Known for the way it blends classic fabrication techniques with modern finish work, Mosaic Cycles is a titanium maker of custom-order and batch-built bikes in Boulder, Colorado. Hailey Moore pays a Shop Visit to the Mosaic Cycles HQ and sits down for a Q&A with Mosaic’s founder, Aaron Barchek, and head of Marketing & Sales, Mark Currie.

There are two sets of heavily lugged, large tires resting against the building that houses Mosaic Cycles’ fabrication headquarters in Boulder, Colorado. But these tires are—like—giant. They’re the kind whose ability to roll is a bug, not a feature, the ones that you lift and flip over rather than ride, and they belong to the powerlifting gym that sandwiches Mosaic on one side; the warehouse for a local meadery serves as the brand’s neighbor on the other.

Tucked in a low-slung industrial commercial space off of one of Boulder’s central bike-path arteries, it’s an unassuming locale for a brand that has become steadily renowned for its MUSA titanium frames and ornate finishes over the past 15-odd years.

Originally hailing from St. Louis, Aaron Barchek started Mosaic Cycles in 2009. And although he cops to having technically moved to Boulder for college—where plans to pursue engineering quickly shifted to studying integrated physiology—he credits taking a framebuilding course at the United Bicycle Institute in 2002 and, after, working as a welder at Dean Cycles for seven years as the real educational foundation that allowed him to launch Mosaic.

“The way I describe it is, when I started out, I was full-time college, part-time bikes, and by the end it was full-time bikes, part-time college,” Barchek told me while giving me a tour of Mosaic’s space. He went on, “I was lucky to graduate. And at the end of that, it was pretty clear that if I wanted to continue pursuing bikes sustainably, as a career, I’d have to figure that out in a larger scope. And I guess the solution was to start a small business.”

