Five years, seven prototypes, and one wildly ambitious idea. Join the small team at Telepathy Bikes in Bozeman, Montana, as they add the finishing touches to their production steel full suspension built around the world’s first Parallel Axle Path linkage. As Matt Lessmeier recalls, Telepathy didn’t begin as a company; it began as a daydream shared by a handful of overconfident engineering students who believed they could build something better. Follow their messy, humbling, exhilarating journey below…

As I write this, we are adding the final touches to the first Telepathy bike to hit the market. Preorders will be live starting in the winter and our bike can be in customers’ hands by the spring of 2026. This is the first bike to have the Parallel Axle Path, and it is a culmination of years of testing, dreaming, and fabricating. Telepathy started as an idea, maybe even a daydream. The jump between conception and realization feels meteoric, but in reality the process has taken 5 years, 7 iterations, a career shift, and a whole lot of learning. This messy, humbling, and beautiful process is the foundation of how and why Telepathy exists, and I’d like to share it with you.

A Round Table Meeting

I wish I could tell you how it was all one grand scheme from the beginning, but that’s not how it went down. Telepathy began in 2020 when an overly ambitious gentleman named Calvin decided to start a bike company. He sent a mysterious email to all the mechanical engineering students at Montana State University asking for help. A handful of college students responded.

I remember going around the table at that first team meeting and saying why we were there, as a sort of icebreaker. There were five of us in total – Calvin Servheen (an industrial engineering student), Kari Perry, Andrew Aron, Ava Paul, and myself, all enrolled in the Mechanical Engineering program. Most people said things like “I want to be a part of something cool,” or “I want to learn about bike design,” with restrained enthusiasm. In my mind, there was only one reason why we were all sitting around a conference table in some obscure corner of the MSU campus, and it wasn’t just to be a part of something cool.

If we had wanted to be a part of something cool, we would have applied at a big bike company or joined intramural volleyball. If we were forming our own organization, it could only be for one reason: we wanted to do better. We were going to build better bikes than anybody had ever built before. Why else would we need our own organization, our own company?

It was one of those rare moments of overconfidence; the type of decision that we would’ve never made if we had known how hard it was going to be. A string of these moments led us to where we are now.

The Idea

We wanted to build a better bike, but where to start? Bike design, it seems, is a game of varying the balance between fun and stability by changing the travel or the wheelbase. Like a balance beam, it appears impossible to raise both sides at once without breaking the paradigm. The more travel you give the bike, the more stable, the less fun. Every changeable aspect of the bike that we could think of was the same – it boiled down to a tradeoff between the same two attributes.

We had to go back to basics. Forget about the Horst Link for a minute; what is the problem with current mountain bikes? It ain’t straight line stability, I’ll tell you that. It’s cornering. Everybody wanted to figure out how to quit washing out the front wheel. It was also my personal pet peeve. I loved hitting a corner, doing it again and again. I obsessed over shralp marks and the body position that affected them.

Several nights later, it hit me: the cornering radius. I had been thinking about why some bikes were sluggish and my engineering brain reduced sluggish to cornering poorly, cornering poorly to something being wrong with the cornering radius, and cornering radius to wheelbase. There it was, it was obvious. The best bike is one with a rearward axle path that is parallel to the front. That way the wheelbase would remain constant as the bike g’ed out into turns. Constant wheelbase, constant cornering radius, more control, more fun. There it was: the parallel axle path could be more fun, and it could also be more stable.

The idea made sense to me, but I did have my moments of doubt. After all, this was so different from what everybody else was doing. I thought about the parallel axle path all the time, trying to poke holes in the physics. There were a lot of little problems, but they were practical, not fundamental. They could be solved.

Eventually, I would come to appreciate that any new idea has a lot of inertia behind it. People are comfortable with the status quo and hesitant to make big changes. But big changes are needed for big improvement. As David Rowland said, “Better is always different, but different is not always better.”

