Buy The Art of Batting here:

Kagiso Rabada won this game. Fazalhaq Farooqi could have. Rahmanullah Gurbaz almost does, twice. Lungi Ngidi also feels he closes it off on a couple of occasions. Quinton de Kock and Ryan Rickelton probably think they have it buried. Rashid Khan has two chances. Azmatullah Omarzai must believe he wins it. And Keshav Maharaj certainly has a big moment too.

But the 13th Match, Group D, Ahmedabad, February 11, 2026, ICC Men’s T20 World Cup is like a zombie. It keeps coming back from the dead. South Africa cannot bat Afghanistan out of the game. The Afghans cannot keep enough wickets in hand. But then, Kagiso Rabada takes the final wicket to finish the match, winning it by 12 runs. The players start to celebrate and commiserate when the no-ball siren sounds. A nightmare for any bowler, but Rabada has just won the match, and now he hasn’t.

He is a heel, because his heel was over the line.

Little did any of us know that this was just the beginning of the game that wouldn’t die.

***

In this match, Rahmanullah Gurbaz was dismissed twice by the same bowler. That is not a thing that usually happens in a T20 game.

But this was weird before the end. South Africa cannot get started at all – they are 12/1 after three overs. In the following nine, they add 112. de Kock and Rickelton feel like it is about to break the game open. Especially as it is the Afghan spinners taking punishment.

All except Rashid Khan.

In one over, he takes two wickets, both the set men. It turns out they are the only two players who score at pace. South Africa then limp forward until the final two overs, when they find boundaries to reach 187. It is a patchwork quilt total; it has a little bit of everything. At various times, the projected scores are 151 and 207. They make 187.

Noor Ahmad gets belted, and so do all the seamers late on. Rashid is the only bowler who looks in control – even one of his boundaries comes via a fielder running past the ball.

But Afghanistan make the chase look easy. They are 51 after 4.1 overs. South Africa look stuffed.

Then three wickets fall in seven balls. Two brilliant deliveries from Ngidi, and a very lucky one from Rabada. Afghanistan rely on their top order, and most of them are gone.

But it feels like two matches are being played – one where George Linde gets smashed by Gurbaz, and the other where South Africa are on top. Gurbaz is so good he pushes Afghanistan ahead.

South Africa’s main weapon is Keshav Maharaj’s frugal nature. But Gurbaz scores his seventh six of the game against the spinner, and Afghanistan need 67 from 46 on a good batting pitch, with seven wickets in hand.

Next ball: Gurbaz is out.

That wicket puts South Africa back in charge when de Kock completes a sharp run-out in the same over.

It is scrappy from here. South Africa don’t quite finish it, but Afghanistan cannot regain control either. Boundaries and wickets follow each other. When Ngidi removes Omarzai in the 18th, Afghanistan need 24 runs from 12 balls with Rashid and Mujeeb Ur Rahman batting.

When Rashid is caught on the rope by David Miller, finally the game feels done. Noor Ahmad – with a T20 batting average of six and a strike rate of 98 – walks in.

The number ten’s first ball from Marco Jansen travels almost 100 metres. It is his 14th six in 195 matches. But a dot follows, and Noor looks unsure. The final ball of the over he hits straight back to Jansen and runs; Mujeeb has no chance.

So now it is 13 from six with only one wicket in hand. That six from Noor feels like a final breath of a death rattle.

The legend Rabada returns to finish the game. It does not matter that it is a full toss down leg side – it is somehow sliced to cover by Noor, and that is that.

Pack it up. Game over, man. Game over.

That is when the siren goes off.

From here, we enter an entirely different universe, where cricket norms are stamped on, logic plays no part, and even the least likely outcome seems ready to happen every ball. It feels like the entire cricket universe is glitching.

One of the best bowlers in the world follows his no-ball with a wide. The free hit stays alive. The next ball is struck straight to long-off, where Jansen stands – and he fumbles it. But they don’t take the run, wasting the freebie. Surely it is done now.

But Noor pulls a short ball from Rabada for six. His 15th in 195 T20 matches. He is suddenly Lance Klusener. In more ways than one.

With five needed from four, Noor starts to overthink. Always dangerous for a bowler. He hits out to a sweeper, runs halfway down the pitch and decides against the single.

Now it is five from three, and a messy swipe drops into midwicket pocket, bringing two. But Rabada, who has 588 international wickets at 24.39, has overstepped once more. They now need only two from three. South Africa want one wicket.

