The title here is not misleading. But it is concerned narrowly with the amount of fast bowling Australia play in a Test match. This has consequences for how much fast bowling the visiting batters have to face, how tired the fast bowlers they face are, and so on.

While watching the first day of the fourth Ashes Test at the MCG today, it struck me just how many fast bowlers were bowling today. England had four – Brydon Carse, Gus Atkinson, Josh Tongue and Ben Stokes. Australia fielded five – Michael Neser, Scott Boland, Jhye Richardson, Mitchell Starc and Cameron Green. All nine bowlers on show could bowl (at least) at speeds in the early to mid-eighties.

Since twenty wickets fell on the first day for 266 runs, there was plenty of nostalgia about how batters back in the day had better concentration (its always something mental isn’t it – something nobody can ever test, and can consequently be said with impunity) than players today. It is evidently a view shared by ex-players too, highly regarded coaches among them (though, to be fair, Jason Gillespie’s overall view of things is probably far more considered than that tweet suggests).

The wicket at the MCG had a lot of grass. The Australian captain described the pitch as “quite furry, quite green”, and promptly selected a five man pace attack. When it was announced after Australia’s win at Adelaide that Pat Cummins would be unavailable, I felt that Australia would provide a green top at the MCG. There are 12 WTC points at stake. Australia went one better and ignored the spinner altogether on the predictably green pitch.

While watching the innings today, I kept waiting for the relief against the change bowler for the batting side at 40/4. It never came. Even the West Indies in the days of Clive Lloyd and Viv Richards would bowl Richards or Roger Harper or Larry Gomes or Carl Hooper (later in the 90s) or Jimmy Adams from time to time, even if it was for just three or four overs to give the fast men a breather. In the 20th century, Ben Stokes and Harry Brook, could expect to play an over or two of spin at some point. In todays Test match, they had no such prospect. They knew that it was going to be one fast bowler after another hitting a length and getting unpredictable seam movement. Playing as Brook did (or as Rishabh Pant did in similar conditions in Sydney in early 2025) was not as high risk a play as it must appear to eyes schooled in the staider world of 20th century Australian Test cricket.