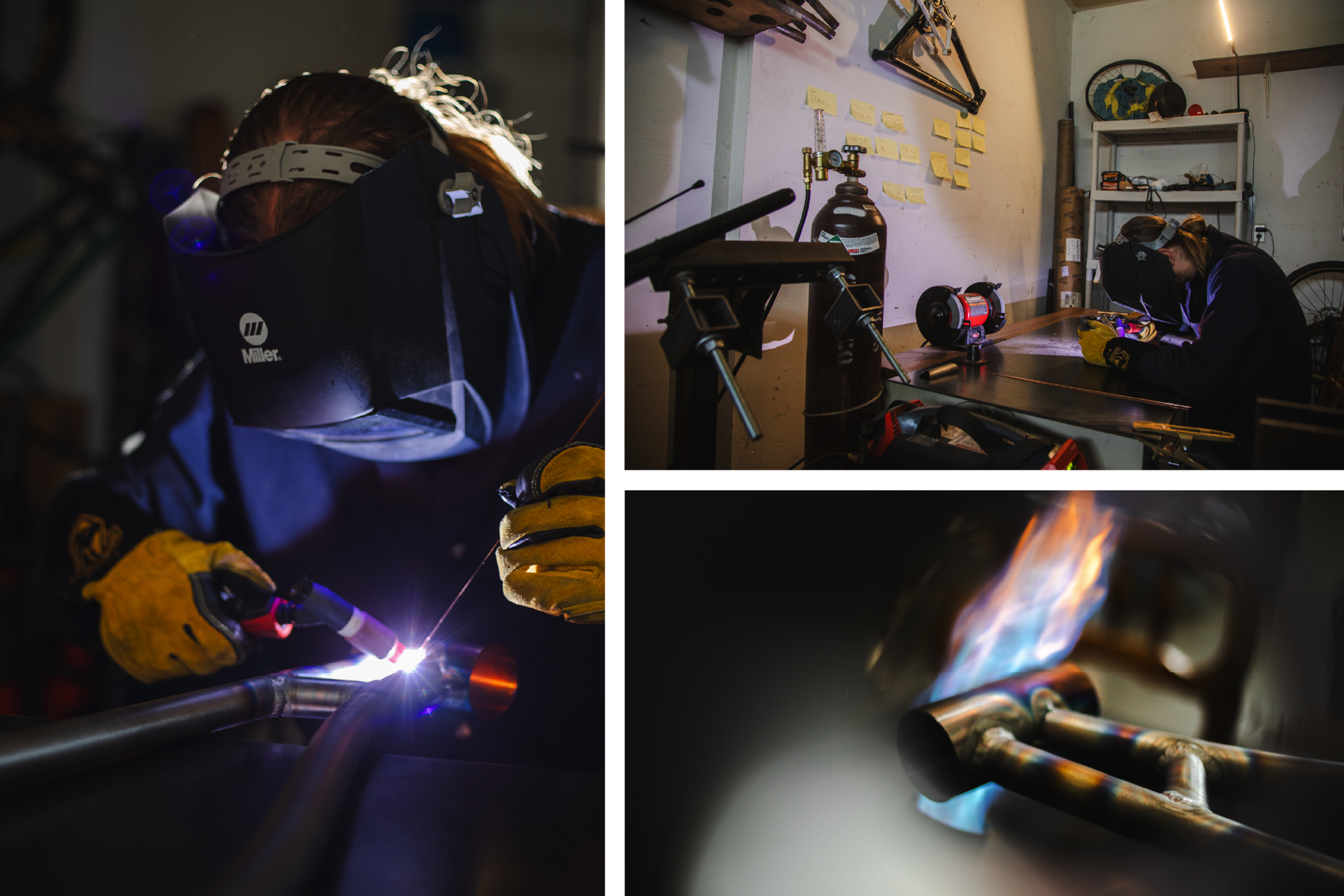

Zac Nelson (left), Matt Lessmeier (top right), and Zac welding the first front triangle (bottom right)

Steam Engine or Bike?

With the axle path decided, the task was finding a linkage that could produce it. Initially, we liked the simplicity of a single pivot, but single pivots have a problem. The wheel path is always a portion of a circle – it’s curved, it can’t be straight.

