Ben Shelton saved three championship points to defeat Taylor Fritz 3/6 6/3 7/5 in the final of the Dallas Open on Sunday. Shelton now leads the H2H 2-1.

While Fritz and Shelton are similar in their pedigree — big-bodied, big-serving Americans with forehand +1 firepower — it was their differences that were made stark in the opening games. Fritz’s serve was untouchably precise, whereas Shelton’s lack of precision was sometimes rendered to mincemeat for the compact Fritz backhand. In this instance, Shelton’s serve +1 was really Fritz’s return +1:

Shelton’s serve is a biomechanical thing of beauty. The legs, spine, and arms are all coiled with cobra-striking efficiency, able to inject wicked kick or bullet-train speeds:

But the motion exceeds the results, for the time being. Roddick often talks about the art of “pitching a game” when it comes to serving: how well can you select and vary your spots? how well can you hit them? how well can you disguise them? All these questions often trump ‘how hard can you hit it?’

Over the last 52 weeks, TennisViz and Courtside Advantage have shown Fritz’s first-serve (mechanically very good in its own right) averaged 51.6cm from the lines, whereas Shelton only averaged 64cm, well below the tour average of 59.8cm. This is part of the reason Fritz’s serve is rated 5th on tour, edging out the more powerful Shelton at 7th.

