You might have heard that Jannik Sinner did something in 2025 that no one has ever done before. For the first time since modern statkeeping began in 1991, he led the tour in both hold percentage and return percentage. There’s a caveat here, because Sinner missed most of the clay season, which might have dragged down his return numbers relative to the field. Still, it’s a tremendous accomplishment.

Only a few players have ever come close. Novak Djokovic ranked first in hold percentage and third in break percentage in 2023, and Andre Agassi reversed those rankings in 1999. In 1995, Agassi had placed third in both categories. Only a handful of others–basically the Big Three–have ever cracked both top fives simultaneously.

We owe this whole framework to Cracked Racquets majordomo Alex Gruskin. He likes to talk about “clubs” of players who rank in the top 10, or top 25, or whatever, of both hold and break percentage. It’s a great way to quickly identify the best all-around players on tour. “Top 25” may not sound impressive, but this past year, only nine men made the cut. Doing so is a near guarantee of a top-ten finish. Only Casper Ruud (year-end #12) and Grigor Dimitrov (injured since Wimbledon) were top-25-clubbers without also finishing top ten in the rankings.

Sinner, then, is on another planet, and most players are lucky to sniff the top ten in one category, let alone both. That said, the number of all-around superstars is creeping upwards.

Three guys–Sinner, Djokovic, and Carlos Alcaraz–qualified for the top ten club this year. Jack Draper just missed, finishing 11th in break percentage. Excluding the 2020 Covid season, this is only the fifth time since 1991 that three men qualified. All but of those seasons have come since 2019. The most common number of top-ten-clubbers in a single year is one. There times in the 1990s, there were zero.

The story is similar regardless of the threshold. 2023 saw nine top-20 clubbers, the most ever. For the first fifteen years of ATP statkeeping, the average season delivered fewer top-25 finishers than that.

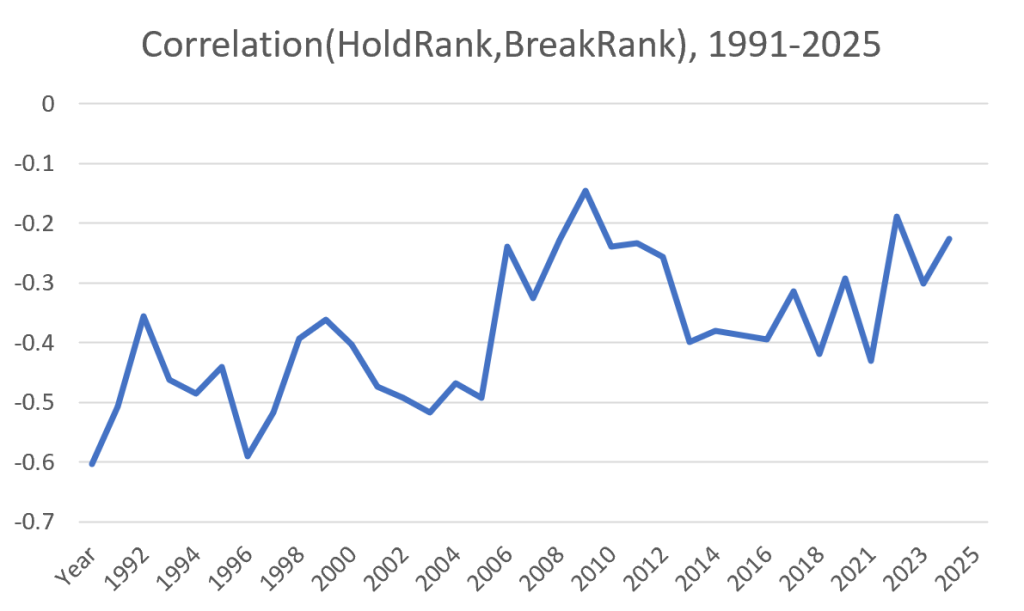

The trend is clearest when we boil it down to one number. For every season since 1991, I took the top 50 from the year-end rankings and worked out their positions on the hold and break percentage lists. This graph shows the correlation between hold ranking and break ranking for each campaign:

A correlation of zero would mean that there was no relationship between a player’s hold and break ranks; negative means that if someone is high in one category, they are more likely to be low in the other. Of course, it’s a matter of degree. Over time, the inverse relationship between serving and returning skill has eroded. We hit peak well-roundedness around 2010, and we appear to be back in a similar state of affairs.