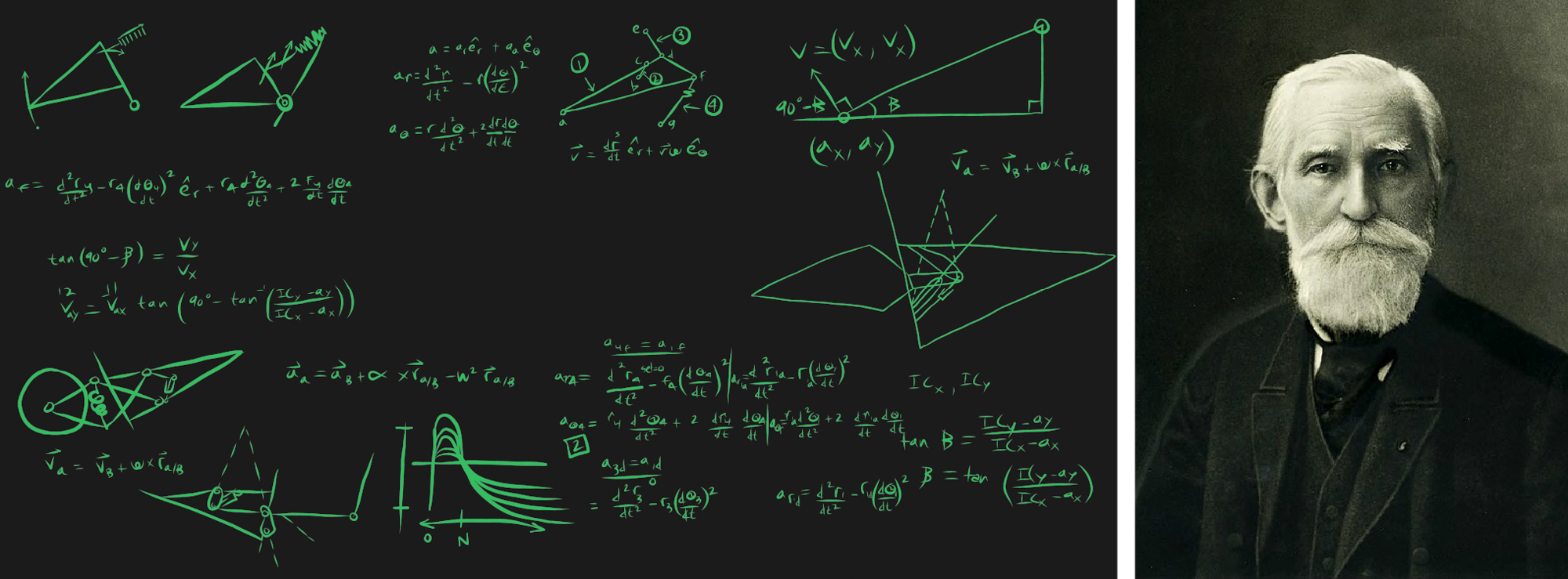

Then I realized this was not a new problem; it was the same as that encountered in steam engine locomotion in the 19th century.

Chebyshev was one of the great 19th-century mathematicians, and his linkage took the linear motion at the piston cylinder of the engine and turned it into rotation at a train wheel. I decided to do the opposite – I took the rotation at the shock and turned it into linear motion at the rear wheel, tilted back at an angle of 64 degrees to the horizontal. That was how I created the Sync Link.

Then, how to build it? As broke college students, we naturally wanted to see if we could use MSU’s vast resources. We organized some meetings and ended up in the garage of Craig Shankwitz, capstone professor, answering a barrage of questions that did more than hint at his skepticism. This was not hollow skepticism, either – Craig knew what it would take from his years of motorcycle tinkering. Thankfully for our dreams, Craig is a risk-taker, and he eventually allowed us to sponsor a capstone project.

The opportunity came with an ultimatum: succeed, and we open the door for future student-sponsored projects; fail, and we close the door forever. We only had one shot, and I was determined to make it count.

The beginnings of a new linkage design (left) and Paufnuty Chebyshev, the inventor of the 19th-century linkage that inspired the Sync Link (right)

Business Advice

Luckily, we got some funding from local business competitions and a grant to help with the expenses. Starting a company is expensive, and I am grateful to Blackstone Launchpad, MSU, and the local Bozeman community that supported us without any strings attached.

I hope to show you that starting a company is possible, so that some of you may be inspired to start your own. Capitalism works best when there are lots of new companies creating value. Without them, it is just entrenched corporations taking advantage of markets they control. While this may increase efficiency, it doesn’t necessarily create value for the average Joe. Only innovation can create value, and history has shown us that new players do innovation best.

For me, starting Telepathy was the beginning of a dream come true. Actually, I hadn’t even dreamed this big. I hadn’t thought it possible. I thought I might be working for another bike company when I decided to pursue engineering. Well, let me tell you, working for yourself can be much more fun and effective. Setting your own schedule is definitely a positive, but usually it means that I end up working all the time.