Afghanistan coach Jonathan Trott tries to send a message, but the umpires send the 12th straight back.

Rabada bowls a full, wide delivery on the free hit, and Noor drives it between cover and long-off. Jansen races around, gathers cleanly, and throws back as Fazalhaq Farooqi charges for the winning two. The throw is wide. Rabada collects and dives at the stumps.

Something has happened, but no one is sure what. But live, it looks like Afghanistan have won this match. Rabada tried hard to make up for his error, but finally the game is over, and Afghanistan win.

Until we see the first replay. Then it is close, very close, but Rabada has done it; he has saved the game he won earlier and given his side one more life in it.

Farooqi is a centimetre short = Super Over.

Ngidi bowls to Omarzai. He starts with a wide delivery slashed away for four. The next ball is hammered straight – it should be caught – but even the towering Jansen can’t reach it. Ten runs from two balls. South Africa fight back. Gurbaz looks exhausted in the Super Over as well. Rabada gets another moment of redemption. He dives at deep point, spills one, but fumbles it on the right side of the rope. It is his entire day, a mistake and a save in the same breath.

Afghanistan set a decent 17 runs.

Trott speaks to Rashid Khan. The question is obvious: should Rashid bowl? He looks desperate for it. He has been outstanding.

But Fazalhaq Farooqi takes the ball.

Brevis launches one deep into the stands from a fast short ball. Then he falls to a slower short ball. Stubbs edges a perfect yorker for four. Another yorker produces a dot. Seven are needed from one ball. Again, this is over. We can do maths, we understand what this means.

The only chance, the miracle South Africa need, is clearly too much – the six off the last ball.

Especially when Farooqi goes full again, this is his chance to end the game. He couldn’t run fast enough before; now he just needs to not be hit over the ropes. He goes for the yorker, but gets the low full toss. The kind of ball it is impossible to get a helpful launch angle on.

But Stubbs brings out the set square and finds the perfect trajectory to match power with placement a few feet over long off’s head.

The game was dead again, and the game is tied again.

Second Super Over.

Now Afghanistan will bowl Rashid Khan. Their champion, the in-form bowler in this match. It is a no-brainer.

And it is a no; Omarzai bowls. A fifth bowler and allrounder.

Stubbs hits his second six in succession. A single and two follow. Then Miller launches a slot ball about 33 rows back. The next delivery is a full toss – almost a no-ball – and it disappears into the same stand. Omarzai looks broken, but he finishes with a fine yorker, conceding only a single. But this over feels like chaos.

When Stubbs and Miller run confidently from the ground (with Afghanistan looking tired and sluggish), the score on the screen says they made 17 in that over. But that is because in all the chaos, the TV feed lost a six.

South Africa actually make 23. No one involved knows what the hell is happening.

In a traditional narrative, Rabada just comes back on, wins the game, and we all forget about his heel turn from earlier in the day. Surely this is his time. But instead of their great bowler, South Africa choose Keshav Maharaj.

In a match with four super overs, somehow South Africa don’t use Rabada and Afghanistan snub Rashid Khan.

Mohammad Nabi walks out to bat and looks every one of his many years. He swings at a friendly ball in the slot and misses. He and his team look tired, and when he guides the second ball to point, finally the game is over.

The math is still mathing, but really, no one is expecting 24 runs in four balls.

For a while, these teams were locked in an endless spiral. But now, Afghanistan look tired, South Africa are full of energy. Maharaj will finish his over, because you have to bowl out in cricket, but they are one ball away from where they could stop and shake hands.

To finish this charade, Rahmanullah Gurbaz comes in. Before he faces his first ball, something strange happens – Maharaj and the umpire seem to whisper to each other, they’re leaning in and getting cozy. It is like the moment in a zombie movie where the leads share a laugh, because they know they are finally safe.

But Afghanistan RISE.

24 from four becomes 18 from three as Maharaj tries a quicker length ball and is struck hard into the stands. No, this can’t mean anything. Then next ball he takes pace off wide to stretch Gurbaz, but it flies towards long-on. It goes to Jansen – it feels like a catch – until it doesn’t.

Wait, is this happening?

Finally Maharaj gets it right, and aims for the leg-stump yorker. But he misses his length slightly, and it is launched into the crowd again.

Wide. Short. Fast. Slow. Straight. Yorker.

Maharaj tries everything, Gurbaz hit sixes.

IT’S ALIVE.

