I’ve always been annoyed that the mainstream outlets publish all their team analyses and previews on separate pages. Why can’t I just have one article to bookmark, and to come back to whenever I want a refresher?

So, I decided to make one myself. And, for some unfathomable reason, a bunch of elite cricket writers – who’ve already been writing for BoC during the WC – decided to help out. I’m sure you’ve seen some of their work over the first couple of weeks.

Dom Murray (Beyond Cow Corner) and Ben Brettell (Cricinspo) are our in-house NZ & ENG specialists respectively, Arnav Jain’s been explaining how to use his incredible Field Toolkit dashboard, and there are multiple other names that haven’t had a chance to contribute yet. Well, until now.

So, obviously, instead of being grateful for their contributions, I’ve decided to work them like a slave-driver. It’s paid off with what I think is the single best set of analyses on all the Super 8 teams.

These are stories that should be read before the stage kicks off, but also can be read before each team’s games. I promise it will give you something unique to look for every time you flip on any match.

So, enough with my awe-struck rambling, and on to our All-Stars’ writing. Oh, and I’d stick around until the last piece. It’s a pretty fun exercise in whether we can start inventing advanced metrics to understand the game better.

I would suggest reading them all, but you can also jump to your team first;

-

🌴 | WEST INDIES: Shubh Agarwal on how WI’s poor powerplay batting has been papered over in their dominant group stage run.

-

🇿🇼 | ZIMBABWE: Raunak Thakur on ZIM’s brilliant top order and pace trio, and their untested, inexperienced and fragile lower order.

-

🇮🇳 | INDIA: Arnav Jain looks at the advanced stats at the margins around India’s stars; the strengths and weaknesses of their elite role players.

-

🇿🇦 | SOUTH AFRICA: Tarutr Malhotra on QdK’s underperformance, which has oddly not hampered SA’s top order batting. Yet.

-

🏴 | ENGLAND: Ben Brettell thinks ENG can easily qualify for the knockouts, if their big names just play at an average level instead of being terrible.

-

🇵🇰 | PAKISTAN: Shubh Agarwal on the PAK batters’ ironic struggles with spin, and the complete unsuitability of their pacers.

-

🇳🇿 | NEW ZEALAND: Dom Murray on NZ’s brilliant batting and desperately bad bowling that either wins or loses them the game in the first 15 overs.

-

🇱🇰 | SRI LANKA: Kartik Kannan invents a few metrics to figure out if SL are a real contender, and if they have been unfairly dismissed for just being SL.

(Note for my email subscribers; these internal links only work on the website because Substack is a stupid platform. Considerately, I’ve made this article is too long for your email, so you may as well come join us outside your inbox this time around.)

If you’re reading this online, remember: you can get it via WhatsApp or direct to your email👇!

✍️ Written by Shubh Agarwal, an ex-analyst at ESPN & Cricket.com. Follow him on X.

West Indies’ smooth sailing through the group stage has been a nice surprise. They defeated the associate nations without any jitters, and trumped England by a fair margin.

However, they are a volatile side that may have peaked early. In the previous edition at their home in 2024, they won only one of their three Super 8 games – against USA – after clean sweeping their group. While they have the momentum, the next phase will ask tougher questions.

One of those questions revolves around their powerplay batting numbers – one of the few boxes West Indies didn’t tick in the group fixtures. The Caribbean batters have averaged 27.33 at a strike rate of 113.89 in the first six overs. The average is the second lowest and the strike rate is the lowest among all teams that have qualified for the Super 8s.

Brandon King’s form is a big reason behind West Indies’ struggle to get off the blocks. King averages 14.33 in the powerplay at a strike rate of 93.48, getting dismissed three times in this phase in four innings. Among batters from Full Member nations who have faced 20-plus balls in the powerplay this World Cup, King and Ireland’s Harry Tector (86.96) are the only two batters with a sub-100 strike rate.

In addition, Shimron Hetmyer hasn’t enjoyed batting with the fielders around him. The left-hander has been dismissed twice in the powerplay when he has been summoned early. Skipper Shai Hope averages 72 in this phase but has struck at only 124.14. Roston Chase 114.29.

West Indies are lined up to play India, Zimbabwe and South Africa in the Super 8s. All three of these sides have yielded penetrative results in the first six overs. Zimbabwe have the best bowling average in this phase (13.67) while India hold the best economy (6.75). South Africa have snaffled the most wickets (12) alongside an average of 17.33 runs per wicket.

West Indies could find themselves under early pressure in the Super 8s unless their powerplay returns improve quickly.

