Jannik Sinner defeated Felix Auger Aliassime 6/4 7/6 in the final of the Paris Masters on Sunday to clinch his fifth title of the season. The win takes Sinner back to world number 1 momentarily, and gives the Italian a 3-2 H2H lead over FAA.

Sinner has been on a tear since his US Open Final defeat, registering titles in Beijing, Vienna, and now Paris. He began this final in the same vein, immediately putting the lethal FAA serve to the test in the opening game:

Sinner broke, and sent a further message of his intentions with his own service game; the first four serves were all directed at the Canadian’s backhand, and for good reason. While the serves and forehand of this pair are in a similar weight class, their backhands are not, which meant the backhand exchange had a large effect on this match.

Sinner owns the biggest two-hander on tour, and the highest rated by Tennis Insights. In 2024 the pair had similar spin ratings (~2200 rpm), but Sinner averaged 5 km/h faster, and made 5% more backhands in play. An excerpt from the Dubai Final:

On the other side of the net, the FAA backhand problems are also technical in nature. We can see that the Canadian has a high power position (good for building speed), but also an extreme drop — a feature found in Nadal, Sinner, and Rune. However — and this is critical for a steep drop backhand — unlike Rune, Sinner, and Nadal, FAA’s racquet always stays on the hitting side; he never gets the racquet head far enough back, or the hands close enough to his pockets (more inside), to enable an in-to-out swing path or create a decent stretch-reflex in the right upper back and shoulder. This makes the racquet change paths more abruptly close to contact, reducing his ability to time the ball well. The lack of forward speed from a steep position is what forces the hips to overturn, to “help” the racquet arrive on time, and that’s why he is very front on at contact, again forcing him to roll his hands over the ball, further impacting timing. They are compensatory movements based on a “local” technical maxima.

The changes Sinner has made from juniors to now are stark:

The steep drop and lift of FAA from another angle:

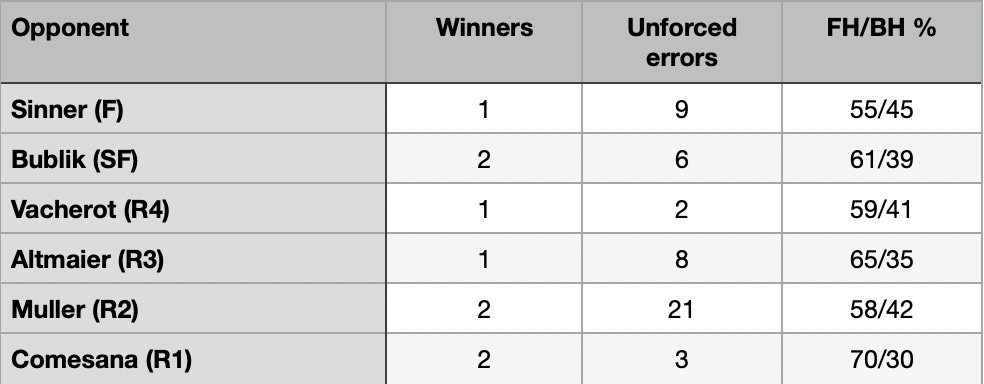

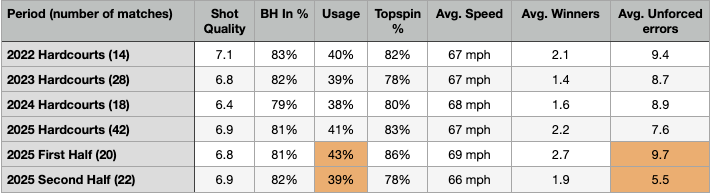

Technical issues aside, it must be said that the Canadian’s season has caught fire in the back end of the season. Courtesy of Tennis Viz and Tennis Data Innovations, I compared some numbers and found some interesting trends on FAA’s backhand. The first is that FAA’s recent run of hardcourt form — all matches post-Wimbledon, excluding his semifinal US Open effort — has coincided with some of the tidiest backhand numbers he has ever posted with respect to unforced errors.

But that’s not all. On top of cutting down on the errors, FAA’s backhand shot direction post-Wimbledon has been starkly different.

In the first half of the hardcourt season FAA was hitting more balls cross court and middle, and only 18% down the line (it got as low as 14% in his Montpellier title run).

However, since Wimbledon, the Canadian has taken his backhand down the line more often, hitting the tour average 24%:

To summarise, in recent months FAA is hitting the backhand less often, changing down the line more often, and making fewer unforced errors. All those things are great for the FAA game. Being able to go line gets Felix out of his weaker backhand crosscourt pattern, and opens up forehand patterns that allow him to dominate opponents. Doing all that while missing less is the dream.