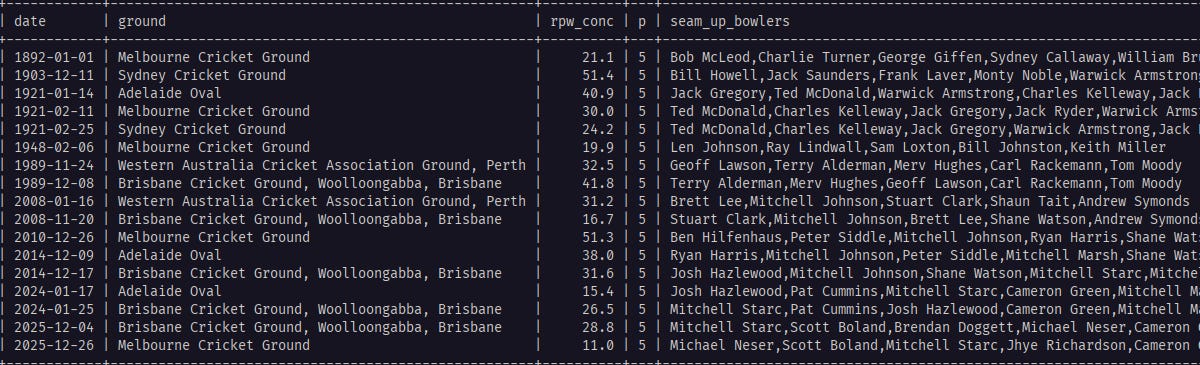

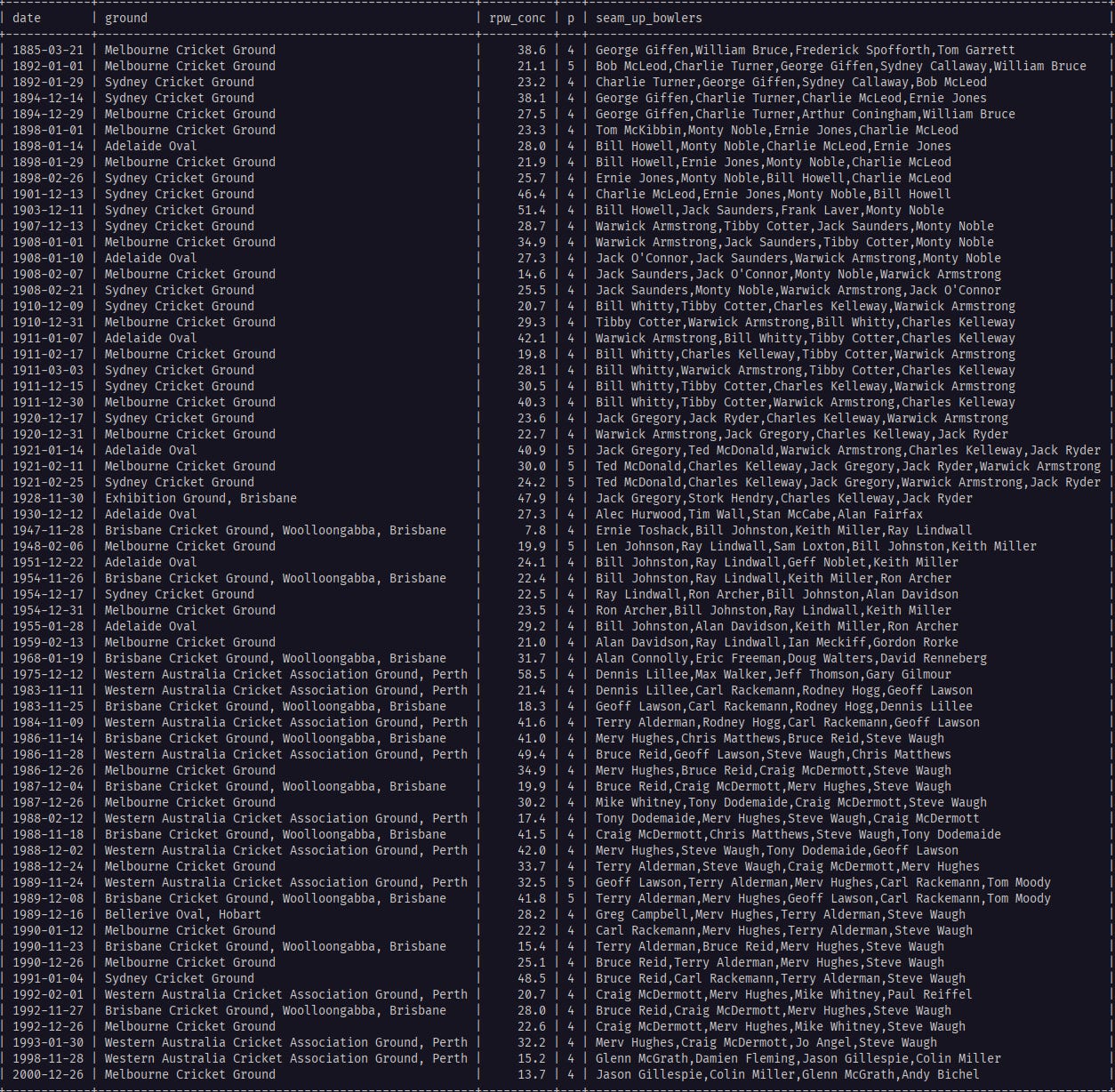

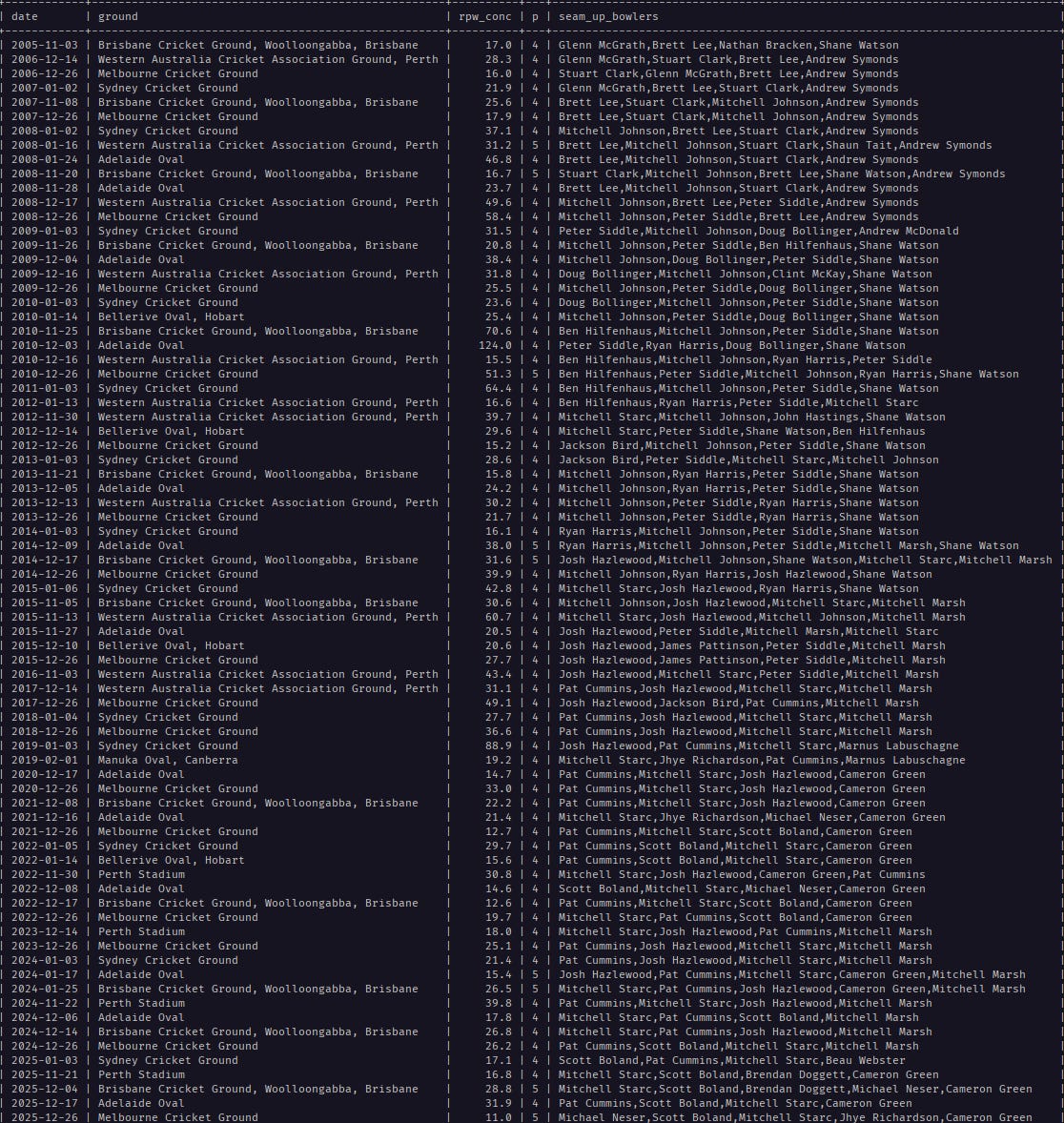

I looked up the amount of fast bowling Australia fielded in Tests in the 20th century. As a standard, I define a fast bowler as a bowler who (a) is classed as medium-fast, fast-medium, fast or medium by ESPNCricinfo, and (b) bowls at least 7% of Australia’s overs in Test cricket). The table below lists all Australian home Tests in which at least four players who satisfied these two conditions bowled for the home team.

Readers will notice that this threshold includes decided part-timers like Steve Waugh (249 wickets in 356 FC matches) and Tom Moody (361 wickets in 300 FC matches). But even so, there is one Test match between 1968 and 1983 when Australia fielded four or five fast bowlers in Test. As as aside, this is perhaps why Dennis Lillee took so many wickets, bowled so many overs, and missed so many Tests for Australia due to injuries. Lillee missed 47 of the 117 Tests Australia played between his debut and his last Test. For much of the 1970s, they used Greg Chappell (291 wickets in 321 FC matches) as their change bowler.

In the 2000s, Australia used Andrew Symonds and Colin Miller (Greg Blewett averaged only 31 balls per Test in his 46 Tests), until Shane Watson, Mitchell Marsh and then Cameron Green and Beau Webster have come along. The bowler who would merely put the ball on a length has gone from Australian fast bowling. They’re prepared to use Travis Head (or Michael Clarke before him) on the finger spin side. But Marnus Labuschagne (91 FC wickets in 173 FC matches) is only used mostly when things are desperate or hopeless.