Gurbaz needs one more maximum when Maharaj lands the wide yorker correctly, except it drifts a few centimetres beyond the wide line.

Gurbaz leaves it. The guts to do that then. Maybe this match should finish with a wrong call on a leave.

But instead we have new maths, with one ball remaining, a four ties it, a six wins it.

The internal logic of this match suggests that it will be a four, ‘one more tie is it, lads’. But it feels like Gurbaz, even with that pause for the wide, is going to hit another six.

Gurbaz has launched Maharaj over the rope four times already, and hit more than ten sixes in the day.

But the South African spinner also got him out. An hour or so back, he’d bowled a full wide one after being hit for six, and Gurbaz sliced to a fielder behind point.

Here they are again, two tired warriors, who feel destined to fight to the death.

Neither the opener or the left-arm finger spinner should be involved with the final ball. But fate kept bringing them together.

Maharaj bowls wide again. It’s not a sexy ball; it is the one he was searching for, and the one that worked for him earlier today. Gurbaz slices it, and the exact same thing happens again, another catch behind point.

In a game of power and nonsense, it is won by a consistent, slow left-arm orthodox ball. Not a moment of chaos, but a repeat of action from earlier in the day. Not the speed of Rabada, the mystery of Rashid or the power of Gurbaz. Just Keshav Maharaj with his foot behind the line stops Gurbaz winning it, twice.

Keshav Maharaj’s real game return is 4 overs, 1/27. His Super Over: 2/19.

A lot of people before him tried and failed. But Keshav Maharaj finally kills the game that would not die.

***

Rahmanullah Gurbaz’s all-time great knock

Rahmanullah Gurbaz was the highest run-getter in the 2024 T20 World Cup, though a 55-ball 43 versus Bangladesh – where they managed to defend 115 – heavily dragged down his strike rate, By the end, it was 124.3. He had played three huge knocks: against Uganda and New Zealand in the group stage, and Australia in the Super 8s. But all of those were batting first. In chases, he just couldn’t get going.

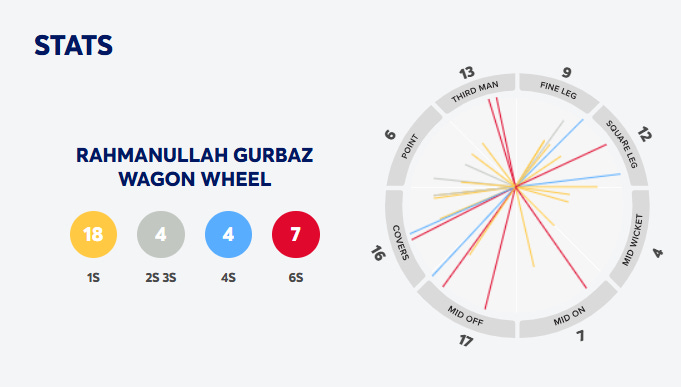

Today, he played one of the most audacious knocks you’ll ever see. He was backing away and playing some sumptuous shots to both pace and spin. There were only nine dots, and five of his seven sixes were actually on the offside.