You can bet Sinner knew all this.

The opening point of Sinner’s 2-1 service game was 25 shots of Sinner giving FAA’s backhand some deep tissue work:

In that whole game — which Sinner held to love — Sinner again aimed to serve every first-serve to the backhand; it almost guarantees a decent +1 ball for Sinner. FAA ended up hitting 14 total backhands and only five forehands in that game, with several forehands on the run like above.

And it wasn’t just location. Sinner was bringing some serious heat in the opening eight games:

It’s hard to change direction down the line, harder still if you have a technical glitch, and harder still again when you’re consistently faced with 130km/h incoming rockets.

As a result, the recent trends in FAA’s backhand game fell away.

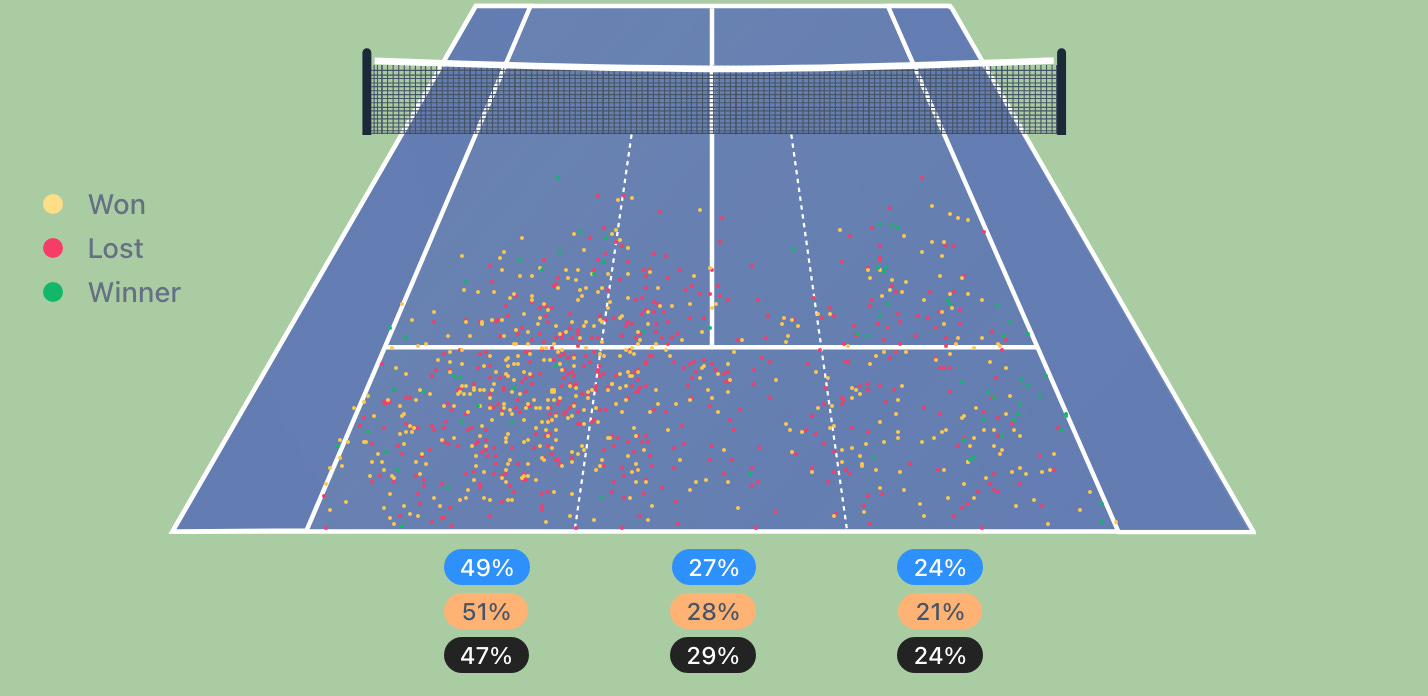

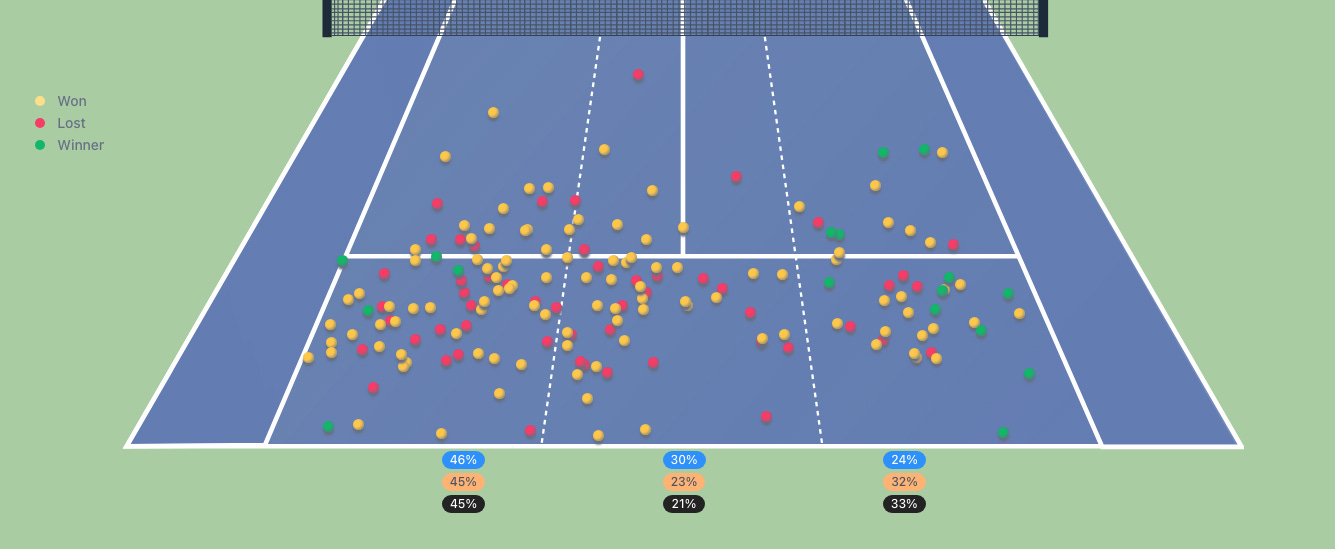

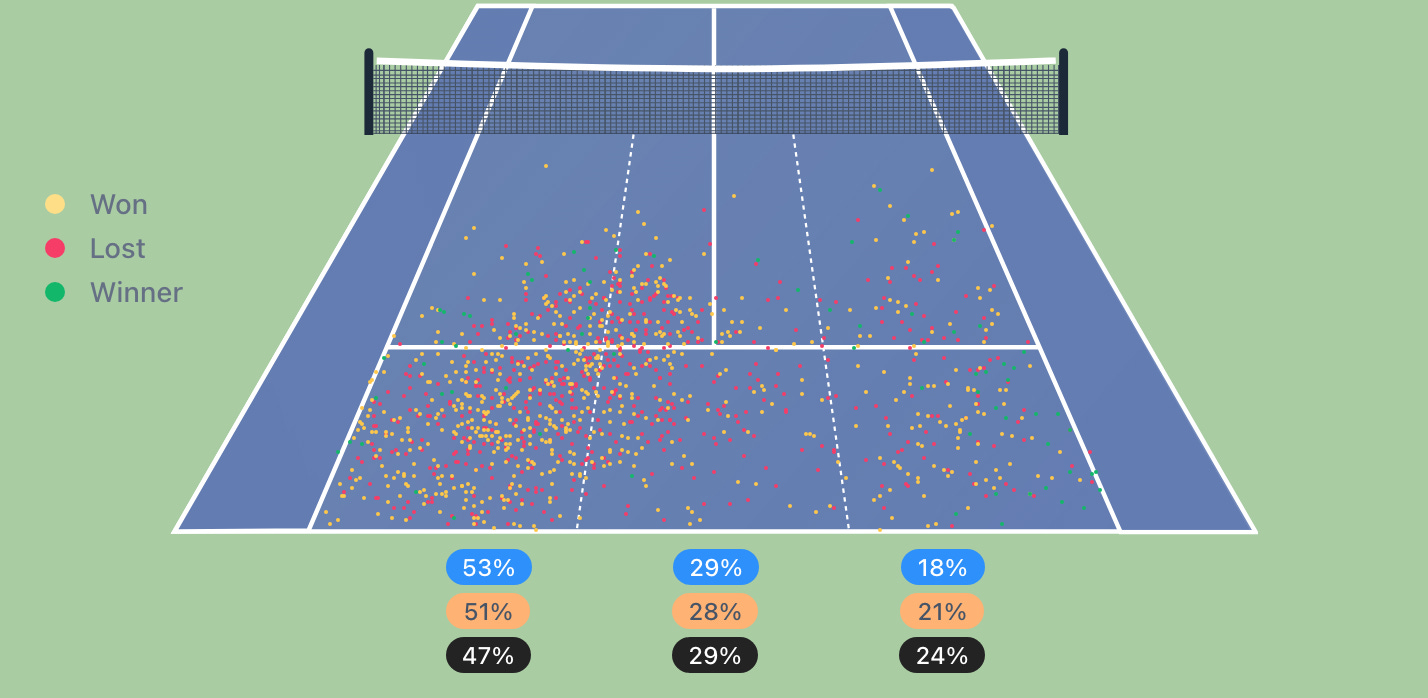

His backhand down the line percentage for the match would finish at a very low 13%, while his backhand usage would be a very high 45% . It was the sternest examination of that wing all week, where FAA was able to find his tour average (58% forehands) or better in every other encounter:

