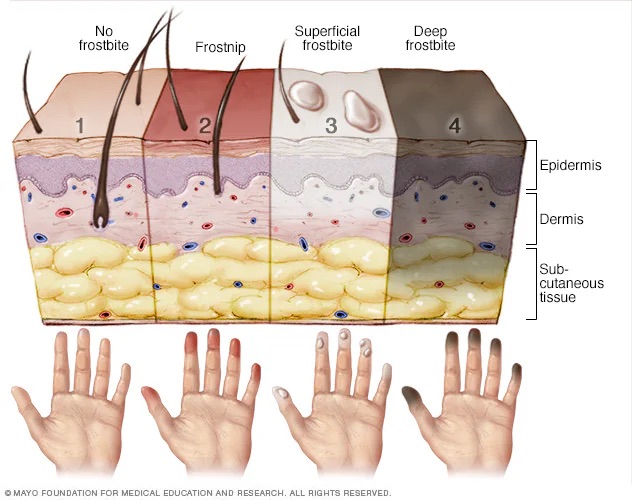

Frostbite severity is graded on a 1 to 4 scale, and my case was a 3. At this level, the body responds to the tissue damage in the same way it would to a burn. At first, the areas became covered in giant blisters—my frost-affected toes looked like they had each grown a new toe. The blisters eventually deflated (I was warned by my doctor not to drain them), and several layers of dead skin sloughed off, leaving the area that had been beneath the blisters raw and incredibly sensitive. Putting on bike shoes was out of the question. My daily drivers during this period of time were an old pair of New Balance road running shoes (with a really stretchy knit upper that I cut holes in to alleviate any pressure on my pinky toes), slip-ons, or my Bedrock sandals with Injinji socks.

It took about a month before I could subject my feet to the confines of bike shoes, and even then I took care, turning to the wide last of a beater pair of Specialized Recons. Still, the toes remained perilously sensitive, and it took some time before I was able to return to mixed-surface riding.

Minor impacts that I typically don’t think twice about—like dropping off a curb, hitting some washboard or potholes, and even road seams—made me wince in pain. Being able to ride the fully stationary and completely impact-free Zwift trainer in that interim, with flat pedals and intentionally blown-out running shoes, was a godsend for my sanity.

Even after my feet would tolerate outdoor riding, I maintained caution. Long-term nerve damage and cold sensitivity are the bugaboos of frostbite. I was warned that, basically forever more, my toes would have increased susceptibility to a repeat case of frostbite, and I would be wise to avoid or minimize cold exposure for a full year following my injury.

March and April are typically the snowiest months in Colorado, where I live, which meant that throughout Spring I was extra selective in choosing days to ride outdoors and, on the days I did ride, I carried plastic produce bags as insurance against getting wet (thus cold) feet. In the past, I’ve been a devoted proponent of toughing out rough weather, priding myself even on being a four-season cyclist. My run-in with frostbite put the brakes on my immediate ability to engage with the elements and, in the long term, effectively lowered my risk tolerance. I got lucky; my situation could have been a lot worse. I won’t make the same mistake twice.

No Baggage

At first I couldn’t do much more than easy spinning (because pressure on the pedals), but eventually, as I waited out the slush and slop of shoulder season, I was able to treat the Zwift like a regular trainer. Most of the complaints I’ve heard about riding a trainer have come from serious cyclists—either former pros, or aspiring ones who live and die by their power numbers and, as a result, have experienced burn-out in training, whether indoors or outside. Before riding Zwift, I’d never ridden with a power meter on any of my bikes (but then again, I’m not a pro and my ability on a bike reflects this).

Still, without the baggage of FTP numbers and power goals, I have been able to approach the performance metrics inherent in the Zwift platform with an outlook of curiosity rather than preconception. True to the virtual form, by limiting the time I ride with a power meter to the trainer, I’m able to fully gamify the Zwift experience. And, because I lack a foundation of formal cycling training, it’s been interesting to have access to Zwift’s extensive workout library. Sometimes I just spin easy and watch Netflix or YouTube, but more often I plug in a workout to pass the time. Regardless, my documented watt output will, at least for the foreseeable future, continue to live in the eponymous abstract world of Watopia and riding outside will continue to be a treat rather than a chore.

Taking the “Fun” Out of Function (i.e. Convenience)

As much as I loathe the word “optimize” and the culture around it—this omnipresent pressure that if you’re not responding to emails while you’re in the checkout line at the grocery store or getting locked in on the daily with a heavy dose of adaptogens and ketones, then you’re somehow not squeezing all of your potential out of life—I can understand the core problem that optimization culture is trying to solve. It’s called being busy. I am also busy. My to-do list is never done and sometimes I read emails in the checkout line. But I don’t like doing this. And I’m trying harder to not feel like I have to be doing multiple things simultaneously as I find far more satisfaction and achieve better emotional wellbeing when I am able to focus solely on the task at hand. And yet…

There are occasional days when it feels too irresponsible to ditch some of my to-do list in favor of getting out for a spin. There are times when the artless efficiency of Zwift actually makes life easier—I can ride for an hour while talking to my mom on the phone, or while keeping a distant eye on a lasagna in the oven, or (yes) even tapping out some emails. I’m ok with this compromise as long as it remains the rare exception to how I exercise (I’ll stop short of calling Zwift “recreating”) and not the norm.