However, getting past this vulnerability opens the door to dominance for West Indies. Once the field has spread, the Caribbean batters have been a tough bunch to contain.

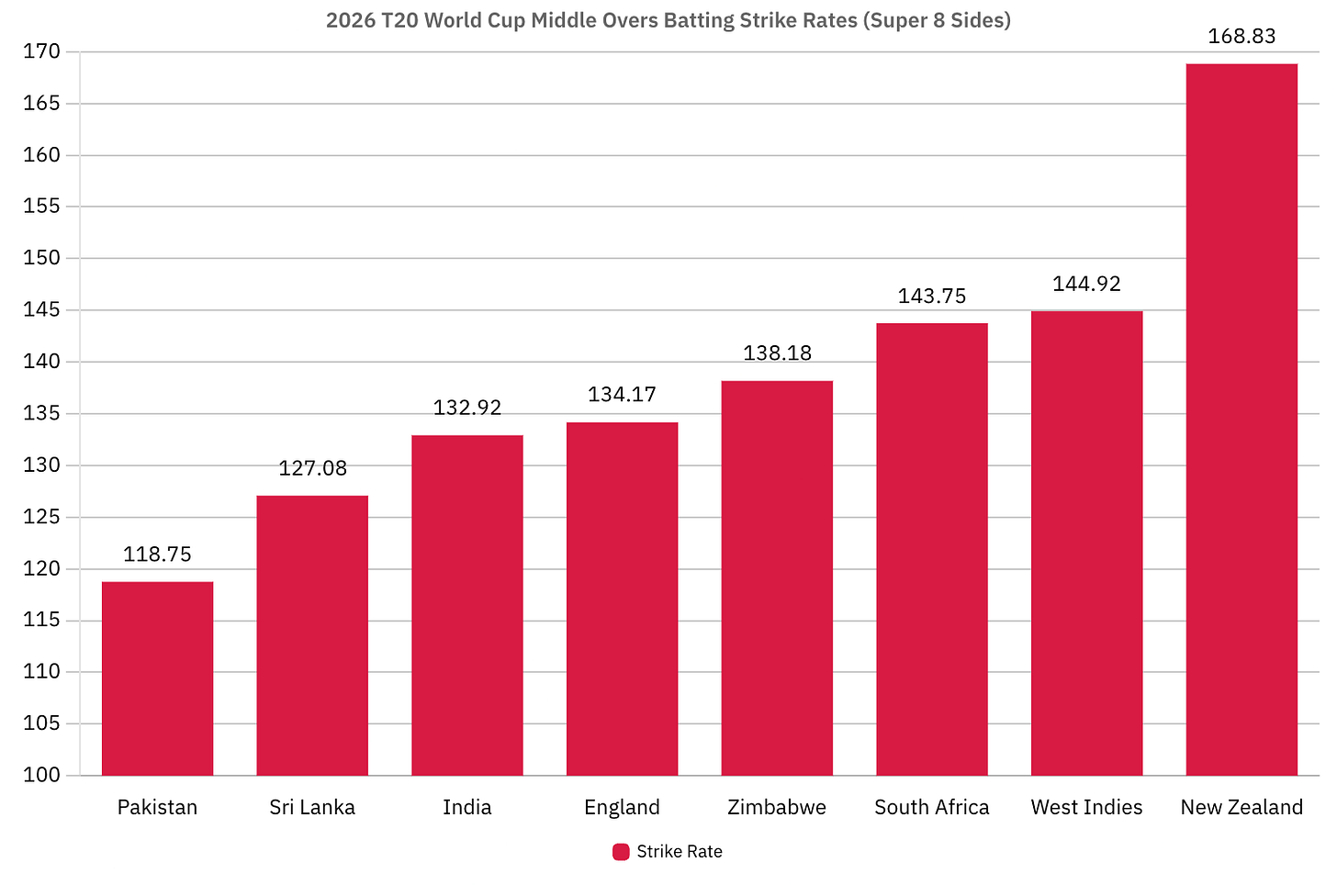

Among Super 8 teams, they have the third-best average (42.75) and the second-best strike rate (144.92) in the middle overs. In the death overs, they have the third-best strike rate (197.22).

Overall, they have been among the best batting sides when the field is spread. The fact that both Hetmyer and Sherfane Rutherford are averaging 40-plus at a strike rate in excess of 150 has helped West Indies to overcome sluggish starts.

The bowling has been a collective effort, with a new hero in every game. Romario Shepherd snapped 5/20 against Scotland, Jason Holder picked up 4/27 versus Nepal, & Shamar Joseph took 4/30 against Italy. The spinners ruled the roost against England as Roston Chase and Gudakesh Motie picked five wickets between them.