A look at Sinner’s rally chart off both wings showcases how selective he was when going to the FAA forehand; the ball was nearly always on his terms when going there, and out of the 43 shots played into the FAA forehand wing, 12 were Sinner winners.

Backhand differences aside, FAA and Sinner are two of the deadliest serve +1 guys on tour — especially indoors. I thought both were pretty exceptional tonight, but Sinner just straight up stole a couple of points he had no business winning. For all the firepower you must contend with against Sinner, even when attacked the Italian is a nightmare:

There was a period midway through the second set where FAA looked like he might get a look into the match. His intensity and overall quality of game was staying high, waiting for any kind of opening the Italian might offer. He got to 30-30 on Sinner’s serve at 2-3, courtesy of a line forehand heater and a Sinner double fault, and even the crowd kind of sensed this was a moment, and Jannik played a perfect forehand drop shot — one of only three in the match — to quickly snuff out any hope.

The very next game the Canadian was forced to save three break points, which he did courtesy of more big serving and plus one-forehands, and was doing good on making the most of any attacking opportunity he was presented with:

We got to a tie-breaker, and in a way it cracked open the protection that regular games afford players when playing against Sinner. Throughout the match Sinner had reached 30 in 8/11 FAA service games, generating break points in three different games; he was always applying pressure. By contrast, FAA had got to 30 in only 3/11 Sinner service games, and didn’t generate a break point all match. This tie-breaker was more of the measured backhand-targeting play from Sinner, and FAA really only blew one point: the +1 forehand at 2-2:

“When a match is being played with such fine margins, that can be costly.”

— Tennis TV

But those margins were only applicable from one end of the court. All match long, Sinner was able to play in a kind of holding pattern through the FAA backhand, until he opted to attack, and often he got opportunities — like on the very next point — off of his second serves:

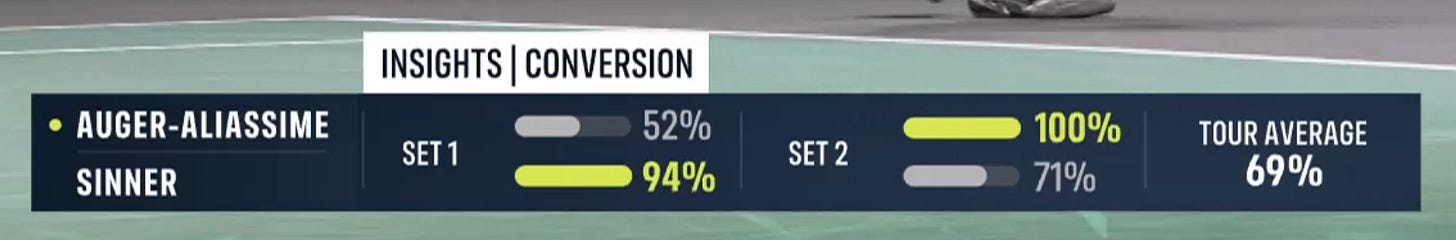

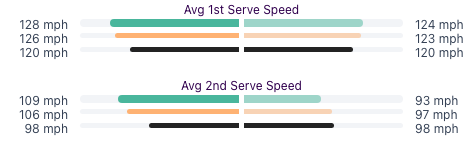

FAA’s second serve was huge in this match. He averaged 109 mph — 16 mph faster than Sinner’s:

But the return speeds were comparable, and the spin rates tell you that FAA’s backhand return wasn’t penetrating enough, but sitting up with spin. I’m guessing it was by design that Sinner took speed off his second serve in this match in order to get an even slower ball back from FAA, given the swing issues already discussed.

He wrapped up the title with a familiar pattern: backhand exchanges, pulling the trigger into the FAA forehand corner on his terms:

“It’s huge, honestly. It was such an intense final here and we both knew what’s on the line…From my side I’m extremely happy. The past couple of months has been amazing. We tried to work on things, trying to improve as a player, and seeing this kind of result makes me incredibly happy.”

— Jannik Sinner

That’s all I got.

I’ll see you in the comments. HC.