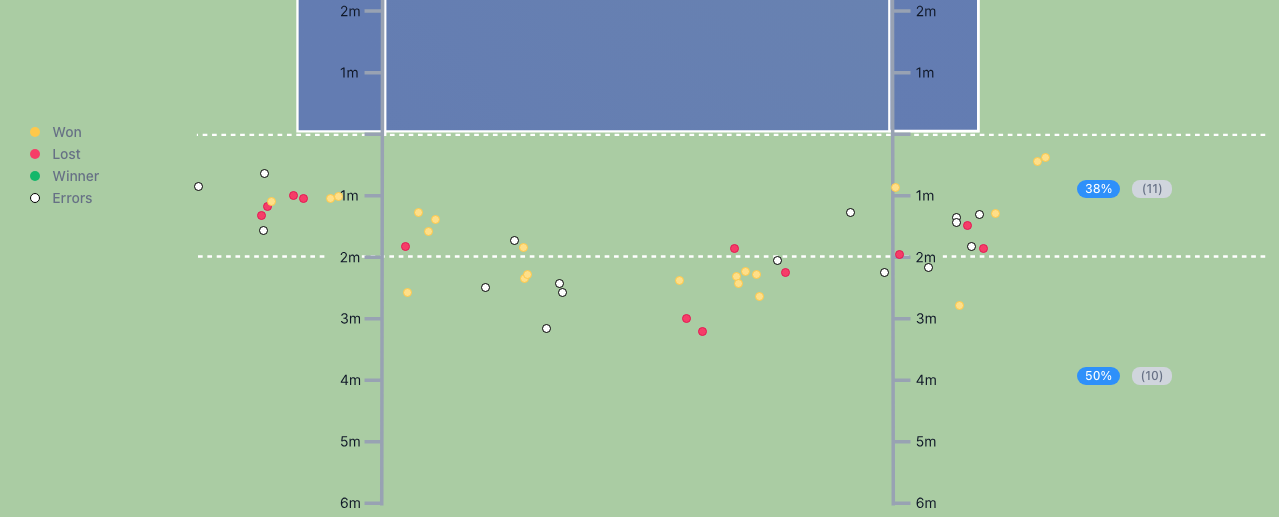

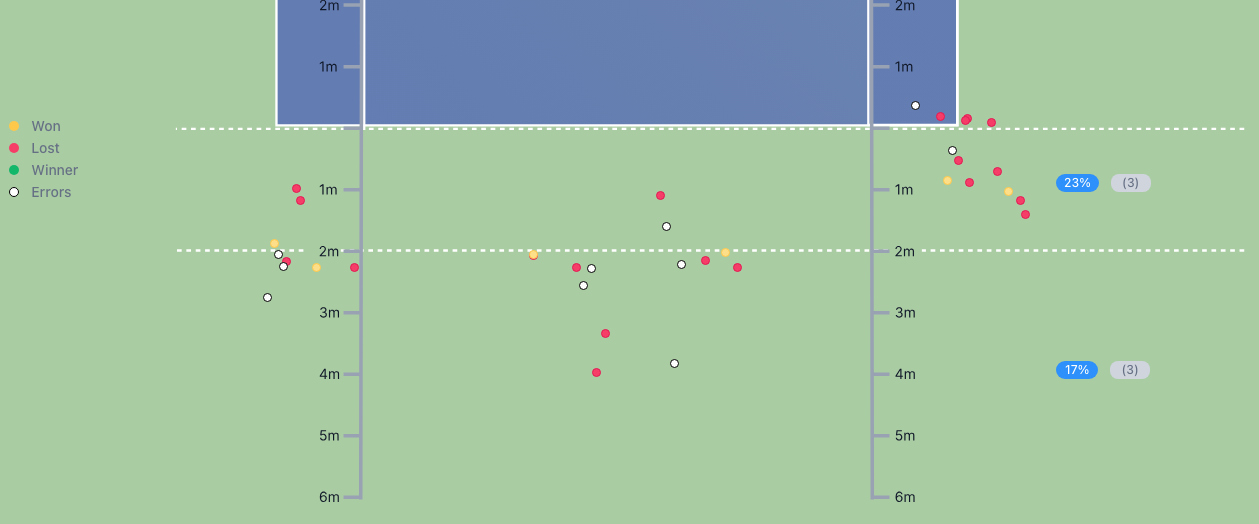

Compounding these differences is also the fact that Fritz is a more technically proficient returner. He is more compact off both wings, and was able to win a healthy percentage of return points while returning closer to the baseline:

Compare to Shelton’s measles-spread chart:

Shelton won Toronto last year (he beat Fritz in the semis) adopting a deep position on return and playing a Kirkland brand version of young Nadal on hardcourts: chipping, scampering, lassoing forehands on the hop, squash shot defence near obscure insurance sponsors. This, remember?

And it worked.

His return rating for that week was up to a 7.1 (good enough for 15th in terms of the field), and his steal score — a measure of how often players win a point from a defensive position — was way up to 34% (his average is 29%).

But near the end of that piece, I questioned whether such a strategy was going to help Shelton ultimately beat the top players, or if it will only ever work in the 500 and 250 events against the non-freaks:

He’s essentially running the peak Medvedev playbook here: serve big and play in-attack behind your own pitch, then knuckle down and build pressure after a quick hold. Andy Roddick used to talk about trying to make his service games feel quick — minimal routine, bang down aces, and put the balls in the other guys pockets — then fight tooth and nail to draw out the opponents return games with a more defensive and patient baseline game. I like the idea, but I’m just not sure this is where Shelton makes up ground against the elite competition that have stopped him in slams recently (Sinner and Alcaraz).

…I want to see Shelton lean into his variety and instinctive game closer to the net. I think he is very athletic, but less in a “let’s run side-to-side for 10 balls kind of way”, and more in a “let’s crush the ball and get forward, lunge at a volley, and mince an overhead” way.

Less Daniil Medvedev, more Jan-Lennard Struff.

Despite Shelton’s win on Sunday, I kind of feel the same. He’s winning battles, but is he taking steps to win a grand slam war against a Sincaraz?

One wrinkle in the Shelton baseline game is his backhand footwork when pushed wide. He nearly always hits it as a running crossover, wasting recovery time and reducing his ability to hit it hard:

I don’t know if I am simply looking for it more now, or if it is actually happening more, but I see signs that Shelton is sometimes employing strong open-stanced replies when pushed wide on that wing, I just want to see it way more:

A comparison of his usual crossover-step footwork (left) with a more modern open-stanced play (right):

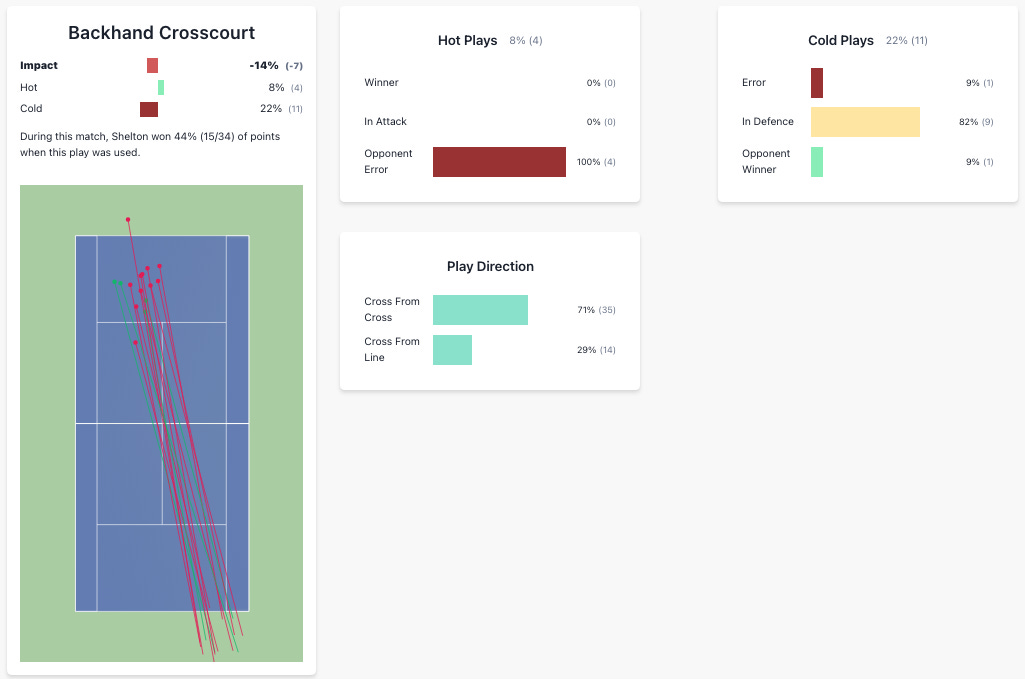

But it’s still a work in progress. The worst play on the court tonight was the Shelton backhand crosscourt. It had a -14% impact (which takes “hot” or winning plays, and minuses “cold” plays). If we take a look at the spray chart, the location is quite central, and the stats show that Shelton was often playing defence after hitting it.

