Dodgers fans know and love their home in Chavez Ravine, which is among the oldest stadiums in baseball and one of the sport’s “true cathedrals,” but the team’s former home in Brooklyn played an important role in the sport’s history.

The reigning back-to-back World Series champions have played in Dodger Stadium since 1962, but Ebbets Field is still remembered today for the community the team built there and its impact on baseball.

The Boys in Blue in Brooklyn

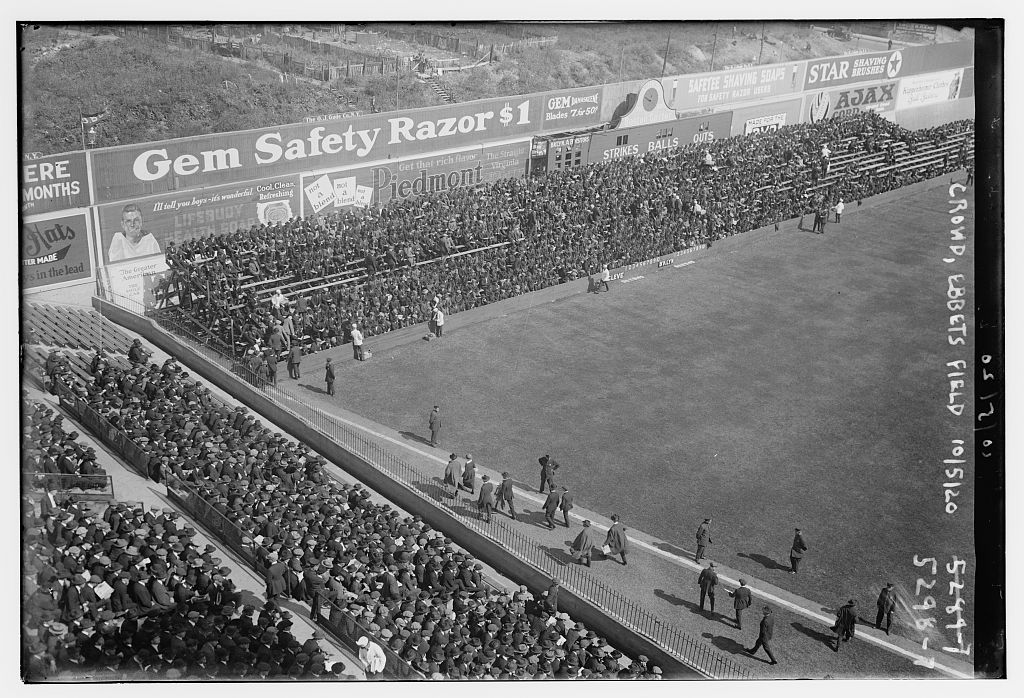

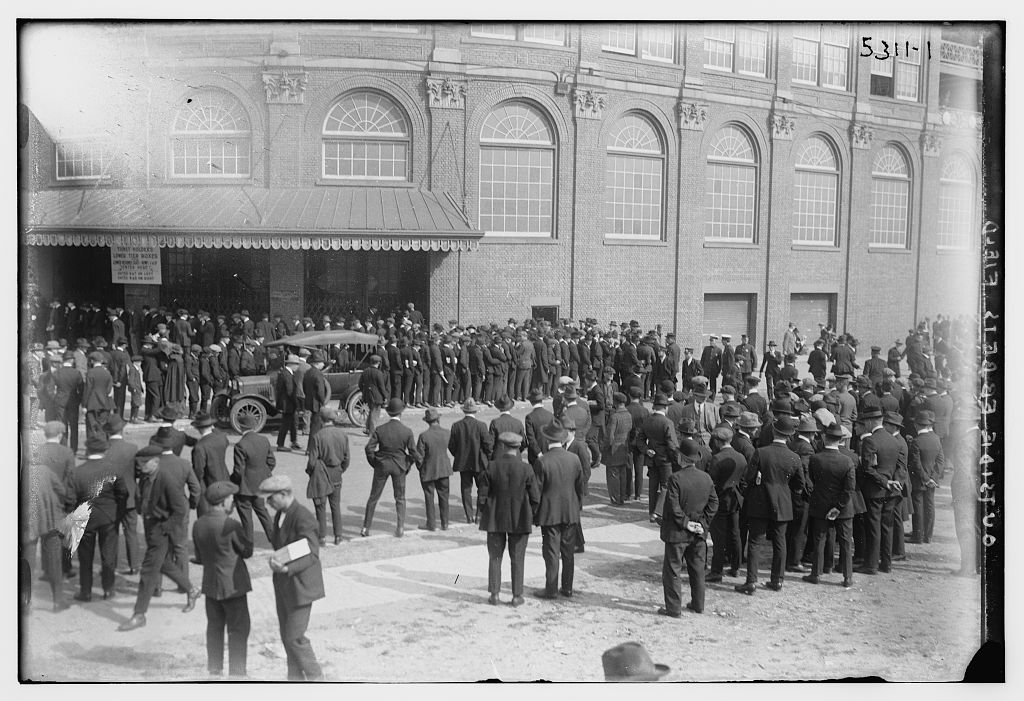

The Brooklyn Dodgers called Ebbets Field home from 1913 to 1956, but the venue was more than just a place for the local team to play baseball, said Bruce Hellerstein, the founder, president and curator of the National Ballpark Museum.