A Fabricator’s Mis En Place

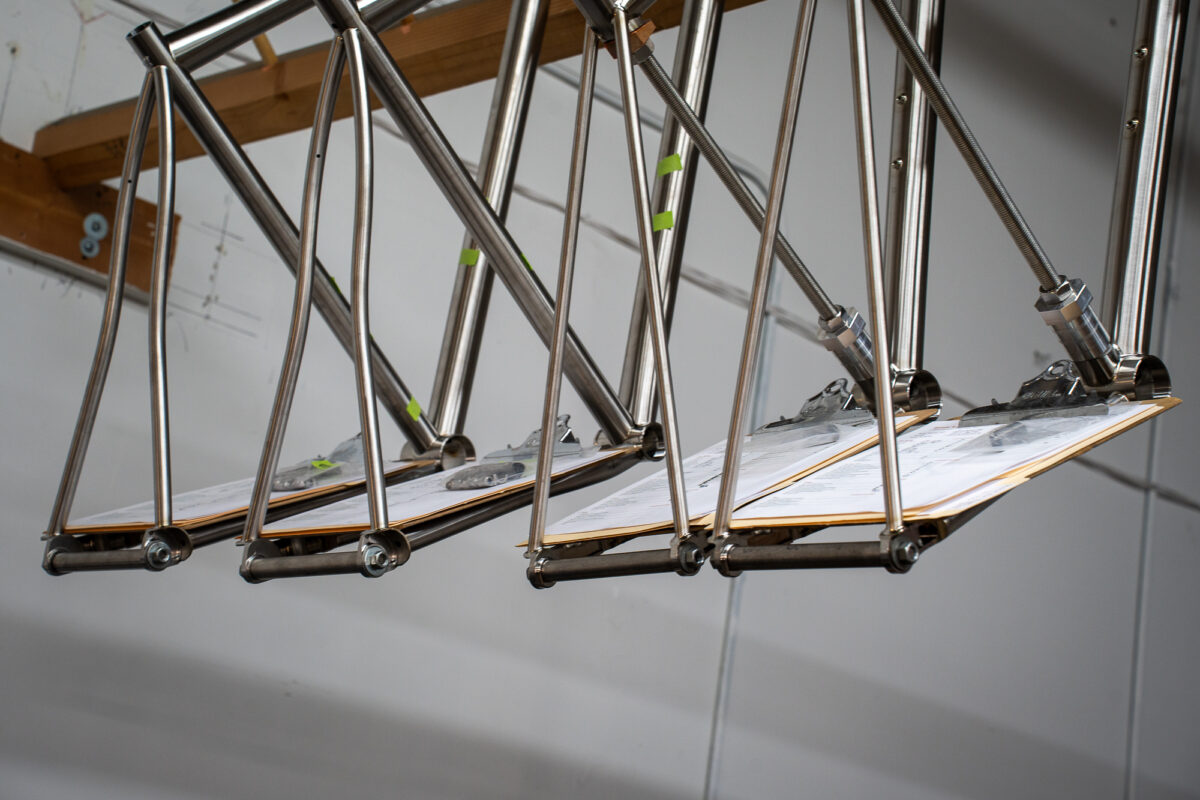

Walking through the various production stations, Barchek compared the process he has instilled at Mosaic as being akin to the restaurant industry’s mis en place system of ingredient organization: prep everything you can in advance, and keep it neat and close at hand. Each dish may be made-to-order, but keeping a tight mis en place streamlines the process. Barchek applies the same strategy to Mosaic’s bike-building program (“Don’t fuck with my mis,” he said, quoting Anthony Bourdain): when full-length titanium tubes arrive at Mosaic, most are cut down to workable sizes, and universal elements of frames—whether to be used for one of Mosaic’s batch-built models, or fully custom builds—like headtubes, and seatstays joined to rear dropouts, are batched out in advance. Beginning to assemble a frame, then, starts to loosely resemble going grocery shopping for ingredients, shopping for parts. But the proverbial “prep” work can only get you so far; it’s Mosaic’s craft that turns the raw materials into works of art.

Of course, the team at Mosaic is hardly cranking out frames; the company builds between 250 to 350 bikes depending on the year. These attempts at improved efficiency are meant to keep their margin for time and labor as tight as possible in a sector of the bike industry that is inherently time-consuming and meticulous.

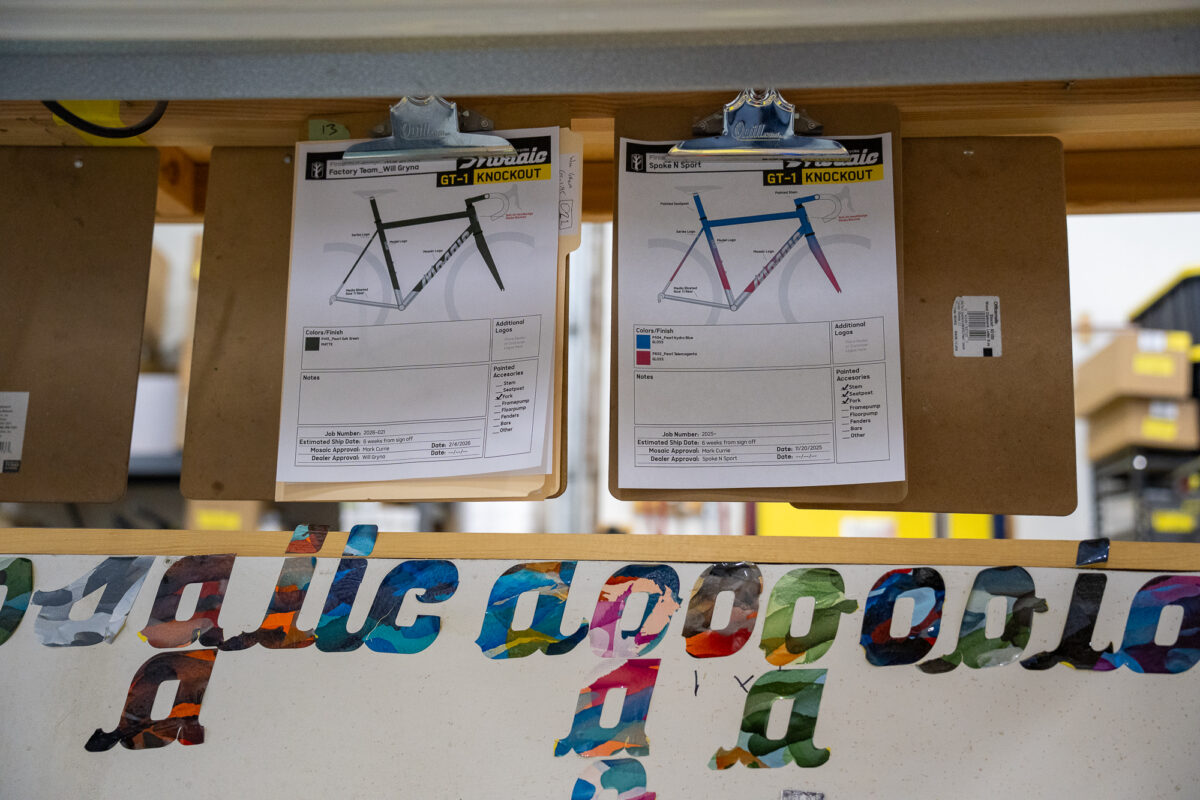

Once you know the code, Mosaic’s product line has a similarly efficient naming convention within its three main series: the G-Series, R-Series, and M-Series. You can probably guess that G, R, and M stand for gravel, road, and mountain bike, respectively. But for a product like the GT-2 AR, it’s helpful to know that the “T” stands for titanium (Mosaic formerly fabricated steel, so an “S” could have occupied this space in the past, but Barchek said that phased out during COVID when it was nearly impossible to source Columbus tubing), the “2” refers to straight-gauge tubing (a “1” here would refer to custom-butted), and the “AR” denotes Mosaic’s All-Road model that they nest beneath the gravel-category umbrella. Other product-name suffixes include “iTR” for integrated cockpit, “45” for 700 x 45 mm clearance, and, among the road frames, “d” for disc or “c” for cantilever.

A recently introduced disrupter to Mosaic’s series system is the new Zero Ops category, a venue for the brand to showcase experimental and exclusive limited-release models. Although Mosaic has done artist-collab finishwork projects in the past, RT Zero—a run of pre-ordered 25 performance titanium road bikes, designed around an in-house engineered D-shaped carbon seat mast and custom finished—is the brand’s first creative flex under this moniker. With an RT Zero costing more than in-state tuition at Mosaic’s hometown university, CU Boulder, Zero Ops is a decidedly ordering off-menu move.

Mosaic employs six full-time staff, three of whom work on the fabrication side of the building, and two of whom work on the Spectrum Paint & Powderworks side of the building (I know that 3 + 2 only equals 5, but we’ll meet Mark Currie, Mosaic’s head of Marketing and Sales a bit later). Mosaic acquired Spectrum in 2016 as a way to bring more control and creativity over its complete bikes, and the brand’s bespoke finishes—often balancing elaborate color detailing with the spare minimalism of the working material—have become one of its most defining aesthetic elements.

After getting the “medium-short” tour from Barchek on my recent Mosaic shop visit (which still entailed almost an hour of oogling), I wanted to sit down with the founder and his number two, the aforementioned Mark Currie, to chat more about Mosaic’s evolution, position in the cycling industry, and what might be next for the brand (spoiler alert: 32ers did enter the conversation).

A Q&A with Mosaic Cycles Founder Aaron Barchek and Mark Currie, Mosaic’s Head of Marketing and Sales

HM: You started Mosaic in 2009. What were you most excited about in bikes at that time?

AB: I think the angle I’ve always come to it from was two-fold: as an athlete, just really enjoying riding bikes, and as a maker and designer. So, that would have really excited me at the time [2009] to think that I could continue doing it, just making things. The enjoyment of doing something from start to finish, that you have your hands on the whole time. And if that also fills up the cup of making something that I can then also go out and ride and test in the real world or just enjoy, that would have been really, really rad. And so I’m sure that’s what kept me going or at least got me started.

HM: Talk to me about how the product line started—was it custom, everything? Were you specifically focused on the road side of things initially?

Mosaic founder Aaron Barchek

AB: I think when you start something at age 26, you don’t really have a handle on exactly what it’s gonna be. I think my guiding light was always that I just wanted to see it as a career and continue working towards that. At the time, road was super popular, certainly in Boulder. Cyclecross was super popular in Boulder. Coming from a background of working at another company, I had a wonderful education with great mentors at Dean, who taught me a lot from making stuff to just the experience of seeing how the bicycle industry worked and what was what was going on at the time.

It was a really interesting time. Handmade was in the mix, you know, it was very popular, but you have carbon bikes coming up at the same time. And I think where I slotted into that is, I wanted to present something that, in my mind at the time, was maybe fulfilling some of the things that handmade didn’t offer that I saw, in terms of turnaround and quality and just approachability, and a product that you could get access to in a bike shop.

I don’t mean to say any of that in a bad way. It was more just what I thought of what handmade could be. Or a part of it could be, at least. These are the early, early days of the North American Handmade Bicycle Show (NAHBS), and you go to Portland and it’s just crazy stuff all over the place and it’s all wonderful. But like, where do you go to get it? How do you get it? And does it take years to get? And my brain always thought, you know, handmade would be more popular if it could just be communicated better, or you could have a turnaround of, like, six or eight weeks, and reliability.

Mosaic head of Marketing & Sales, Mark Currie

MC: And more definitively attainable. To your question about where did the Mosaic product line start—I wasn’t a part of original Mosaic, I’ve only been here six years—but if you look way, way back in the archives, you will definitely notice a narrowing of the scope of what we do. Now, we define a product in a category and stick to it. But if you cruise back ten-plus years ago, you’re gonna find, like, a Mosaic dirt jumper. You’ll see things that you absolutely wouldn’t see us do present day but are an interesting way to kind of path that evolution.

AB: And that part of the story is so wrapped up in creative entrepreneurship and the journey of just going from saying, “I want to start something and do it,” to then finally figuring out how to do it. If you start something like that, there’s no way you can know exactly how to do it. That’s the fun part, ultimately. And a lot of what it’s taken us to get here is in the ethos of the business. That’s why we try to do the projects in-house. That’s why we do the marketing in-house.

In the search of making a business, right, that’s professional, and—let’s even say viable—to start off with, and then have that viability be sustainable, that was always my notion of what we wanted to accomplish. And in doing that you have to create jobs for people, and you have to create a lifestyle, and you have to create the brand that is in support of all of that. I also knew that I really wanted to work with people. I enjoy the collaboration of having a team. And so being a one-person show was probably not in the cards.

HM: When did you feel like the business could support other employees?

AB: Very soon, I almost don’t remember. It’s like the dark days of how did we do that? How did that happen? We had a few really early, early-day kind of intern people that turned into employee one and two and kind of came and went as the business grew and needed more talent and different talent. So it kind of went from one to two to three to four to now six. We would have more if we could.

HM: When did Mosaic start making gravel bikes and mountain bikes?

AB: We’ve always made mountain bikes. The first frame that we ever officially stamped was a mountain bike. 0001 was for Chris McNally. I believe it’s sitting on Facebook marketplace for sale right now. Well, it wasn’t the actual first frame that we made. There were probably a few other ones. But it was probably the first one that I just felt inclined to stamp. He called me up and asked for permission to sell it, and I was like, “Of course, dude. Like, it doesn’t matter to me.” That guy calls like every couple of years and is like, “You want to buy this?” And I’m like, “What am I gonna do with it?” Which is funny because I have been kind of collecting a few early bikes. Maybe we can crowdsource it [laughs].

MC: Number 0001, Mosaic Titanium mountain bike frame. $2000 bucks on a Pinkbike.

AB: Certified that is absolutely it. But, mountain bikes, it’s a smaller marketplace, especially for more expensive handmade stuff. So it’s always a portion of what we do. We ride a crap-ton of mountain bikes internally. But it’s definitely not the predominant thing that we sell.

Gravel bikes are funny because, like, when did that start? I don’t know. I moved to Colorado and on day one somebody literally told me to get my road bike tires dirty up in Ned[erland]. We rode our road bikes everywhere. I rode County Road 68 all the time on 25s. My recollection of gravel is somewhere around when Enve comes out with the gravel fork. We end up winning Best Gravel Bike the first year that was a category at NAHBS. I think that’s like 2016. That’s only 10 years ago. So that kind of coincides with flatmount as far as frame design. And so somewhere around—I don’t know, somebody’s going to factcheck me—like 2014, 2015 the word “gravel” starts getting used.

I mean, I can remember when the term “29er” started getting used and we were like “Bleh, 29er crap.” But we were definitely riding the crap out of cyclecross bikes. The addition of disc brakes to cross bikes, even just cable-pull disc brakes on crossbikes, I think opened up a lot of riding in the Boulder area that we were probably doing on road bikes, but then doing on, like, cantilever cyclecross bikes. And then disc brakes come along, we’re like, “These are sweet. How do we get these?”