However, West Indies may need to change their bowling composition in the Super 8s.

They have backed two left-arm finger spinners – Motie and Akeal Hosein – in all four group games so far. But India and South Africa have three to four left-handers in their top six that may put this combination under pressure. It is a match-up that doesn’t favor the left-arm spinners. The numbers also suggest West Indies prefer keeping both away from left-handers.

The Men in Maroon could consider bringing in Jayden Seales, who averages 44.42 at an economy of 10.36 in nine T20Is since December 2024, leaving their bowling attack somewhat vulnerable.

Their smooth journey in the group stage is set to face the sterner winds of the Super 8s, and just rowing their oars may not be enough anymore.

If you’re reading this online, remember: you can get it via WhatsApp or direct to your email👇!

✍️ Written by Raunak Thakur, who runs Dead Pitch’s Society. Follow him on X.

With their team marred by injuries, Zimbabwean fans would’ve been forgiven for booking early tickets home.

They lost both Brendan Taylor – an icon of Zimbabwean cricket and a key batter in their line-up – as well as Richard Ngarava – a major presence in their lethal pace trio – after their one-sided opener v Oman. Yet, despite these setbacks, they dominated a group with both perennial table-toppers Australia and in-form co-hosts Sri Lanka.

And they’ve done it with contributions up and down the order.