“The operative word is community … I tell people history will never repeat itself. You’ll never see a community like this, and it’s been called the most beloved ballpark and the most beloved team in the history of baseball. I mean, that covers a pretty big ground,” he told Dodgers Nation.

Not only was the Brooklyn neighborhood largely supportive of the Dodgers’ success, but those neighbors sometimes included the players themselves.

“My understanding is a good share of the Dodgers actually lived there, right in Flatbush,” Hellerstein explained. “I mean, hello! Where do you see that happening?”

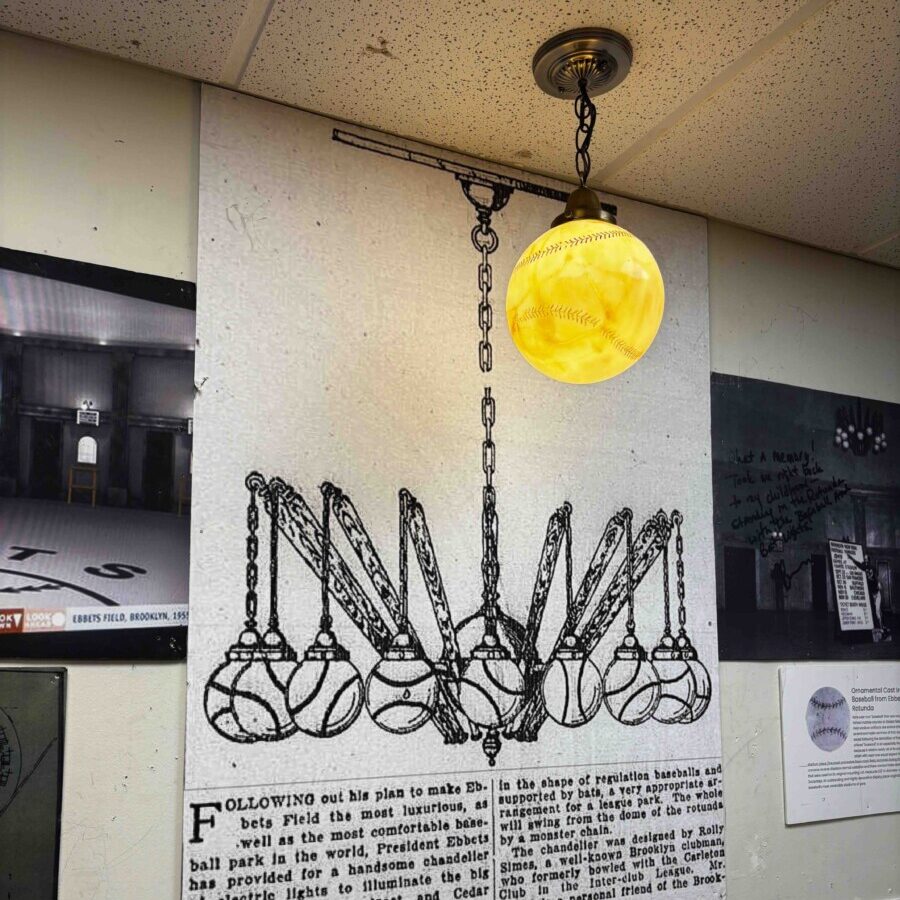

The players also entered through the same rotunda entrance near home plate that the fans used, the exterior of which is reflected in that of the Mets’ home of Citi Field.

In addition, Citi Field features a similar rotunda, this one named for Jackie Robinson, who broke the color barrier in Major League Baseball.