England played four fast bowlers in this Test match, and they look a bowler light compared to Australia. This is mostly because of the potential effect of Will Jacks bowling five overs for thirty at some point tomorrow in this low scoring match.

For the most part this extra efficiency in modern Test teams is because of the increased run expectation from wicket keepers. Rodney Marsh, with his 26.5 Test average would probably not be considered for the Australian or English Test team of the twenty first century. Nor would Jack Russell or Bruce French or Ian Healy or Bob Taylor or Wally Grout. More runs from the keeper, means room for one more bowler. More bowling depth means less respite for the opposition batters.

On this MCG pitch thirty or forty years ago, the second change bowler would probably be Steve Waugh or a spinner. Ben Stokes and Harry Brook could afford to wait for that. Against today’s Australia, they can’t.

Then there’s the matter of the wobble seam, and the fact, as Steve Smith observed last year “Since 2021 when they changed the Kookaburra ball, batting has definitely got more difficult, particularly at the same time wickets got greener as well.”

There’s little evidence to suggest that today’s players can’t concentrate for long periods of time or that they’re technically weaker than their predecessors from a generation or two ago. But nostalgia is self-fulfilling. It does not concern itself with little things like demonstrable evidence or scrutiny of any record.

Cricket develops in interesting ways. If only we’re prepared to look…

-

Instances of Australia playing five fast bowlers in a Test in Australia – there are two such Tests from 1948 to 2000.

-

Fast bowlers playing for Australia in Tests in Australia in the 19th and 20th centuries.

-

Since 2001: