The match referee and the umpires who officiated the Lord’s Test are facing an avalanche of abuse from English ex-players (including ex-captains), journalists, podcasters and content creators after it was announced by the ICC that England had been docked points for a slow over-rate in the Lord’s Test, while India had not. Most of this abuse is of the worst, most insiduous kind. It alludes to, implies or suggests that their decision is obviously inexplicable and therefore their competence (or worse, their integrity) is suspect. Pointing out that this amounts ot abusing the referee and the umpires will probably be considered rude. But “I haven’t read the rule, but the decision feels wrong, so I’m simply questioning the motives or competence of the people who worked out the decision” is abuse. It is the bad faith logic of the flat-earthers and other denialists. There is no word for it which is more accurate.

The over-rate rule is published, and free to read. None of these journalists, podcasters or content creators have bothered to read it. I’ve even had conversations with podcasters whose podcasts many of you may listen to, who (a) haven’t read the rule, (b) misread the rule after I share it with them, and then (c) say that the rule is “as clear as mud” when it is explained to them. Others point to sources and link to articles from 2023, even though the playing conditions are updated regularly and the updated versions are published on the ICC’s website. The persistent, wilful ignorance of the existence of these published rules is typically dressed up with good intentions. “We’re just trying to improve the game”.

It just doesn’t wash. People who can’t be bothered to read and seem to be ruled by their partisan preoccupations and resentments are unlikely to want to improve anything. Most of these people don’t realize that they’re being abusive because they’re floating about in a lukewarm secondhand soup of third rate interpretations and nostalgia (“they used to bowl 21 overs an hour in the 1950s!”, “everyone agrees that modern over-rates are outrageous/abysmal/shocking[or some other incendiary term implying malice]!!”). They go through this ritual of rage, abuse and content creation every time there’s even a whiff of an opportunity to discuss over-rates. The one thing they never ever ever do is read the rule. One variant used by the set of culprits listed above is to reluctantly skim the rules when they can no longer be ignored and treat them as an a la carte menu from and point to stray phrases which they insist either support their view or suggest some fatal contradiction in the internal logic of the rules. None of them seem to care enough about cricket to actually study the rules which govern it.

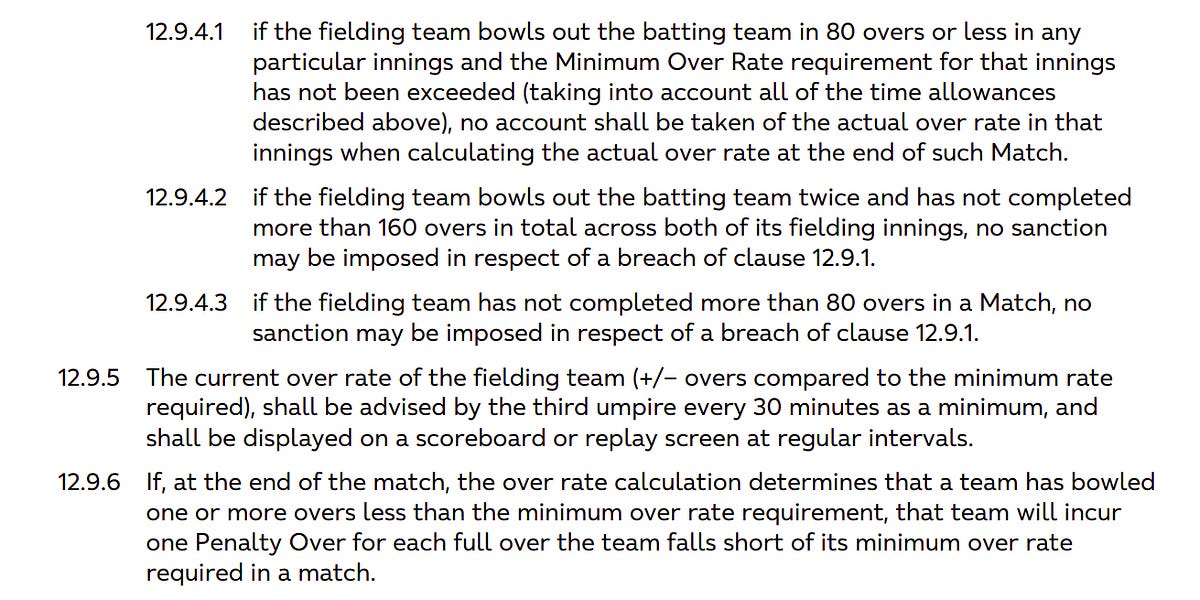

The rules which govern how the over-rate is to be calculated are published in the Test Match Playing Conditions [pdf, p. 31, a screenshot is attached at the end].

Anyway, this persistent ignorance is unlikely to change. Persistent ignorance is certainly not an exclusively English strongpoint either. Just in the Lord’s Test, replace English with Indian in above paragraphs, and replace over-rates with ball-tracking, and you will get a perfectly clear picture of the abuse hurled at Umpire Reiffel by Indian ex-players, journalists, podcasters and content creators. The word abuse is exactly equally apposite in this case as well.