You can sympathise why he plays it more centrally. It makes it a little harder for his opponents to direct their next shot crosscourt back into his backhand again, but at the same time, it’s not pressuring Fritz to move out of the centre of the court at all, and that with his reliable forehand, no less.

What I thought was good on that wing is when Shelton can get his foot and body weight moving through the ball. That’s when he was able to actually rush Fritz into errors or short balls, and he did it twice in the 1-1 game in the third set to break serve:

Here’s an example from earlier where Ben was able to rush Fritz.

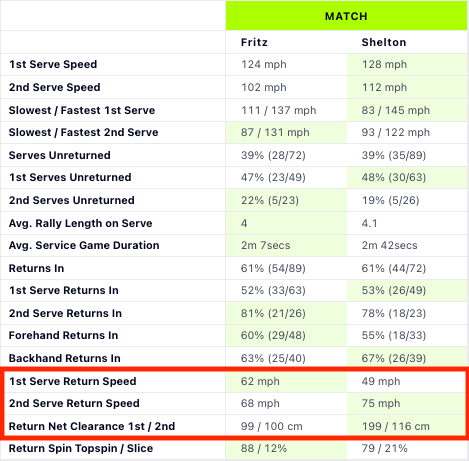

From Fritz’s end of the court, it’s hard to fault his strategy. His serve and forehand were utterly dominant and he was the better player for most of this match. He won 88% of his first-serve points to Shelton’s 71%, partly due to more accurate serving — especially in the first set — and partly due to Ben’s lack of first-serve return proficiency; Fritz got to dine on blocked and higher returns:

But those same blocked and higher balls did reveal my one major criticism of the older American, which has been a consistent theme: he lets players get away with chipped junk way too much (Musetti quarterfinal at Wimbledon, anyone?). Nowhere was it more evident than at 5-5 0-15 in the final set:

Actually, scrap that. The opening point of the very next game — Fritz’s last stand — was another textbook example of this net allergy holding him back from evolving as a player. You can’t hit the forehand better than that, but you wouldn’t need to if you could volley:

We’ve seen Fritz’s net allergy hurt him in other matches; Djokovic dropped back on key points in their US Open quarterfinal last year, and Sinner used it in key games during their 2024 US Open Final. An excerpt:

On the other hand, this was also an effective tactic [dropping back on return] because Fritz is somewhat allergic, or at least net-intolerant, and doesn’t have the toolset to do what an Alcaraz, or Nadal, or Djokovic, might do when a player drops back like that: serve and volley.

And it’s these kinds of holes — the ones that linger despite being on tour for a decade — that keep players of Fritz’s calibre (that is to say, the man is extremely good at tennis) from ascending to the very top of the sport. Meanwhile, Sinner and Alcaraz swap out techniques and tactics like they’re Jibbitz.

Anyway, this was a great match in its own right — great serving, physical, close — but as these guys are top 10, the standard is measured against Sincaraz (and Djokovic, still, which is crazy). And despite their similar pedigrees, they are almost missing the opposite pieces. There is a technical and tactical core to Fritz that outweighs Shelton. Compare their rankings on Tennis Viz’s metrics:

Forehand? Fritz is ranked 14th vs Shelton’s 56th

Backhand? 15 vs 62

Return? 10 vs 26

Serve? 5 vs 7

Steal score? 116 vs 111

In attack? 16 vs 21

conversion? 30 vs 79

Fritz dominates in nearly every category, and yet, Shelton carves out just as much success it seems. This is where someone like Louis Cayer would make a distinction between “the player” (technique and tactic) and “the performer” (physical and mental), and it’s as a performer where Shelton shines.

In some sense the statistics can never really quite capture the performer; the “swagger”, the x-factored ability to inject pace, the flick of the wrist, and that deep-seated belief that enable them to win points unaccounted on the spreadsheet. I mean, Shelton hit one inside out backhand this whole match. Here:

Interesting to look at the ATP’s “under pressure” leaderboard (which is still just a crude mix of break points/breakers/deciding sets) where Shelton is in the only place that makes sense, given his TennisViz shot ratings but top-10 ranking:

Is it easier to turn a performer into a better player, or a player into a better performer? Fritz and Shelton provide an ongoing case study.

I’ll see you in the comments. HC.