HM: Given the prevalence of performance-focused carbon bikes, and the connotation around carbon as going fast, going light, what do you think people get wrong about titanium as a performance-focused material?

MC: To step back for a sec, most people probably haven’t had the chance to ride a titanium bike and form their own opinion on it. So they’re relying on whatever they’ve been fed. And there probably haven’t been that many performance-focused titanium stories that have wound up in front of people. So we’ve tried to do our part to tell some.

We sponsored an athlete, Brennen Wertz, who ended up winning elite Gravel Nationals [in 2024] on one of our bikes and who had a bunch of other success along the way. And those were fun auxiliary stories for us to tell. Look, I don’t really think our core customer is ever going to be the bike-racer type, but there’s an interesting auxiliary story to tell there. Like, if you’re somebody who wants to participate and race at a high level and perform, we do offer something that may be really compelling to you, especially if you’re somebody like a Brennen Wertz. Or, just having something that fits you properly might actually allow you to unlock a whole new level of comfort, performance, whatever it is.

HM: So leaning into the custom side of things rather than the material itself?

MC: That’s part of it. But I think for certain applications the material lends itself really naturally to that use-case, gravel being one of them. Gravel is a destructive sport. We were at Unbound a few years ago, and there were countless examples of people who came back from that with holes sawed through their seattubes and their seatstays. And, you know, fair enough we came back with some paint missing from our bikes, too. But we cleaned them off, repacked the bearings, kept riding them. We had another rider that same year, Kristen Legan, who won Unbound XL on a Mosaic. There was a lot of destruction in that particular race. And Kristen’s still riding that bike. So there’s a cool durability play there where you can do something right once, and continue to use it for years and years and years, for as long as that use-case and that spec are what you’re after.

HM: Aaron, you were starting to come up in the builders’s space when carbon was eclipsing metal. Tell me about that.

Aaron: Yeah, it was right when that was happening. I would say early 2000s was when it was still kind of like, “Is carbon happening?”

HM: It’s hard to imagine, now, there ever being a debate about “Is carbon happening.”

AB: Certainly in terms of cost-effectiveness it put many people on bikes that might not have otherwise been on bikes because you can produce it so efficiently. Does that happen with metal bikes? It’s not currently happening on that scale.

MC: I think, too, we’re never gonna pretend that we can build the lightest bike out there. You want the lightest bike? Buy an S-Works Aethos. You want the most aerodynamic bike? Go buy whatever that is, a Pinarello Dogma. But if you’re somebody who, like most people, don’t have the crazy luxury of having a race-day-only bike and then a bike to train on all the time, then what we can get right is [building] a bike that is 100% the right bike for you to ride all the time. So you train on it as much as you want then you race on it, and then you stack a whole bunch more miles on it training. And your perception of that is going to be so positive that that’s gonna be the bike you want to ride.

HM: What do you see as the benefits to manufacturing titanium frames in the US?

AB: I think the way that we design and fabricate, or choose to design and fabricate, bikes through a made-to-order process is always gonna get you to a better spot. Because most of what we do is making it specifically for you, the rider. Whereas with something that is coming out of a huge production facility, you’re just going to have heavier stock tubes and cheaper tubes and lesser-quality tubes. So, yeah, I think we can do it better. But that’s by choice. Right. It’s not that maybe others couldn’t be making that choice.

HM: Where does Mosaic source its tubing?

AB: All over the place these days. Most of the raw material is going to come out of China, or Asia at the very least; we get some of our stuff from Japan. And then we have some machinist partners in the States and overseas that do both tubing and machined components. For our new Zero Ops program, we had a company in Ogden, Utah, do the carbon components for us. So we get it all over the place, and then forks and stuff all come out of Asia as well.

HM: I feel like we’re in this time in the cycling industry where you always have to ask about before COVID and after COVID, because it was just this huge inflection point.

AB: It is, but I don’t know, when I started building frames it was maybe more of a thing that at least some of your material came from the States, and there’s just material for ti bikes that you do not find in the States anymore. It doesn’t exist for certain applications. Yeah, COVID was interesting.