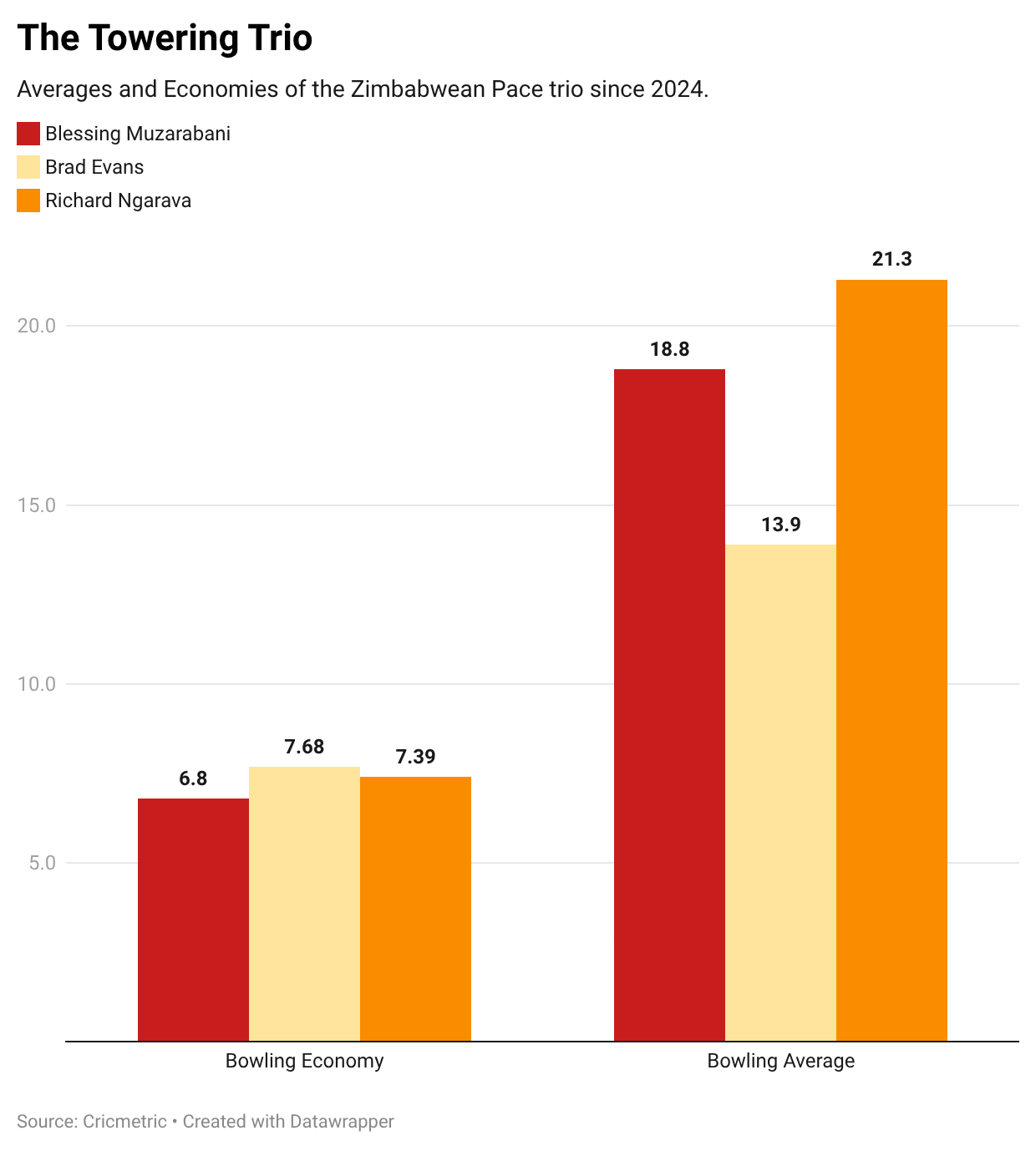

Zimbabwe’s pace trio of Blessing Muzarabani (6ft 8in), Brad Evans (6ft 2in), and Richard Ngarava (6ft 6in) have been the driving force behind their unbeaten Group B campaign. The sheer height across the board generates steep bounce that batters aren’t accustomed to on subcontinent pitches.

Additionally, their unique variations provide a secondary challenge to batters trying to get settled. Muzarabani’s seam movement and hard-length deliveries, Evans’s cutters, slower bouncers and yorkers, & Ngarava’s left-arm swing and awkward angles are a potent combination.

Unsurprisingly, all three have been devastating during the World Cup. Muzarabani has 9 wickets at an economy of 5.91, while Evans has 8 at and economy of 7.35. Meanwhile, Ngrava’s only played one game – where he took 3 wickets at an economy of 4.32.

Additionally, if ZIM’s opponents play out the pacers, they have to contend with Ryan Burl; a part-time spinner with a golden arm who keeps taking key middle over wickets.

Against Australia, introduced in the 14th over, he tempted Glenn Maxwell with flight outside off, drew him into the big shot, and shifted the momentum entirely. Against Sri Lanka, in a game shaped by spin, he entered in the 13th over and removed Kusal Mendis almost immediately.

In his T20I career, Burl has been particularly lethal between overs 7 and 17. He averages just 22.3 while conceding a mere 7.12 runs an over – a sixth bowler who knows his craft and is ready to apply it effectively at every given opportunity.

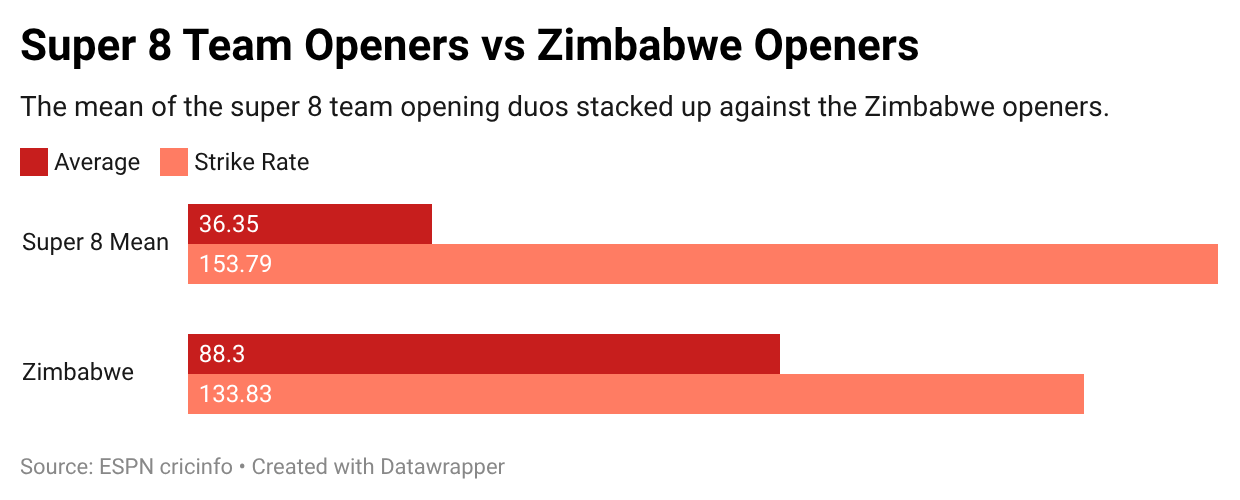

The opening pair of Brian Bennett and Tadiwanashe Marumani have been responsible for the bulk of ZIM’s scoring. One drops the anchor, and the other goes on his merry swashbuckling ways.

Bennett has been ZIM’s invincible and stabilising presence so far, playing through the innings in all three games. His 175 runs have come at a SR of 125, with a boundary every 6.36 balls and a boundary percentage of 15.71%. Those sound like bad T20 numbers, but he’s been elite with his running. 87 of his 175 runs have come in pesky singles and doubles, running hard and rotating strike at a non-boundary strike rate of 73.73. The ideal anchor.

