Chipps explores a different way to take the uplift for a day’s riding in the Pyrenees

Words & photos Chipps

Hey, this feature looks even better when viewed via Pocketmags; you get the full graphic designed layout on your device FOR FREE! It’s not quite as beautiful as the paper magazine.

I think it’s pretty common to look around at the uplift vehicle you’re in and wonder, suspiciously, how old it is and how many miles it has on the clock. After all, some of those Transits and Land Rovers have done a few journeys.

Today’s uplift system is over 100 years old and, while a little creaky, is still doing an excellent job of ferrying passengers from the lowlands up a rocky Pyrenean valley to 1,500m and beyond, almost to the Spanish border. Mind you, most uplifts take ten minutes or less. This is more like an hour and a half, but the tourists pay just to do it – and the descent is worth it. The views aren’t bad either.

Ride the canary

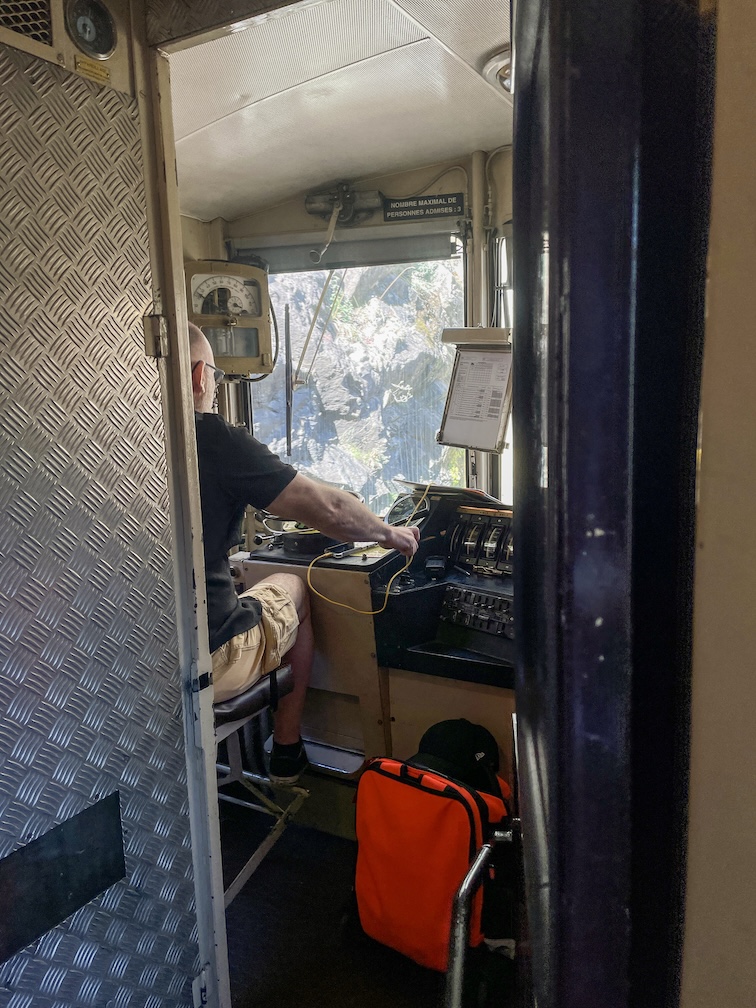

We’re on Occitanie’s Little Yellow Train in the Pyrenees-Orientales, a 100+ year-old electric train that ferries tourists, skiers and the occasional commuter from near sea level all the way up to the high plateau of the Cerdagne, at around 1,500m.

Although I’ve done this ride several times, my regular companion on every occasion has been Régis Terrieu, my riding buddy here in the mountains. Unlike the excited, camera-toting tourists on the train, he seems unfazed by the epic mountain scenery and the truly impressive tunnels and bridges that make this journey (complete with our bikes in the guard’s van) possible. That’s because his day job is to work for France’s SNCF train company, and he’s the chief train controller at Villefranche-de-Conflent at the bottom of the hill and, therefore, often responsible for the ‘Le Train Jaune’ itself. So, in the 20-odd years he’s been working here, he’s done just about every job possible on the train in that time: driving it, taking tickets, and the great job of knocking icicles off tunnel entrances with a shovel while standing on the front of the first train of a winter’s day.

However, when it comes to the ride ahead, he’s as excited as the tourists. In terms of terrain, it cuts a literal cross-section through the riding in this part of the Pyrenees and always serves as a ‘best of’ the riding here. Starting with the high evergreen forests and anaemic-looking grassy plains that spend most winters under snow, then traversing high open meadows before crossing over to the south-facing bedrock of the region, this ride is a great test of bike handling, traction and endurance over 45km. And even though we’re cheating with an uplift, we’ll still clock up a vertical kilometre of climbing on the way back down.