HM: Did the COVID phenomenon change the way that Mosaic has decided to source materials or change anything fundamental to the process of building bikes here?

AB: Yes and no. No, it hasn’t changed our process at all. It’s still the same ethos of what we do, why we want to do it, and how we do it. Yes, it has changed some of the backend supply-chain stuff that we do, more in that it just forced us into operating in a slightly different way that I can’t really describe. The fallout of the price-raising and inflation was, and still is, the biggest challenge. That’s not unique to the bicycle industry, any small business is dealing with that right now.

HM: And then the T word…Tariffs?

AB: Well, since we have some brand partners that bring things in for us, we didn’t necessarily see a physical tariff bill, but we certainly saw price-raising across the board in the last few years. Which has been a challenge, for sure. And then some of the stuff we do source from overseas just has the same tariff that it always had. So, I mean, admittedly, for the type of manufacturing that we do, where we’re bringing in raw material, it affected us probably less than if we were a company that was bringing in a full bike that was in a box. That would be my understanding of how other companies have been affected. It was crazy though. We had our fair share of supply-chain disruptions during COVID that were immense challenges. And federal help to get through it all. Thankfully. And a lot of good things happened, and a lot of weird things happened. Thankful to still be doing it.

HM: Mark, you said you’ve been with the brand for six years. Can you give me a short background about your relationship with bikes and then also when you came onboard with Mosaic, because that must have been right before COVID?

AB: Good story! [Laughs]

MC: Yeah, right at the start of COVID, literally. How did I get to bikes? I’ve always been an athlete, I was a runner and ran into college and then decided that competitive running was too serious for me at the time, and I started racing bikes instead. And that has led to a whole lot of decisions in my life that put me here. I have a degree in finance, and six months out from graduation at CSU in Fort Collins I got pretty terrified about what that prospect looked like from a career perspective and immediately started looking for viable alternatives on how not to sit in, like, a J.P. Morgan cubical all day. Which is not all bad. There’s definitely an upside to that. I ended up going to work at Enve for a few years. And that’s where I made some really excellent friends and connections. At the time that I worked there, the OEM Sales Manager was a guy named Kolby Weber, who’s become one of my very best friends, who would have been the Mosaic Enve contact at the time. [Aaron interrupts: “Shoutout Kolby Weber!”] So a few years down the road he would introduce me to Aaron. And all throughout that I was always racing and training, mostly mountain bikes. That’s kind of been my thing up until the past sort of seven or eight years when gravel became interesting and then, road bikes became really interesting.

So I started here in the middle of March, 2020. Went to Mid South, the controversial one. Did that race in the mud, got super sick after it for those two weeks that I worked remotely at home. And then started coming into work every day, and Aaron and I just kept ourselves away from everybody else. In hindsight, there were some positives to that because all of our dealers were closed, so we kind of had this crazy, probably six-week period of very, very slow, nothing-going-on downtime here. Which ended up just being a crash course for me. So that probably got through the end of April or May, and that was when sales started to come in again and then just like ratchet up, up, up, up.

It’s fun because we’re a small team, so we get to wear a lot of hats. We sort of split product management, product design, all that, neither of us are mechanical engineers, Ross [a Mosaic welder] is, but we can usually conceptualize something pretty damn well for what we want it to do, and what we want it to look like. And then lean on other partners to help us and put that into fruition.

AB: I think since Mark has been on, we have basically replaced the entire model line with a newer iteration. We’ve done RT-1 iTR, GT-2x, MT-1, MT-2 and then some sneaky things that are coming up this year that I can’t tell you about..

HM: Today in 2026, how would you each define the brand tenants of Mosaic, from the design and fabrication side, but also from the marketing and storytelling side?

MC: The phrase we use a lot that I really like and have sort of continued to evolve the definition of when [Aaron] coined it is “the new American handmaid.” We want to design bikes that are fast, fun to ride; they’re aesthetically pleasing, and they have a modern touch to them. And I think our finishwork does a lot of that. Paint starts so many conversations for us. And you have to build a really good bike underneath that, but there are definitely people who walk across the street because they notice a painted bike. Titanium is a material of choice, but doing it in a really fresh, modern way, that’s probably reflective of the input that we have here. I think that shows the product.