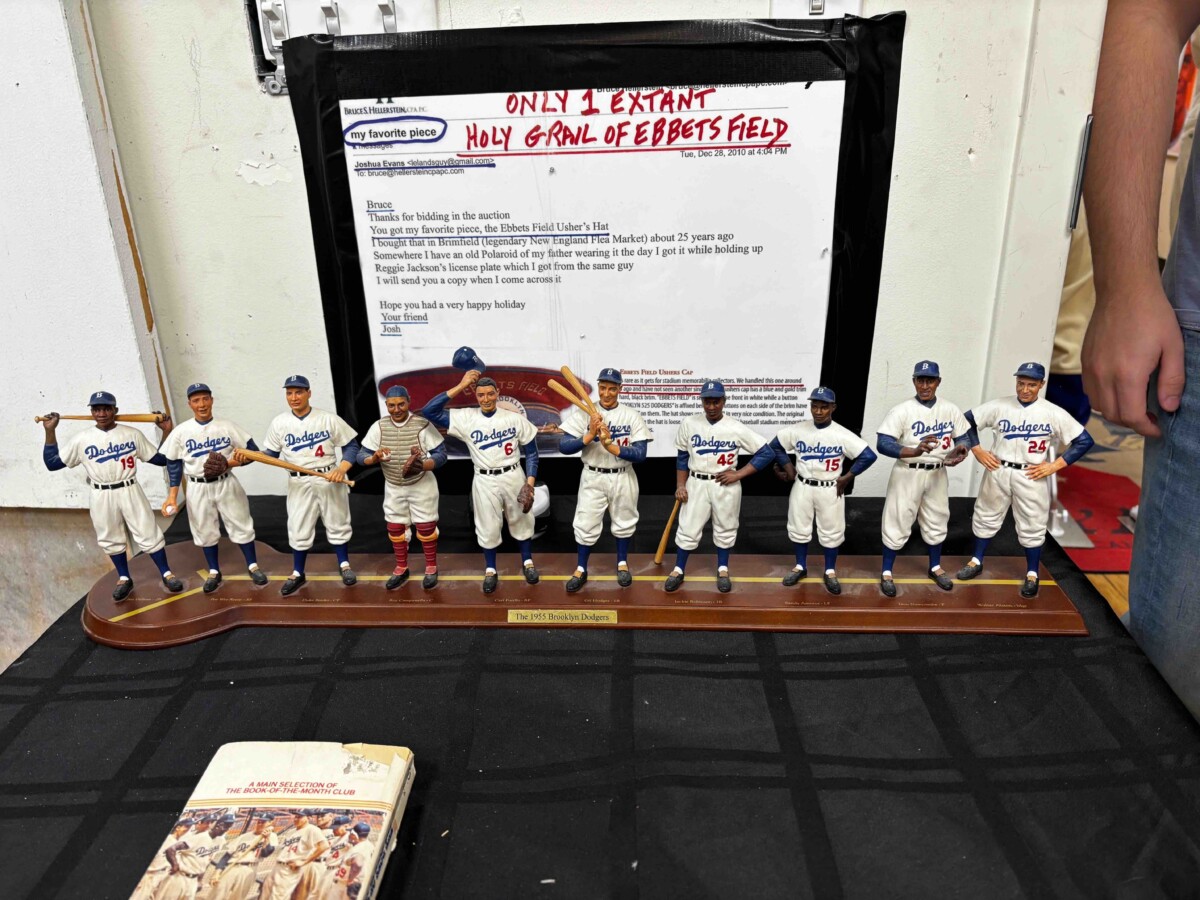

How Ebbets Field Ushered in a New Era of Inclusivity

It was at Ebbets Field that Robinson and three others broke another color barrier, becoming the first Black players to play in the All-Star Game.

Robinson was joined by fellow Dodgers Roy Campanella and Don Newcombe and Larry Doby of the Cleveland Indians, something Hellerstein believes was only possible because the game was played at Ebbets Field.

“It took baseball two years to include Blacks in an All-Star Game,” he said. “And we’ll never know the answer, but if they did not have that at Ebbets Field, I’m not sure how many years it would have taken to include Blacks in an All-Star Game.”

What Would’ve Happened if the Dodgers Never Left Brooklyn?

Hellerstein didn’t mince words when he said what the Dodgers’ departure did to the Brooklyn neighborhood it once called home.

“They took the heart of the neighborhood,” Hellerstein said. “If I came over and ripped all your limbs off, I think it was worse than that.”

He said many Brooklynites swore off baseball altogether after the team packed up and moved west. But he admits that the team would’ve been at risk of folding if a drastic move wasn’t made.

“The neighborhood at Ebbets was getting really bad and their attendance was decreasing … I don’t think it would have lasted,” Hellerstein said. “But there’s other alternatives besides just yanking it 2,000 miles away.”

What is the Lasting Legacy of Ebbets Field?

Today, when fans think of the hyperlocal impact of Dodger Stadium, the Battle of Chavez Ravine and the displacement of Latino families is what springs to mind.

But for Hellerstein, it’s important to remember that the residents of Brooklyn also lost a lynchpin of their community when the Dodgers moved west ahead of the 1958 season.

“I don’t think there’s any question, at least in my mind, this was a community asset that was pulled from the community,” he said.

Today, Hellerstein’s National Ballpark Museum near Coors Field in Denver, which also features an Ebbets-esque rotunda, is host to artifacts from Ebbets and the 13 other classic ballparks. The modest space began as an extension of Hellerstein’s personal collection before transforming into a nonprofit organization.

Hellerstein, 77, is currently mourning the death of his wife, Judy, and hopes to one day dedicate a portion of the museum to her. He says the museum operates at a loss and rent prices have put the space at risk of closing. But his passion and love for the preservation of the sport’s forgotten relics, as well as his desire to honor his wife, keeps him motivated to do whatever it takes to keep the doors open.

Hellerstein says donations are welcome, appreciated and needed to keep the National Ballpark Museum open. To contribute, click here.

Travis Schlepp contributed to this story.