DiRT Rally was a refreshing surprise upon its Steam Early Access exit a decade ago.

Developed by a skunkworks operation within Codemasters, it moved away from the arcadey, over-the-top ‘dudebro’ shenanigans of the DIRT franchise toward a more realistic take on the rally genre.

And boy, did it deliver.

The game reached version 1.0 on 7th December, 2015, releasing with over 40 cars and 36 stages based in six real-world environments, including officially licensed World Rallycross content and the Pikes Peak Hillclimb course.

Ten years on, as Codemasters bows out of rally game development and Assetto Corsa Rally begins its Early Access journey, it’s time to reflect on why DR was such a huge success, with first-hand insights from Game Director Paul Coleman.

DiRT Rally: origins

My first experience of DiRT Rally was a literal eye-opener. Piloting a Lancia Stratos down a narrow Welsh forest road at night, with a sonorous Ferrari V6 barking behind me, was simply magical, as the beaming light pods punctured the darkness ahead.

The game looked incredible, far superior to direct rivals Sébastien Loeb Rally Evo (which released in January 2016) and WRC 5, but it also had genre-leading audio, with exhaust notes and ambient effects captured in exacting detail.

This is remarkable, given how small the development team was, consisting mostly of 10-15 passionate rally fans. It came at a crucial point for Codemasters, too.

“It was a difficult time for Codemasters; money was tight,” stated Coleman to Traxion.

“It got to the point where there was no money for the service teams to order in more toilet roll because the bills hadn’t been paid,” he explains, underlining the company’s financial (and toiletry) struggles.

“From a business perspective, they [Codemasters] had just made GRID 2, it hadn’t been as successful as they wanted it to be… Our pay slips had been pushed further and further back into the month until they couldn’t get any later,” continued Coleman.

The need for a new money-spinning title was greater than ever, then, but the studio first had to work out a conundrum.

“With DIRT 3, we were kind of walking around telling people: ‘Hey, you’ve got all of this cool rally content, but then also you get to do all of this awesome Ken Block stuff,’ so it felt like we were trying to sell two different games in one package.

“It was right after a large number of the studio splintered off to make Playground Games, which obviously went on to make Forza Horizon and were very successful there, but we were essentially just trying to gather the team around a new product and build something that continued to make the DIRT franchise successful.

“So DIRT 3 had that, but also this kind of split persona.”

Split personality

Being a relatively small studio, personnel had been working on GRID 2 and DiRT 3 simultaneously, holding up development of the former. This gave the management team at Codemasters a financial headache. However, it soon leaned into the idea of this ‘split persona’ for DIRT.

“The only corporate, quick and sensible solution was to take [DIRT] 3 and choose whether to do a more rally-focused game or a more kind of fun party mode-based experience,” said Coleman.

“And in the time frame that we had, and with the trajectory that Ken Block was heading on in terms of his popularity and success, and the fact that we wanted to reach out to a more casual audience than we’ve been able to hit with DIRT 3, [DIRT] Showdown was born.

“And I think that gave us the permission we needed to start working on a more focused rally title internally. There would be the Showdown games where, you know, fun party stuff would happen, and then we would do something more serious, more motorsport-oriented, still within the off-road space,” he concluded, explaining the game’s genesis.

Maximum attack

With the Rally spin-off officially greenlit, Coleman’s tiny team set to work on creating an approachable but authentic rally title, with Steam’s Early Access program giving the studio leeway to work through player feedback and drip-feed more content.

Coleman attributes much of the success of the game around this period to Community Manager Lee Williams, who was instrumental in keeping fans engaged, even when visible progress had stalled.

Although it wasn’t designed to be a full-on simulation, DR offered enough nuance to win over hardcore sim fans, as cambers convincingly hooked your car through corners, with stones pebbledashing the chassis, punctuated by pacenotes from your co-driver (voiced by Coleman himself)

The calls were recorded live, using the same intercom system he used while co-driving for real in his spare time. And just to up the realism further, he was also strapped into a motion rig.