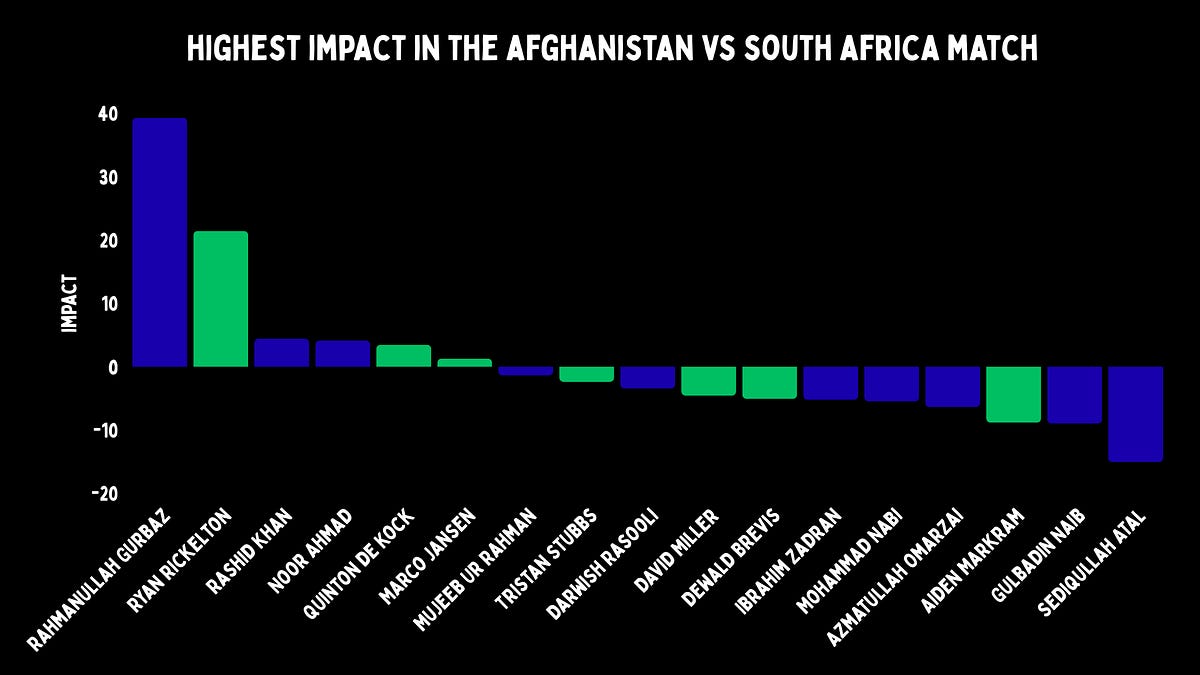

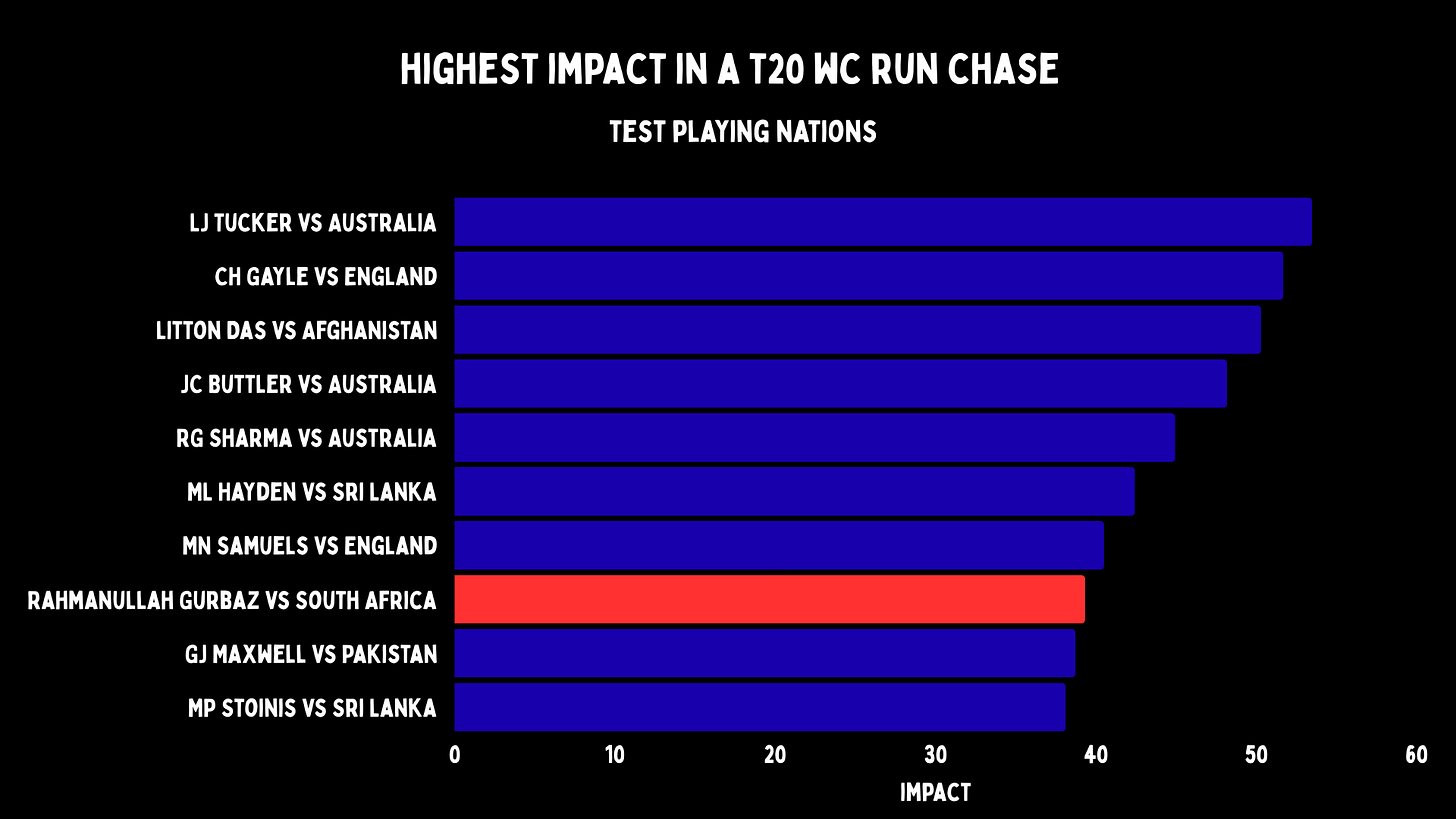

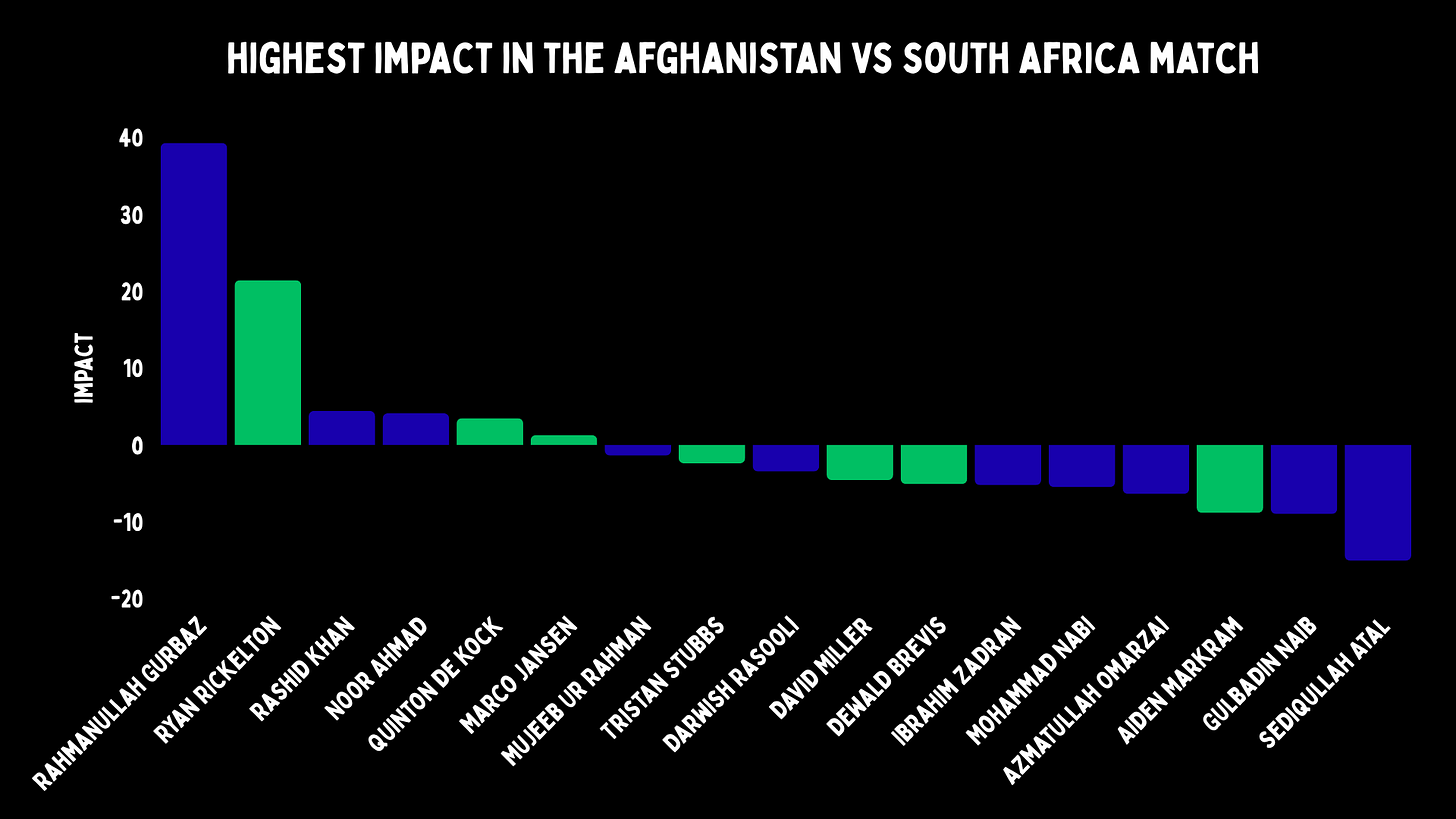

My reaction after it ended was that it’s one of the best innings I’ve seen live in a T20 World Cup. So I wanted to go through the numbers, and we turned to our impact metric.