Now, to the publicly available data. This data is exactly equally available to me, you and everyone mentioned above. Apart from the rules, Cricinfo’s scorecard provides the length of each individual innings in minutes (see the column “M” in the spreadsheet). The total playing time for a team innings is the sum of the minutes batted by each player in the innings divided by two (since there are two batters, one at each end). Applying this to the Lord’s Test we get:

1st Innings: 675 legal deliveries in 522 minutes.

2nd: 716, 556

3rd: 373, 277

4th: 449, 365

The over rate calculation includes allowances for each wicket (2 minutes) and each drinks break (4 minutes). Additionally the bowling side also receives allowances, measured in terms of the actual time lost, for onfield injury treatment, DRS reviews, time-wasting by the batting side, and any other time lost for reasons which are beyond the control of the fielding side. If a wicket falls on the last ball before a drinks break or a session break, there is no fixed allowance for such a wicket.

In addition to providing the minutes batted by each batter, the scorecard provided by Cricinfo also gives a summary of scores at each drinks break and each session. So it is possible to calculate at least the fixed allowances for each innings with complete accuracy. For instance, one Day One, there were 4 wickets and 3 drinks breaks – 20 minutes in total. Further, there was one DRS review. Additionally, there may have been deductions for time-wasting, injury treatments etc. In this way, estimating the approximate over-rate is a fairly straightforward calculation (It is little more than a 4th grade arithmetic word problem).

The 1st innings of the Lord’s Test includes 18 minutes for 9 wickets (since the 10th ended the innings) and 12 minutes for three drinks breaks. Deducting 30 minutes from 522, we get 1.37 balls per minute for this innings, or 13.7 overs per hour (675 legal deliveries in at the most 492 minutes). Additionally, there were two reviews, plus injury breaks if any. So the over-rate for the first innings was at least 13.7 over per hour. For example, if one considers that all other deductions for reviews, injuries etc. amounted to 10 minutes in total, then the over rate – 675 balls in 482 minutes, is 14.0 overs per hour.

In India’s 2nd bowling innings in the match (the third of the match), there were 4 DRS reviews, 8 wickets for which the 2 minute allowance counted (England’s second wicket fell the ball before the first drinks break on Day 4), and 2 drinks breaks. That’s 24 minutes of fixed allowances, in addition to the DRS reviews and injury breaks (for Crawley etc.). Considering just the fixed allowances, India’s over-rate for their 2nd bowling innings comes to 14.7 overs per hour. Even if you consider just 6 extra minutes for the 4 DRS reviews, time wasting and injury breaks combined (this is a very very low estimate), this over-rate creeps above 15.0 over per hour for this innings. This is important in this instance.

The over-rate for each team is evaluated for the whole match, and not for a single innings. A team has to achieve the required over-rate over both innings. The rule (see 12.9.4) makes three further allowances. First, if a fielding side bowls the opposition out in 80 overs or less, and “the Minimum Over Rate requirement for that innings has not been exceeded”, then the team’s over-rate for that innings is not included in the over-rate calculation for that team for the match. If the Minimum Over Rate requirement has been exceeded, then it is included in the match over rate calculation for the team.

There are two more allowances (12.9.4.2, and 12.9.4.3) which are self-evident extensions of 12.9.4.1. But 12.9.4.1 is designed to minimize the damage to teams which might have a slow overate because (for example), they bowl more fast bowling and less spin. Without 12.9.4.1, England’s penalty for the Lord’s Test would likely have been harsher than it actually was.

In the Lord’s Test, England’s over-rate in the 4th innings was slower than their over-rate in the 2nd. Given the allowances specified in the rules, it was unlikely to have exceeded the minimum over rate requirement. So England’s match over rate was almost certainly only their over rate for the first innings. For India, their 3rd innings over-rate almost certainly exceeded the minimum over-rate requirement. So it would be included in their match calculation (and was evidently sufficient to overcome their slow over-rate in the first innings).

The publicly available record, when considered properly, shows that the over rate ruling by the referee is reasonable.

Given that it is possible to examine all this merely by spending 20 minutes or so studying the public and free record available with a few taps on your keyboard or phone (and some arithmetic which a 10 year old can do), insinuating that the referee and the umpires by insinuating that you don’t understand how they could have reached the conclusions they did (as so many journalists, podcasters, content creators and ex-players have done in the last couple of days), is abuse. These people have abused the referee and the umpires. They owe them an apology. This is unlikely, so at the very least, these abusers owe cricket fans their silence. This alas, is also unlikely.

Hence this quick calculation and this lament. It is not pleasant to have to point out things like this. The over-rate is one of the most boring pseudo-issues in the game in my view. But as a device for undermining the authority of the umpires and cultivating the partisan resentments of a target audience (as most of these podcasters, content creators, ex-players and ex-captains aspire to do), it is lethal.