“We would crank the D-BOX up to its absolute maximum settings, so it was literally jumping off the floor,” reminisces Coleman with a smile.

“And then one of the level designers would drive the stage and I would co-drive to them, driving the stage… that sort of hit that you get through the landings, we wanted to try and capture that in the sound.”

Dear God

That visceral experience extended to vehicle engine and exhaust sounds, with owners of rare rally exotica persuaded to allow their cars to be recorded.

“They [DR’s audio team] were almost like salespeople… because they were cold-calling these guys with these quite rare rally cars and begging them to put them out onto the track so we could record them.

“They would essentially try and keep the cost right down. Oftentimes, we would literally just be paying for the race fuel… We would jump on a test session that they were already doing, mic a car up and essentially record it while it was being tested for an event,” stated Coleman, citing the game’s audio team’s ‘miracle’ work in obtaining high-quality sounds for a pittance.

“I think getting the right audio soundtrack into an experience can make the difference between a game feeling good and a game feeling awesome,” he added.

There were cars from all eras of rallying in the game, with the Group A Subaru Impreza’s distinctive bark gloriously replicated. So too were the intake howls, supercharged hisses and turbo whirrs of the Group B-era cars, five of which made it into the final game.

Modern WRC cars like the Hyundai i20 emitted aggressive and purposeful notes, while Formula 2 kit cars seemingly revved to infinity. But let’s circle back to my earlier experience in the forests of Wales.

Spot on

“The Stratos is a really good example of a car that was recorded properly,” Coleman recalls.

“I think it was, it was Steve Perez’s car … I believe it was either his driveway or it was where the workshop where the car was kept, they had like a lane that it could be driven down.

“Our audio team were very, very particular about not putting a car on a rolling road and actually putting the car on either an airfield or a track where the car can go through its gears, and the load is recorded.

“So, as the car kind of changes up through the gears, you hear the transmission and the engine and the exhaust all have their various wobbles and flutters,” he explains, once again emphasising the level of detail the development team strived for.

The game’s graphics were a triumph, even working well on VR headsets to provide an extra layer of immersion. The team was familiar with Codemasters’ Ego Engine, a graphics system that had been employed in some form or another since 2008, so recreating the game’s environments in a satisfactory way wasn’t a concern for Coleman:

“Everything was very handcrafted and built in the old way, but because it was the old way, we knew it was robust, and we could make it work. So it was just a case of making sure that we didn’t have too many trees to make the frame rate die,” he commented.

“I have seen some comments since the switch to Unreal [Codemasters switched to Unreal Engine for EA SPORTS WRC, DiRT Rally 2.0’s successor] that happened with WRC about how DiRT Rally still looked better,” he began, alluding to one of the more controversial aspects of Codemasters’ recent history.

“And the weirdest thing is that DiRT Rally in prototype form looked even better than what we released,” he revealed.

“But the loss of the Art Director [Harvey Parker]… that prototype kind of got lost with him, and we never were able to sort of recapture that.”

Licence to thrill

Inevitably, with rallying having such a rich history and fans who demand realism in their racing titles, DiRT Rally needed to license many actual rally cars, which wasn’t the easiest of tasks given Codemasters’ financial difficulties.

Some models did require an up-front licencing fee, but other agreements were negotiated based on a royalty payment post launch and up to a certain threshold, thus cutting down on in-development investment.

The game also featured a fully licensed version of the Pikes Peak International Hill Climb. This added both asphalt, gravel and mixed surface versions of the famous Colorado point-to-point, allowing players to replicate the iconic Climb Dance movie, starring Ari Vatanen and his Peugeot 405 T16.

For rally aficionados, it was also possible to drive Sébastien Loeb’s bonkers Peugeot 208 T16 on the asphalt version of the route.