Just ignore the brewery…

Coming out of the station at La Cabanasse, past the slightly bemused summer tourists, we have a number of options for the descent back home, as there are singletrack routes to the north and south of the valley that follow both the train line and the main road. Choosing to head south to the village ski station, we have an easy few kilometres on a back road. It’s just steep enough to remind us that, at 1,500m, we’re just at the height that altitude starts to tap you on the shoulder if you do anything too strenuous. Keep things smooth and spinning, though, and it’s not an issue.

At this point, we’re the closest we’re going to be to Spain all day, as the random Spanish enclave of Llivia is a mere 15km up the road, but we’ll be turning our backs on that and heading into French France for the morning.

At Saint-Pierre-dels-Forcats, things start to look familiar for anyone who’s taken a trip with Altitude Adventures, the guiding company run by Ian and Angela Pendry, as this was their base for years – only now their bike guiding business has been superseded by their beer brewery and distillery. While it’s tempting to stop for a pint and a chat, that’ll ruin things for the rest of the day.

As it is, at the village ski station, we choose the extra loop option of a half-hour gravel climb that puts us at the top of the Cambre d’Aze ski station. (We did once check the prices of the summer-running lift to skip the climb, but at €13 a ride, we figured riding for 30 minutes was the easier option.)

From Cambre d’Aze, there are a half-dozen or more officially marked enduro trails cut into the woods. Very natural in feel, the roots and exposed boulders would make any Golfie-fan feel at home. They’re hard to ride fast ’n’ smooth, and the morning dew makes the roots a little slick and unpredictable, but it’s a great extra loop to start the day with, and a complete contrast to the trails that we’ll be riding later. The shaded woods and cool air are a world away from the south-facing, bleached bedrock trails we’ll be on in a couple of hours. In a perfect metaphor for the feel of the earthy, pine-needly nature of the terrain, we pass perhaps a dozen mushroom hunters, wicker baskets bulging with porcini and chanterelle mushrooms.

Buzzy roots/rooty buzz

Back near the base of the ski station where we started, buzzing after the rooty goodness, our local knowledge kicks in as we take the fire roads above the little village of Planès. On a nondescript fire road corner, a tiny trail leads deeper into the woods on some perfect foot-wide woodland singletrack. It’s said that this was built to give the local enduro pro riders a better taste of the Scottish EWS singletrack, and our visiting Scottish pals confirm the likeness.

We emerge from the woods to some striking views over the valley. We can just see the top of the railway suspension bridge (apparently the only one in France) that we had crossed a couple of hours ago, but our attention is caught by the cypress trees of the little village of Prats-Balaguer, seemingly close, but actually across a deep gorge – and one that we’ll be descending into – down the ‘Ridge of Doom’ – a trail that cast fear into me on early 26in ventures when I first rode here a dozen or more years ago. Even on a modern trail bike, it needs some skills and a solid line choice to get down unscathed.

As we get onto more rideable terrain, we exit the woods almost into the middle of a load of half-naked bathers. While we were prepared for this, I’m not sure that the bathers at the Bains-de-Saint-Thomas were expecting to see mountain bikers appearing next to their hot spring pools.

Luckily for all involved, we were soon on our way – past the tempting-smelling (i.e. fried) snack shop – and onto more singletrack of a different flavour. As it’s a reasonably well-used path for walkers from one of the lower Train Jaune stations to the swimming baths, this is tight, but on the correct side of fun and doable, popping us out into the village of Fontpédrouse. While this is advertised as the train station stop for the sulphur-soaked baths, it’s a good 3km walk from the station, so not ideal if you’re just in Speedos and flip-flops.

Stocking up on the good stuff

Fontpédrouse is the aptly named fountain-based last stop to fill up on water before we cross the Yellow Train line on our way over to the south-facing slopes of the Têt Valley. Here, we get to see a lot more of the train and its fantastic architecture, sharing the valley with the river and the main road from Perpignan to Andorra.

On the five-kilometre climb that follows, it’s traditional for things to get a little quiet, as the ‘long time since breakfast’ and heat of the day feelings make themselves known. The broken-down singletrack road doesn’t particularly lead anywhere for anyone else, so it’s a good time for riders to cruise at their own pace, stop in the shade or search in bags for the legendary lost packet of Haribo. Even none-more-so French Régis, who prefers his trail snacks to be based on ‘real’ food, will soften here at the thought of a mid-Train Jaune Haribo.

It’s at this point that shoes are tightened, pads donned if you have them, and gloves are definitely on, as the next section is textbook, sticky-out bedrock. My not-even-O-level geology won’t let me guess at its true make-up: schist perhaps? As that’s what the local vineyards claim influence of, but ‘unforgiving, sharp and scratchy rock’ would probably cover it.