AB: The only thing I would add to that would be whilst holding onto the roots of where it all came from. And the fact that that’s why we do it in-house, and that’s why we’re doing it by hand. And that’s why we’ve chosen to continue the work that we’re doing currently and we’re not making a 3D-printed aero road, titanium bike. I’m not saying we’ll never do that when the time is right. Maybe.

HM: Do you use any 3D-printed parts?

AB: No, currently no.

MC: We very intentionally worked around it on that RT-Zero project and used CNCed parts instead. Which goes right back to that preserving-where-it-came-from approach, traditional fabrication techniques. But you pair that with a really modern take on what our road bike is and that’s our RT-Zero bike.

To another part of an answer to your first question—where does Mosaic position itself as a brand?—I think the other unique thing would be our commercial strategy. We are focused on supporting our network of independent bike shops that we call dealers, and that currently represents our entire sales channel. And that puts us in a very unique spot. We sell almost 100% of our forecasts through our dealer base. Our customers, the people that I interact with, are through our dealers. So if you are whoever in Austin, Texas, and you want to buy a Mosaic, you might call me—

AB: And if you do, we will happily answer and bike nerd to the end of the day with you.

MC: But at the end of that conversation, what I’m gonna do is refer you back to one of our dealers to finalize that sale. And the reason for that is because when you are selling a product like we are, which naturally sits, no matter what, at the higher end of price point, even at the most accessible version of it, there’s a premium experience that we believe that our dealers can offer to anyone who’s making that purchase, that we simply couldn’t, by doing it all here. You know, walk in the door, sit down, do a bike fit, any of that sort of stuff. So it’s a much more personalized hands-on experience that our customers get throughout the whole process with their dealer. And by us committing to that strategy, we support the independent bike shop with really healthy wholesale margins to keep that segment of all industry alive. Not saying we’re doing that on our own but we’re certainly helping, And that’s not new. That’s a Mosaic process from day one.

And we’ve had some really incredible experiences with dealers and meeting some of these folks all over the world. We were in the Czech Republic, and I met a dealer who predates me here by at least six years, so they’ve worked with Mosaic twice as long as I have. And you know, then they invite 40 people to come and have lunch with us. We were just like “Whoa.” That right there, like that experience, validates the value of a dealer in any market. Because no way can we show up in the Czech Republic and say, “Hey guys, we’re here,” like nobody cares. Like, you’re not even gonna get that message out, you know? There’s no amount of advertising that we could put in front of somebody that would convince them to come and be a part of that, whereas the relationship they have with that dealer is the whole reason they show up and talk to us. And that’s just one example.

HM: About how many dealers does Mosaic work with?

MC: Our whole dealer list is probably somewhere in the 60s. Of those, I would say active dealers that we can really forecast on are probably more like 25, 30 that are consistently working with us. Like small, expert-run shops and studios. Above Category is a perfect example—those guys smash. They’ve been very near number one as a Mosaic partner for a long time. And there’s other great examples too: Velosmith in Chicago, The Bicycle Café in Prague, Bespoke in London, they’re all over the place.

HM: Something that you said when you were showing me around, Aaron, that I thought was really interesting, is that Mosaic has, in recent years, struggled more with the mid pricepoint, specifically with your batch-build tier bikes. What do you think contributes to that?

AB: There’s a really complex answer to that. I think it’s always wrapped up in anything that’s made on a small scale and certainly by hand, as a viable, sustainable business is going to be a more expensive product. So there’s just always going to be a price piece associated with that conversation. Not everybody can afford a $10,000 bike, let alone a $7,500 bike. And things have just gotten more expensive across the board. We’re not the only brand guilty of that, Specialized has gone up the same way that Mosaic has gone up, as well as just cost of living and inflation and the economy vibes.

We were talking about this delineation between made-to-order and batch-built. Made-to-order is the custom program and we’re making it specifically for you. We’re also probably guilty about highlighting that a lot, especially lately since we’ve released the RT Zero through the Zero Ops program, and we’ve had numerous super successful artist series bikes come out. It’s the thing that we’re gravitated to, and so it’s the thing we pour our energy into. And it’s the thing we tend to show off the most.