All Gas, No Brakes

On the topic of efficiency, I feel compelled to add that if you are pressed for time, Zwift is a highly effective use of it. You basically don’t have to think about what to wear, or how to layer, when riding it—minimal attire, a hand towel to use as a sweat mop, and several fans are my recommended setup. There is no trying to fit in a quick ride only to find that your tires are flat and need fresh sealant, or that you’ve left your repair kit on a different bike, or that your derailleur needs adjusting, or that your brake pads are shot, or that your lights are dead, etc., etc..

Additionally, once you’ve swung a leg over the trainer, it’s all gas and no brakes—you get every second out of an hour’s ride. No stoplights or crosswalks, or even slowing down to make a turn. The terrain simulation in the Zwift platform, of course, does include descents, but the gearing on the trainer is such that you basically can’t spin out, so there’s no coasting either. I didn’t realize how much stoppage time there can be in a typical ride outside until I started riding Zwift. The continuous pedaling hits your legs different.

Means to an End

The rumors are true: riding the trainer will make you a better rider. Or at least it has made me a better—meaning stronger—rider. I chalk this up to the aforementioned efficiency argument—all that consistent, uninterrupted pedaling adds up. In my case, I also think taking a more intentional approach to riding Zwift and using it for workouts—while letting my mood on the day dictate my effort on the bike outside—has paid dividends. In addition to feeling like my legs are stronger as a result of some semi-consistent Zwifting, I’ve noticed a more subtle benefit.

Most Zwift workouts incorporate a cadence component—measured in RPMs, or the rotations per minute your legs make while pedaling—which is a facility I had never deliberately trained outdoors. Years of loaded riding while touring have made me disproportionately strong at pushing harder gears at a lower cadence, but while riding Zwift I noticed that I have a harder time spinning at a higher cadence with less resistance. By doing very minimal higher-cadence work, I’ve noticed an improvement in my riding outdoors where this skill is relevant—from seated riding on a moderate sustained climb, to quickly pedaling through features on my local mountain bike trails.

Purity Mindset

The last point I’ll make about riding Zwift is the most subjective (this is a Dust-Up after all). Prior to sustaining frostbite, I viewed riding a trainer as lame, or at best as a necessary evil to get through the worst weather. A choice you have to justify with any of the aforementioned excuses I laid out in the intro. The numbers aren’t what motivate me to ride, but by stripping away everything but the data—watts, speed, distance, elevation gain, time, heart rate—I viewed riding a trainer as a kind of inert, soulless facsimile of a more sensory rich experience. The fact that you can’t feel the breeze (unless it’s from a fan) is a metaphorical as well as literal description of riding a trainer. And, like counting carbs per hour, riding Zwift, in some circles, felt coded for caring too much about performance.

But life happens—whether that’s having a kid, getting frostbite, being somewhere in the world with a seasonal shortage of daylight, or simply deprioritizing riding while spending more of your energy on something else—and I don’t think it’s helpful to carry the burden of a purity mindset while trying to balance life’s already difficult and time-demanding challenges. And the truth is, even though I may only line up for a couple races a year, I do care about performance, my own performance, even if that’s only quantified by how I feel on my favorite local climbs. I think personal, off-podium goals are the least-told, but most important narratives in sports marketing. Maybe it’s because the quiet, intrinsic gratification that comes from achieving a personal best doesn’t easily translate to a mass audience—inherently, the relevance and importance of the narrative is individual.

Here’s a thought experiment: Would you rather ride Zwift for two hours every night after your kid goes to sleep and then successfully finish the Tour Divide, or arrive at the Grand Depart undertrained because you couldn’t ride outdoors through winter, then DNF because your knee blows up? This is a hypothetical comparison and, importantly, there is no right answer. But my point is that you get to decide where on the spectrum of short versus long-term gratification you find the most meaning. And the fortunate thing is, that point doesn’t have to be fixed in place forever.

That doesn’t mean that I see the box-checked satisfaction that I get from a dutiful hour spent on Zwift as equal to the more holistic enrichment that riding outside brings me. It’s like ordering and ingesting Sweet Greens versus having the time to shop for and prepare an intentional meal. Rather, I view Zwift as a tool that is unglamorous and obligatory in the short-term but that serves as a powerful means to an end to achieve my broader goals on the bike. It is a compromise that I am consciously making with myself.

I’m lucky to have a space where my trainer can sit in front of a double sliding glass door. The door faces west and on these short, near-winter days I can ride while watching the sun slide behind the peaks of the Boulder skyline, leaving a pastel trail that turns to violet ash in its wake. In between intervals, I look up to give my eyes a break from staring at a screen—through the glass, the horizon is always there, a hopeful reminder of all the better rides out there.