PAK beat USA by 32 runs, in a game that wasn’t as close as the scoreline suggested. It was a blowout, with PAK’s batters all but ending the game in the first innings.

But, what happened beyond the headlines?

-

🏏 PAK’s batters aren’t great, but tonight proved the best way to use them.

-

👟 How one USA pacer withstood the PAK onslaught with slower deliveries.

If you’re reading this online, remember: you can get it via WhatsApp or direct to your email👇!

✍️ Written by Tarutr Malhotra, who runs Best of Cricket.

Since the start of 2024, Pakistan have played 67 completed T20Is. As is to be expected of a team with 4 different coaches during the time, their lineups have been…varied. They have a less than stellar 53.7% win rate, despite playing 17 games against “weaker” opposition (the associate nations, plus Ireland & Zimbabwe).

Without getting into whether those teams are actually “weaker” – PAK have lost just 3 of 17 against them – it’s a fairly abysmal win-loss ratio for the schedule. However, there is one playing XI choice that makes a huge difference.

When Saim Ayub & Sahibzada Farhan take on the new ball, PAK have won 78.57% of their games since 2024. Every other opening pair – including versions with just one of Farhan or Ayub – drops that win rate to 35.9% in the same period.

As we saw today, they can be a fairly devastating combination – if not a long lasting one. Their partnership of 54 (31) gave PAK the foundation to make sure they wouldn’t slip up a second time to USA in a T20 World Cup.

So, what makes them useful at the top? Both players are relatively quick compared to their national team peers. Farhan strikes at 8.1 runs per over & Ayub at 8.3 RPO since 2024, compared to PAK’s overall 7.6 RPO in the powerplay.