“When it came to Pikes Peak, that agreement was done before Gran Turismo signed an exclusivity deal. I’m sure some money changed hands for Pikes, but I don’t think it was a huge amount,” said Coleman, outlining why the fan favourite rally stage hasn’t appeared in any other video game since.

The game also captured the essence of famous rally stages, including Col de Turini, Sweet Lamb, and those found in Sweden’s Värmland province and Germany’s Baumholder military base.

Uniquely, DR contained official FIA World Rallycross content. This came at a crucial time for WorldRX promoter IMG, which had just transitioned the European Rallycross championship into a global series.

Rallycross is box office entertainment: short races, 600 bhp cars and enough sideways action to make Travis Pastrana say ‘steady on, that’s a bit much.’ Also, thanks to the addition of former World Rally Champion Petter Solberg, the sport’s popularity had exploded. It was therefore a natural fit for video games, and DR’s punchy handling model was ideally suited.

“World Rallycross was really interesting… We explained to them how much we were investing in, obviously, making the tracks, building the cars [and] we showed them the road map of the tracks that we wanted to add.

“And so they agreed to do a deal where essentially, we would represent the sport in the best way we possibly could… but there wouldn’t be any payment until further down the line,” stated Coleman, explaining how IMG and Codemasters invested in each other’s potential to build a partnership.

Fortunately, the ‘gamble’ worked out well for both parties, with 2019’s DiRT Rally 2.0 going on to feature a more fleshed-out WorldRX mode, which included seven cars and 13 official tracks, including old and new venues like Lohéac and the Yas Marina Circuit.

Sadly, there was no Hoonigan Racing Division Ford Focus RS, many people’s favourite from that era. As Mr Block’s allegiance had switched to Microsoft, it was busy being the face of Forza Horizon 3’s Blizzard Mountain DLC. That pesky Codemasters – Playground Games split rearing its head again…

The appearance of official motorsport licenses legitimised the first instalment in many motorsport fans ’ eyes, making it an easy purchase for certain subsets of motorsport fandom. WorldRX commentator Andrew Coley even became the voice of the game’s tutorials section, where a broad range of rally-based topics were covered in detail.

Light features

Although the game had solid content, its comparatively low budget and tight turnaround were perhaps visible in its main menu and career mode designs.

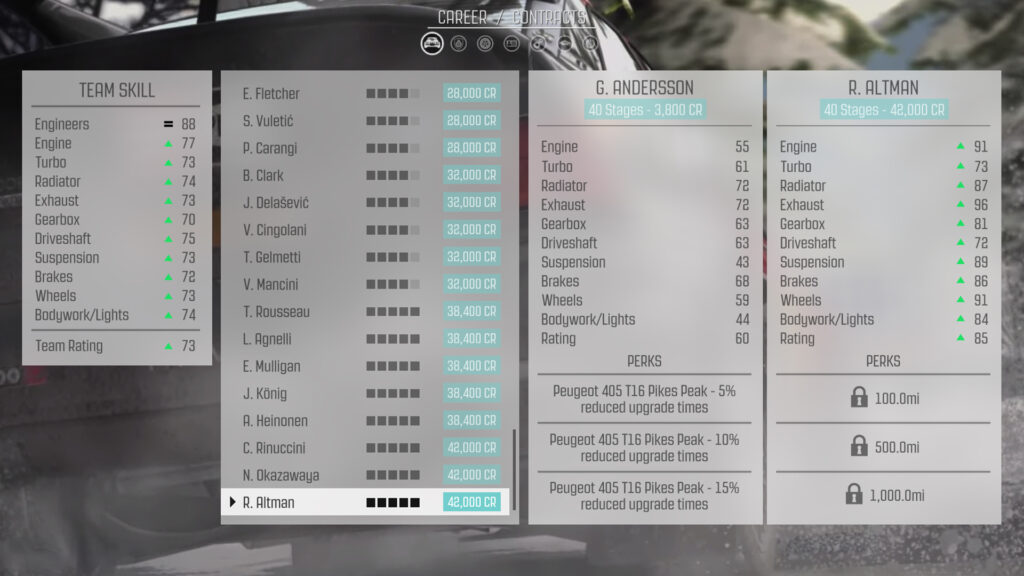

A fairly spartan user interface was backed up by a solid, if unspectacular, career mode, which revolved around completing rallies and purchasing cars, all the while building up your team of engineers. Raising their stats allowed your car to be fixed more quickly, with specific perks unlocked for each individual.