Of all chases in T20 World Cups when Test nations played each other, it ranks 8th. We have the famous Marlon Samuels’ 85 in the 2016 final just ahead. Rohit Sharma and Lorcan Tucker versus Australia had an element of their sides never really being in the game despite their lone warrior efforts.

Jos Buttler’s 71 was an incredible knock, but it wasn’t challenging; they were chasing only 126. Matthew Hayden’s 58 in the 2007 edition was also in a similarly low target. Litton Das was the only batter who made any runs for Bangladesh in that chase of 116 (a game which is now remembered for Gulbadin Naib’s antics).

Chris Gayle’s 100 at Wankhede was perhaps the closest to what we saw today, as he was also an opener chasing over 180. But that was a decade ago, and the left-hander was unbeaten.

In this match, Gurbaz was well ahead of Ryan Rickelton in second place. If we look at per ball impact, Gurbaz was 0.94 while the latter was at 0.77. While he was at the crease, he made 69.4% of the team’s runs (including extras).

All of this just begs the question: why would you hold him back in the second Super Over?

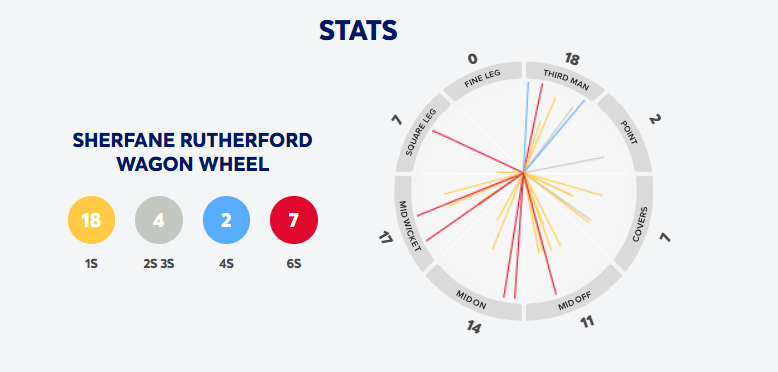

Sherfane Rutherford continues his insane run of form

Sherfane Rutherford is coming off an incredible season for Pretoria Capitals at the SA20. The left-hander scored 334 runs in 10 innings, averaging 66.8 at a strike rate of 165.3. His partnerships with Dewald Brevis rescued the team from situations like 7/5 in the 5th over and 89/4 in the 13th over, while also propelling them from 134/5 in the 16th over to 220/5 at the end. He also tonked a 24-ball unbeaten 57 against South Africa in the T20I series that followed.

Today, he came in right at the end of the powerplay, when the West Indies were three down and had lost the in-form Shimron Hetmyer. He was in India now, not South Africa. But his team was in a tricky situation, again.

After 9.3 overs, they were 77/4 after Roston Chase’s dismissal. At the end of the first middle overs (7-11), he was batting at 10 off 12. In the first innings of the recent SA20 season, he didn’t face too many balls in that period. But in the next two phases, he struck at 152.6 and 201.2.

Today, that was exactly 220 in both. After spending some time in the middle, he began to accelerate in the 12th over when England decided to bowl Will Jacks.

The English bowler he had faced the most in T20Is before today was Adil Rashid, and the numbers read: 21 runs, 31 balls, 3 wickets. Today, he scored 8 off 9 versus him. Rashid beat him with a googly in the 7th over. Even when the leggie came back in the 15th and 18th overs, he was happy to take singles. The only real boundary attempt was on the 5th ball of the 18th over, when he mishit a slog sweep and was dropped by Rashid himself.

He whacked seven sixes; all but one were on the legside. The midwicket to mid-on arc was quite productive for him. He did make the most runs in the third man region, but that includes a couple of edges that flew away for boundaries.

Overall, he struck at 223.5 versus pace and 152 against spin during his 42-ball stay at the crease.