So you don’t hear about our batch-built program a whole lot, that you can still get a really, really quality handmade bicycle by the same people with the same material, for, at this point, like half of what the cost of a made-to-order frame is. I think our batch-built frames are around $4,500 for a frame and fork in a raw finish, and we might have some changes coming to that this year. You could build up a mosaic, probably—don’t quote me on this—for around $7,500? Is that expensive? Yes. Is it a really great value? I think so. Would I like to put more people on Mosaic in that realm? Yes, absolutely.

MC: We’ve actually had a bunch of long conversations about certain things we’re gonna do this year where we might very intentionally focus on that product, our batch-built bikes.

AB: And we’re all coming to it from a point where we’re those makers, and we want our product to be accessible, and maybe we think it’s more accessible than it probably is. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t keep talking about it.

MC: There has also been some pretty compelling competition pop up in that stock titanium realm. Some of it might be made here, some of it definitely isn’t. But that’s probably the most competitive space that we could be in. Whereas you look at our made-to-order bikes, we’ve carved out more of a unique value proposition there and a segment of the market for somebody who wants that.

HM: Which category of bike does Mosaic sell the most of?

AB: It’s a strikingly even split. It’s almost like one-third, one-third, one-third [between Road, All-Road, and Gravel], and then 5-10% mountain bikes. More mountain bikes now that we launched MT-2 a few years ago. Hardtails are still cool.

HM: Well, if the units sold aren’t exactly forecasting things to come, what are the vibes telling you guys? Has gravel jumped the shark? What feels like the most exciting thing in bikes to you right now?

AB: Man, so many things are exciting to me about bikes, always. You look at the Mosaic forecast and I think it’s endemic of how people are just riding in so many different ways, it’s like becoming homogenous, to some extent. Road bikes are all-road bikes, all-road bikes are gravel bikes. I’ll underbike my road bike like a gravel bike. And I would imagine that continues to keep gravel growing, but there’s still so many roadies out there who haven’t even found a gravel bike. All you have to do is touch into any gravel race scene and there’s thousands of people coming out. Is that tapped now? No, not at all. Are we still gonna come up with more slim ways to define this bike as this type of gravel bike and this type of road bike? Yes, that’s gonna happen.

MC: Yeah if you look cyclically, we launched a badass new road bike last year, we’ll probably look at some off-road bikes this year. Some of those might have that Zero Ops kind of treatment. Others definitely won’t.

AB: And yes, we’re making a prototype 32-inch, on or off the record, I don’t care if you print that. It’s part of the fun of what we do.

MC: And it’d be nice to be able to form our own opinions on it.

AB: Last year, I had some component people call up to ask “Could you make a prototype 32er?” and I was like, “Fuck no.” [Laughs] I’m not getting on that right now. And then this year it started popping up in so many different places that it seems like it could be a category that the handmade community could do really well off of, initially. Because I think it’ll inevitably take—and I know companies have already worked on this and might already have their answers—but it’ll take a while to figure out where it sits best, if at all. And the product evolution to even test it out for like forces and what are the frames’ geometry?

MC: But it really remains to be seen if it even works for anyone under, like, 6’ tall without fully sacrificing how a good-riding bike handles. If you want a bike that—and I can eat my words—but it seems to me that if you’re under 6’ and you go to 32-inch wheels, if you don’t want, like, midfoot overlap, you’re gonna have to just have a bike that rides like trash and doesn’t not want to turn.

AB: Admittedly, I haven’t been riding my gravel bike a whole lot in the past couple years. It’s almost become a tool that I just bring out to race on. And I kind of see that as the 32er if there’s anything, for me, that it could be. It would be the thing that I would bring out for the week before a race the same way that I’m gonna use my full suspension bike for this race, and I’m gonna use my hardtail for this race. Two different tools, but they have their own place. So who knows what 32 does. Let’s just put it out there and see. We got a couple [prototypes] that we’re working on this month, and the hope is to do a couple different geos and, ideally, get a smaller rider on one, too. I’m 6’2”, it’s probably gonna work just fine for me. Maybe I don’t have enough difference to really say that it’s a good or not a good thing. Companies like us that can potentially be more flexible around it and maybe test it out earlier, that harkens back to the old handmade days where R&D was really coming out of fast replication. The iterative process that you can’t necessarily do in a carbon mold, but you can certainly do tube-to-tube construction things really quickly. So, we’ll let you know.