Hiring more skilled engineers was more expensive, but a lower-rated staff member may have better perks to exploit: for example, ‘G. Andersson’ had average stats but had perks which reduced the time it took to upgrade the Peugeot 405 T16 Pikes Peak car, which came in handy.

Career mode cycled through the game’s six rally environments, with difficulty increasing as you progressed.

It’s a similar deal with rallycross, with just three circuits (Lydden, Höljes and Hell), so it gets quite samey after a while, with various versions of Pikes Peak arguably also failing to hold long-term interest. Buying every car and levelling up your engineers to maximum levels was a bit of a grind; something DR 2.0 addressed by adding more content.

There was a multiplayer ‘Leagues’ mode, however, which allowed players to create online rallies, and this was a certified hit with fans, being expanded into ‘Clubs’ for the sequel. Sadly, however, the servers were only recently shut down, denying players the ability to play online.

Console conversions were also massively successful thanks to near-perfect ports, which shouldn’t have been a surprise given Ego’s suitability for the task. Official sales figures are hard to come by, but judging by chart positions and player numbers, over one million copies is a safe estimate.

However, the game’s biggest weak point was how the cars felt to drive on asphalt, with an unnaturally vague sensation at odds with how DR’s vehicles handled gravel. It was manageable once you acclimatised, but there was clear room for improvement.

Regrets

Despite the project’s undoubted success, Coleman regrets that the DiRT Rally franchise hadn’t been condensed into a long-term, live service platform.

“One of the conversations that was happening was what to do after DIRT 4. And the conversations about DIRT 5 quickly changed to ‘let’s make DiRT Rally 2’. And I just wish that we’d not had DIRT 4 in the middle of it. I feel like Dirt Rally, continued into a service, would have been a much stronger offering.

“So I just wish we’d been able to sort of join those two things together into DiRT Rally: the service and maybe that would have still been operating today… Hindsight being a wonderful thing, but the WRC licence could have been included in that and then removed from it without it needing to stop as a product,” he lamented, referencing DR 2.0’s officially licensed successor, EA SPORTS WRC, which arrived after Codemasters was purchased by global publishing giant, Electronic Arts (a deal worth an eye-wateringring $1.2 billion).

Saviour

Although the game had some flaws (being a motorsport photographer, my personal gripe is that there was no photo mode) DiRT Rally was an overwhelming success for Codemasters, garnering critical and public acclaim.

The studio treaded the delicate balancing act between creating an authentic enough experience for motorsport and sim aficionados, while also making it approachable enough for newbies to pick up and play with a controller.

However, for the company, the sales success of its rally offshoot meant much, much more.

“Did DiRT Rally save Codemasters?” reflects Coleman. “I think it saved the day insofar as revenue was coming in every week – Steam is great for that… I think it had a very big part in Codemasters continuing to exist,” he concluded.

It’s bittersweet to extoll the virtues of a game when its developer has been sidelined, perhaps permanently, but much of the DR team has moved on to other studios and projects anyway, with Coleman himself moving to a Creative Director role at iRacing in 2022.

Having played DiRT Rally to refresh my memory, I was surprised at how well it stood up in terms of gameplay, with its graphics looking – dare I say it – fresher than EA SPORTS WRC. It’s a testament to the skill and ambition of Coleman and his team that they could overcome the game’s embryonic struggles to create such a polished product.

So much so that double-quilted toilet roll was back on the studio’s shopping list.