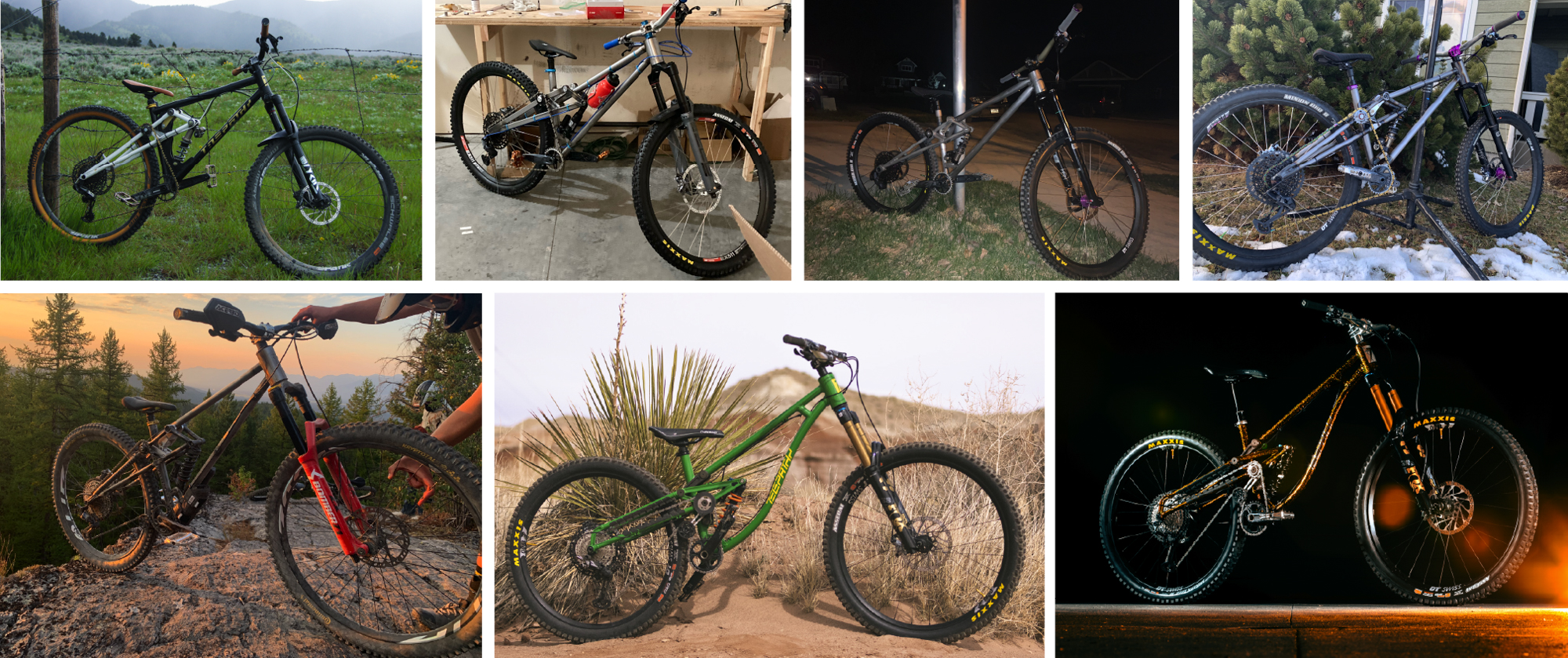

The first Telepathy prototype, made as a capstone project at Montana State University in the winter of 2021-2022. Photos by Helen Bruil.

Prototypes

We managed to put that first bike together, despite the frame assembly taking all night due to the use of (way too many) washers as spacers. We had an excellent capstone team that was willing to work hard, much harder than the average project. Zac Nelson did an excellent job welding it. Andrew Aron designed and built the jig, and Jake Sieb did the machining.

I am grateful to those guys for bringing the dream to life. They helped me to stop overthinking and just build it. You never know until you know. That was a major theme in the development process later on. Don’t fix what ain’t broke, but to find what’s broke, you first have to break it.

We also learned a whole host of practical lessons. Namely, just how good an angle grinder can be at making things fit.

When we went to take it out on that first ride, I was nervous. After all, this was crazy compared to what other people were doing. But luckily the bike was much better than even I had anticipated. It had a magic feel to it in loose, rutted corners. It seemed to generate more traction the harder you pushed into it. This was to be expected, but I hadn’t fully appreciated it before that first ride.