The descent that follows is a fully immersive experience where, although you’re somewhat aware of the vast valley near your right elbow, you only have time for the undulations of the trail ahead. And, although it would take a particularly athletic and airborne crash to send you off the hillside and onto the road far below, it constantly niggles at your nerves. Luckily, an overlook halfway down provides a rest for brake pads and pumped arms before you carry on again to the tiny village of Canaveilles, a half-dozen road switchbacks up from the valley floor. It’s here we can often catch a glimpse of a little yellow train, far below, full of unsuspecting travellers staring up at the ‘empty’ cliff face opposite. We’re not done yet, and though the trail does back off half a notch after this, by now, trail fatigue and the thought of a cold beer in Olette at the bottom of the descent can cloud your actions a little.

Still with that sense of some open air on your right-hand side, the balcony trail finally dips to drop you, unceremoniously, back onto the Route Nationale 116 on the edge of Olette. Luckily, the village is used to cyclists (the Tour de France whizzed through in 2021, and it’s often on the Trans Pyrenees route), so the sight of sweaty, thirsty riders at the bar doesn’t faze the cheery bartenders.

Don’t get cocky, kid

While the temptation to stay here for the rest of the afternoon is strong, we’re conscious that the ice cream parlour in Villefranche is going to be open until at least 5pm. In addition, Régis reminds me of a mutual friend who rode down the steps from the bar to the Yellow Train station here. Having survived the day of off-road descending, a moment of inattention saw him leave Olette in an ambulance with two broken wrists.

We cap things at a respectful single celebratory beer and take to the main road for a couple of kms, before a locals’ shortcut takes us past the mushroom farm and the ‘Bastides d’Olette’ – the ancient gates and threshold for these oft-fought-over Catalan borderlands between France and Spain.

Once off the main road, we parallel and cross the Yellow Train line a half-dozen times on our back road, as the little village roads fight for space with the metre-wide track of the trainline. It’s all very French and ‘safety third’ with a complete lack of gates and lights at any of the level crossings. It’s just assumed that you’ll look for the train before crossing, and, to be honest, you’ll hear it coming a mile off, as it rattles and hums with the kind of creaks that only old and worn-in things can.

Sixty flavours

A final half mile of main road and a last level crossing (with a gate and lights this time) brings us back into the world of noise and traffic, and we’re soon in the UNESCO Heritage village of Villefranche-de-Conflent; a medieval, Vauban-walled village of 200-odd folks that offers the usual selection of fridge magnet shops and leather and pottery workshops as well as a selection of cafés, bars and an astounding ice cream shop in La Chocoline. If you’re there in the winter, he might only have one, three-by-eight, flavour freezer (so, around 24 ice creams and sorbets) of home-made ices going, but if you’re there midsummer, there are four full freezers on offer. And at a mere €5 a double scoop cornet (in a super touristy village), you’ve more than earned it.

Trainfathers

I’m sure that the original thoughts of the Train Jaune planners didn’t have mountain bike uplifts in mind when they laid out their plans over a hundred years ago, but they happened to have cut a line that goes up to start at some great mountain biking, through some great mountain biking, to finish at some great mountain biking – with added ice cream.

The other thing to note about the average trip on the Yellow Train is that, in addition to the nonchalance of the train staff at having to fit a few bikes in the guard’s van, is the absolute lack of riders you’re going to encounter. For a tourist staple in a tourist area, the sheer scale of the countryside makes it easy to hide any mountain bikers who might be here. And if, on the off-chance you happen to be sharing the Yellow Train with another rider, it might just be the Train Controller, Régis.

Yellow Train how-to

Le Petit Train Jaune, or the Little Yellow Train, is a well-known feature down here in southern France, at the eastern end of the Pyrenees mountain range. It was built over 100 years ago as a way for the residents of the Cerdagne plateau to access the bright city lights (and jobs) of Perpignan on the Mediterranean, as well as the lands beyond.

Due to the massively steep cliffs and steeply climbing railway, it’s quite a marvel of civil engineering and was one of the first mountain trains not to need a funicular geared track to get up the mountain. The fully electric train line is powered by hydroelectric power, thanks again to the steep mountains that surround it.

The 63km line includes France’s highest station, at Bolquère (1,593m) and ends at Latour-de-Carol in the mountains, where, amazingly, you can catch (or alight from) a sleeper train to Paris.

A ticket to La Cabanasse is about €12 from Villefranche-de-Conflent, and bikes go for free – assuming there’s room in the guard’s van, so arrive a little early and get them sorted first.