Why?

This is where it gets interesting. (And, I’ll admit, rather speculative.)

In sports (and the economy in general), specialization tends to increase over time. We rarely see multi-sport athletes these days. NFL players once played both offense and defense; now specialists handle each side of the ball. Baseball teams once got through entire seasons with a handful of pitchers; now it can take as many arms to get through a single game. Specific skillsets are deployed to handle right-handers, left-handers, and the late innings.

This has happened in tennis, too, kind of. There has probably never been a better server than John Isner. Never a stronger returner than Novak Djokovic. Setting aside skills that have fallen into the background in today’s game (everything associated with net play), the best of every specific thing is on display now, or has been recently. This isn’t to say that Richard Gonzalez, or Ken Rosewall, or Ivan Lendl couldn’t have done it better. They just didn’t have the chance. Modern sports encourage early specialization. The whole ecosystem then delivers training, coaching, and equipment that yesterday’s greats never dreamed of.

But! Isner only (“only”) peaked at #8. Diego Schwartzman, who at his best rivaled Djokovic as the sport’s most brilliant returner, also topped out at #8. We all know why: Neither one was very good at the other half of the game, at least by pro standards. In the NFL, half of a player’s job was handed to someone else who was better at it. At the Olympics, the entries in the 400 meters and the 800 meters can be given to different athletes. In tennis, though, Isner’s gotta hit the returns, and Peque had to serve.

Player development, then, becomes a sort of optimization problem. Do you find the most extreme physical specimens you can, then coach them to adequacy in the skills that don’t come naturally? Or do you look for all-around talents, even if they’ll never hit a 140-mile-per-hour serve?

The answer isn’t obvious. But the trend is moving toward the latter. I think I can explain why.

In short, we’ve reached peak server. You could find players with the potential to develop bigger weapons than those of Sinner, Draper, Ben Shelton, Alexander Bublik, and the like. But they’re already holding 85% of the time. Even Ruud and Alex de Minaur, with their limited first-strike capabilities, are able to hold nearly that often. At the risk of a misleading pun, we’ve reached diminishing marginal returns. A better server might eke out another percentage point or two, but at what cost? A whole lot of guys would love to have Shelton’s serve, but would they take the Shelton return along with it?

Specialization is in decline because the floor keeps rising. A few generations ago, a one-dimensional savant with a monster serve or a wizardly backhand could rocket into the top 20 because not enough opponents could stop them. Now, Reilly Opelka might hit 30 aces, or he might get broken three times by #92 in the world. There are probably guys out there who could serve even bigger than Opelka or Bublik, or maybe even return better than de Minaur. But if they can’t meet a (steadily increasing) minimum level of competence on the other side of the ball, they’re marooned on the ITF tour, at best.

This, too, has parallels in other sports. Really, any sport where coaches are stuck with the same athletes on offense and defense. In the NBA, versatility is prized like never before. In baseball, teams are less likely to carry a slugger who is a liability in the field. There are just too many other options: Why use a limited player when an almost-as-good hitter could give you considerably better defense?

Think about it: In the ATP top 50, are there any bad servers? A few South Americans, plus Corentin Moutet. Learner Tien has some development yet to come, and that’s about it. Bad returners? Sure, a few, but any as weak as Isner was? (Or, heaven forbid, as Ivo Karlovic?) When Opelka was coming up through the ranks, everyone raved about how his backhand was in another class than Isner’s. Shelton’s game is incomplete, but he has a lot of skills on the ground. No one would call him hopeless out there. All of his natural talent and hard work translated to 47th out of the top 50 this year in break percentage.

Some of this is thanks to equipment. Modern rackets and strings make it possible to return more first serves, with control. Those thread-the-needle passing shots that everyone can hit these days? A couple of generations ago, they were little more than swing-and-pray low-percentage lunges. Technical advances benefit everybody, but they probably do more to shrink the gap between the haves and the almost-haves than they do to increase it.

Beyond that, we’re watching the natural outcome of an individual sport with an ever-expanding talent pool. Hyper-specialization won’t get you to the top, so well-roundedness is the only option. With millions of kids growing up watching Carlos Alcaraz, the bar will continue to rise on both sides of the ball.