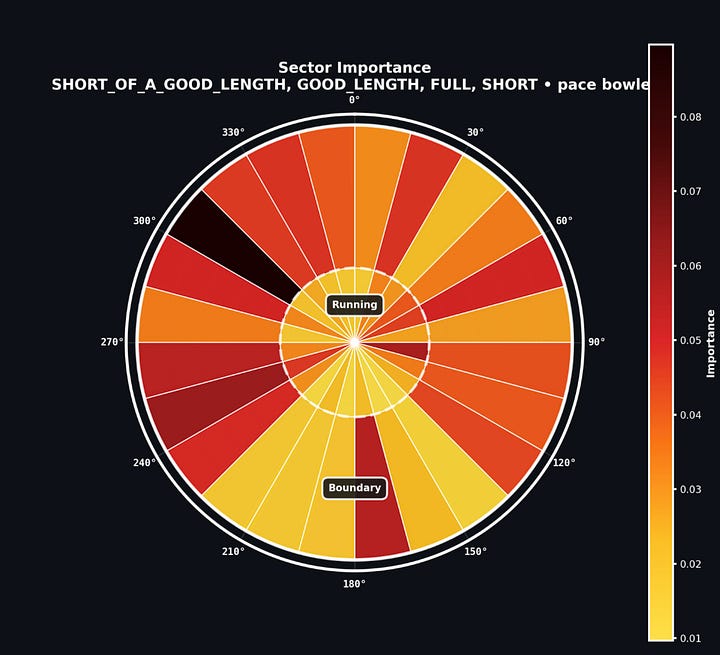

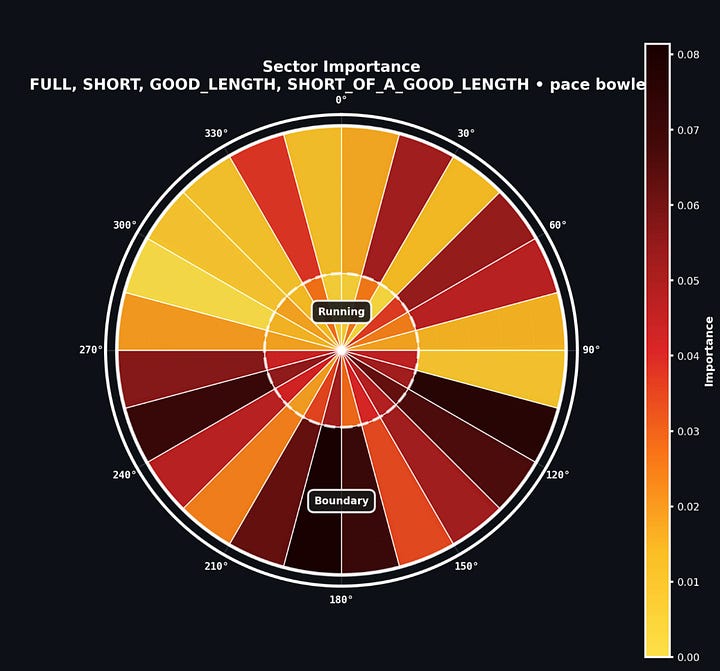

Also, in addition to the natural confusion caused by an LHB-RHB combo, they also have different areas of hitting expertise. As the shot charts against powerplay pace show, Ayub favours legside drives & pulls, while Farhan is better down the ground.

You would assume these minor advantages only count against “weaker” teams, but ironically, the partnership tends to do better against the stronger full member sides. And it’s not a small sample size – they’ve played 8 games against “weaker” teams (associates, plus IRE & ZIM) and 20 games against “peer” teams since the start of 2024.

Versus the “weaker” sides, the Ayub-Farhan partnership lasts 11 balls on average versus 18 balls against “peer” nations. Similarly, PAK’s powerplay scores with Ayub-Farhan opening jump from an average of 36.88 runs (v. “weaker” teams) to 47.64 runs (v. “peer” teams). [I never said PAK’s opening pair were elite – just the best they have!]

Moreover, this pairing sorts out PAK’s middle order. In particular, it knocks Babar Azam down to a role that he is more suited to play. Since the start of 2024, he has opened the batting 10 times and averaged 26.2. Comparatively, in the 26 middle order innings he’s played, he’s averaged 37.2.

It’s not rocket science; Azam can play out T20 spin better than he can pace. He averages just 17.7 v pace since 2024, and 37.2 v spin (with fairly similar strike rates). [The spin and middle over averages being identical is just a funny coincidence.]

Additionally, Azam needs time to settle in, which the requirements of powerplay batting don’t allow. Since 2024, he strikes at just 104 in his first 10 balls – but accelerates to 133 in the 11-20 ball range, and 142 in the 20+ ball range.

That pattern played out again today. Azam scored 7 (10) in his first 10 balls, 16 (10) in the 11-20 ball range, and 23 (12) thereafter. It helped him put together a vital 81 (53) partnership with Farhan that all but ended tonight’s contest in the first innings.

It didn’t hurt that he came out after the powerplay, and PAK were at 56-2. That may not seem the best total against a side like USA, but PAK have only averaged a powerplay score of 35.17 runs v. associate teams since the start of 2024.

PAK’s batting order is not great. There’s no two ways about it. But, Ayub-Farhan at the top & Babar after the fielders go back is their best option at maximising the resources they have. With enough bowling fireworks, it gives The Falcons an outside chance of pulling off those unexpected tournament upsets they’re famous for.

Data from ESPNcricinfo, Cricmetric, the Jio broadcast, & FieldToolKit.

If you’re reading this online, remember: you can get it via WhatsApp or direct to your email👇!

✍️ Written by Raunak Thakur, who runs Dead Pitch’s Society. Follow him on X.

Shadley van Schalkwyk was the clear outlier for USA when almost everything else went wrong. The other five American bowlers conceded 163-3 in their 16 overs at an RPO of 10.2, while van Schalkwyk managed to limit the PAK batters to just 25-4 at 6.25 RPO – identical figures as against India over the weekend.

On a surface offering true bounce and easy carry, the other pacers looked more reactive rather than prepared. Saurabh Netravalkar searched for swing that never appeared, drifting in line and length without reference to his field. Milind Kumar had a confused single over spraying it everywhere, while debutant Ehsan Adil struggled to hit consistent lengths, feeding pace into a surface that rewarded clean striking.