The more you compress the linkage, the more front wheel traction it generates. As the contact patches shift back, they put more weight on the front wheel, giving more traction.

I was convinced, but the bike was heavy, I was hitting my knees on bolts, and it looked, well, it looked like a college project. So the next phase of Telepathy was born with the goal of commercializing what was before only an experiment.

Making the 6th iteration, the first of the second generation Sync Link. Also, the last prototypes that were made in my garage.

Development

We proceeded by making more bikes. Many more bikes. The changes were often small, and the lessons great. We found how flexy was too flexy, how high of an idler was too high, and we made it lighter. It was still heavy, mind you (this is steel), but not in a way that adversely affected the ride quality.

This was a period of evolution for Telepathy. We did sponsor another capstone, and then tried to bring in an outside welder. But ultimately, we needed more control and independence over the build. I learned to weld during my first year of grad school, and after a year of practice I was ready to start welding bikes myself. I outfitted my garage with all of the tools necessary to build bikes: my own TIG welder, coping jig, and lots of hole saws.

The hammer is my favorite tool, and the headlamp – a necessity of working in a dark garage.

From there, it was game on. Before, we had built about 1 bike a year. Now I could build many, taking only months to test, redesign, build, and iterate. This is when I truly came to appreciate the art of building bikes. There is a substantial joy in creating something, especially when you get to ride it afterward.

When we realized that the idler was indeed too high, I redesigned the suspension to accommodate a lower idler and improve the ergonomics. While I was at it, I figured out a way to nearly eliminate chain growth, adding much to the suspension’s sensitivity. Now all the practical problems were solved. This takes us to the current design. All that remains is to create additional sizes, and of course, the real problem: trying to make the thing halfway affordable.

The Build

Sometimes it’s hard to work for a long period of time at once, especially at the computer. But not in the garage, not when building bikes. A kind of trance takes over where all I can imagine is the goal, the finished product. And the steps keep flowing, like the molten metal in a weld pool. I have never been so excited to work 14-hour days in my life.

After bending the downtube, the process starts with coping – cutting circles in the tubes. I do some of this manually, some I have laser-cut (particularly the top tube with the pivot hole). I’m sure my roommates appreciated the laser-cut tubes in those days. The welding is quiet, but the coping is horribly loud.

The next step is fitting the tubes. I have always been amazed at how precise the human hand and eye can be. I have had things CNC’ed to seemingly tight tolerances, only to find they don’t quite fit the same as a hand-shaped piece. Hand fitting may not be as scalable, but it is certainly precise.

Then, the fun part: the welding. While the rest of the process is rough, welding is where the artist comes out. Dragging a weld pool brings on a state of entraining focus that is somewhat beyond the simple utility of the process.

After welding, you have to post-process the frame to clean up holes and make sure everything fits. Then it’s off to the powder coaters and I get a break. It took nearly 2 weeks for me to build these frames, but most of my time was spent fixing unforeseen issues. The actual frame fab and welding was quick, and we got them done just in time for some testing.

Production

We expect to begin our first limited production run this winter. If you are looking for a light bike, or a cheap bike, or a bike that prioritizes pedaling, then you will want to look elsewhere. If you are looking for a bike designed to maximize fun and balance everything else, welcome.

Our bikes are made in Bozeman, MT, by me and a small group of people. The frames are made entirely locally, from the machining to the paint. This makes them more expensive, but if you buy one, your dollars will support our local community. You can walk into the shop and meet the welder, and be assured that you are supporting the local machinists several blocks down the road. This is your chance to get behind innovation and opportunity, and you can look the builders in the eye and watch your bike being made right here in Montana, USA.

In any case, we hope you will be a part of our story going forward, whether that is buying a bike, sharing with your friends, or just following along.

If you are interested in buying a Telepathy, sign up on the waitlist.

“Ideas are like seeds, apparently insignificant when first held in the hand. But once firmly planted, they can grow and flower into almost anything at all, a cornstalk, or a giant redwood, or a flight across the ocean. Whatever a man imagines he can attain, if he doesn’t become too arrogant.”

~ Charles Lindbergh, pilot of the first trans-Atlantic flight

Prototypes 1 to 6 and the show bike, from 2021 until now

Check out more at Telepathy Bikes.