The spinners weren’t much better. Harmeet Singh went short and full with no consistent lengths, while Mohammad Mohsin, despite a respectable economy of 6.75, was easily milked in the middle overs to keep any potential run pressure down after van Schalkwyk picked up two wickets in the last powerplay over.

The South Africa-born pacer worked to a different rhythm. He trusted the pitch, bowled into it, and took pace off with purpose. Cutters and slower balls replaced hit-the-deck pace, and his fields were set for mishits rather than miracles. The same bounce that punished the rest became a separator in his hands. Batters committed early, found the ball arriving later than expected, and paid for it.

Saim Ayub’s dismissal in particular was a great example in how he crafted the wickets over multiple balls rather than hoping for a lucky mishit. The Sinhalese Sports Club in Colombo has offered the most bounce of any venue this World Cup, and van Schalkwyk leaned into what the pitch was giving him.

The pacer was first brought on in the 4th over after USA had already conceded 32-0. Ayub looked in no mood to let van Schalkwyk settle, and charged down the pitch immediately to manufacture room to slog the ball over the cover region. That first full-blooded attempt produced a thick outside edge that ran down to short third man for 4. The boundary eased the pressure, but the warning stayed. The bat was already moving ahead of the ball.

Then came a reminder of why the PAK batter had to attack van Schalkwyk. A 130 kph delivery was forced into the off side, unable to beat point. When pace was on, Ayub could not create angles. Therefore, when the pace was off, he had to manufacture them.

van Schalkwyk kept pressing the same buttons. A short ball followed, not aimed at dismissal but at testing the bounce. Ayub swayed inside the line, confirming that the surface stayed true even when pushed back. An off cutter was bowled hard into the pitch and dragged towards extra cover.

The pacer then sent down the expected slower ball. An off cutter rolled into the pitch at just over 111 kph, climbing off the surface. Ayub went after it again, throwing his hands through the line, producing another miscue that skewed towards cover and fell just short of the fielder.

Two false shots induced in a single over, both surviving more on fortune than control.

At the start of the sixth over, the battle resumed. The pattern was clear. Ayub shuffled wider across his stumps, briefly exposing his leg stump as he looked to go over the covers. Van Schalkwyk followed him further outside off, choosing a wider cutter and taking even more pace off, this one closer to 107 kph. The slower speed pulled Ayub deeper into the shot.

The bounce held, just evaded the batter’s control, and the edge carried straight to short third man. After the PAK opener had hammered USA with multiple boundaries in the powerplay, van Schalkwyk had the last laugh.

Hard lengths outside off, subtle changes of pace, and trust in the bounce on offer narrowed Ayub’s options. Against a left hander repeatedly targeting the cover region, the bowler did not need swing or extravagant movement. Ayub was ultimately undone by a lack of pace while trying to make space on a ball that never stopped rising.

Similarly, van Schalkwyk picked up the wicket of the PAK captain with more mild variations and sudden slower balls. Salman Ali Agha misread another slower ball, and mistimed his pull to deep fine leg in the same sixth over.

At the death, with PAK forced into acceleration, van Schalkwyk leaned into creating uncertainty.

Shadab Khan’s wicket arrived from repetition. After being struck, he returned to the slower short ball, slightly wider and climbing a fraction more off the surface. The bounce, already a known quantity by then, hurried the stroke while the reduced pace delayed the bat. The pull was shaped early, finished late, and lobbed straight up.

Faheem Ashraf’s dismissal closed the loop. One ball faced, similar width outside off, similar reduction in pace. Ashraf looked to hit on the bounce through the off side and was drawn into the shot too soon, producing the familiar thick edge. Short third man remained in play because the plan demanded it.

Across left handers and right handers, van Schalkwyk relied on the same elements. Cutters into the pitch, subtle changes in pace, and fields aligned with where mistimed contact was most likely to land. The wickets followed from timing being repeatedly compromised on a surface that never stopped offering bounce.

Data from ESPNcricinfo.

If you’re reading this online, remember: you can get it via WhatsApp or direct to your email👇!