Marumani, on the other hand, is the polar opposite. Striking at 155.17 with a healthy average of 30, he attacks from ball one in the powerplay and the numbers reveal just how boundary-dependent his game is. With a boundary every 3.22 balls and a boundary percentage of 31.03%, he hits the ropes at regular intervals. His non-boundary SR of 40 reinforces this strategy: he’s going for boundaries or bust. The ideal aggressor.

Ryan Burl steps in at three following the setback of Brendan Taylor’s absence and sticks with the high intent, striking at 138.10. His boundary percentage of 16.67% and a boundary every 6 balls are comparable to Bennett’s, but his non-boundary strike rate of 80.00 shows he’s equally dangerous between the 22 yards. Bennett’s solidity on the other end lets Burl play his natural game, and accelerate as when needed without run pressure.

And, skipper Sikandar Raza is the ideal finisher. He’s going at a SR of 182.93, a balls per boundary of 4.1, and a boundary percentage of 24.38%. That last bit is important – despite having already hit five 6s, Raza isn’t just slogging. His non-boundary strike rate is 80.65 – the highest of the 4 batters who’ve formed the spine of their attack.

The flipside of a fantastic top order is that the rest of ZIM’s batters have faced just 6 balls this tournament. In those 6 balls (all against SL), they conceded a late wicket to tease the hint of a collapse, before Bennett calmly took the. home. For the sake of balance, it should be noted that Tony Munyonga also hit a 6 in his 3 deliveries.

However, the numbers aren’t kind beyond that easy finish.

Dion Myers is a No.3 dropped down the order to accommodate the working top order. He strikes at 134.7 in his regular position, but just 112.5 in his 5 innings lower down. Tashinga Musekiwa is a handy hitter with a T20I career strike rate of 136.8 but has limited exposure vs ZIM’s Super 8 opponents. He’s averaged just 4.5 in two innings versus South Africa. And Munyonga – despite that big 6 v SL – has a career SR of 107.1.

For now, it’s not been a problem as ZIM have cruised their two major tests. And, of all the qualifiers, they’re the one nation who can claim to have had as tough a test in the group stage as they will face in the Super 8s. There’s no counting them out, but a lot of this team’s batting fortunes rest on Brian Bennett continuing his Ironman form.

If you’re reading this online, remember: you can get it via WhatsApp or direct to your email👇!

✍️ Written by Arnav Jain, who runs CricBit. You can follow him on X.

The overall quality of this Indian side is obvious – the overwhelming skill of the players is their biggest strength. But, it’s worth delving into exactly what some of these players are doing well and badly if we’re going to figure out what counters the opposition can find.

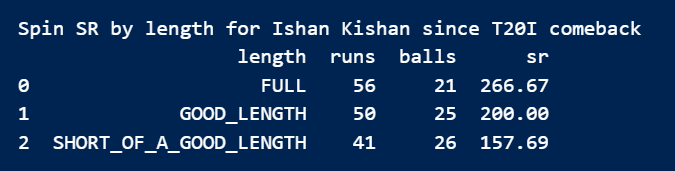

Ishan Kishan has always dominated pace in the powerplay but he is actually relatively more effective v. spin. His SRs vs full, good and short of good spin deliveries are 36%, 51% and 75% better than his partners on the other end of the pitch.

Kishan is also an excellent player of the slog sweep, a skill that Indian batters do not necessarily possess. Before he was reinstated in the Indian team, only Axar Patel had a better than average slog sweep percentage in the side.

On grounds like the Wankhede which are small and have offered turn this WC, Kishan can provide effective starts regardless of the bowlers thrown at him.

Shivam Dube has traditionally struggled against good length pace. Across his T20I and IPL career, he’s only struck at 115.7 versus the delivery. Unsurprisingly, it has also played on his mind; his intent (a metric based off his and his batting partners’ strike rates) is below average to both good and short of a good length deliveries.

However, in 2025-26, his strike rate versus good length pace has gone up a bit to 126.56. This may not be a standout jump (or even a huge number on paper), but it is important to contextualise Dube’s better hitting and intent.

At this length in this time period, his fellow batters have only managed a strike rate of just 108.53. It all means that his intent against good length balls has shot up from 0.9 (or 10% worse than his peers) to 1.13 (or 13% better than his peers).

This is a significant boost for India’s lower order, since it gives them a pace-happy hitter in a side where a lower order of Rinku Singh, Hardik Pandya and Axar Patel don’t have the best numbers against quicks at the death.

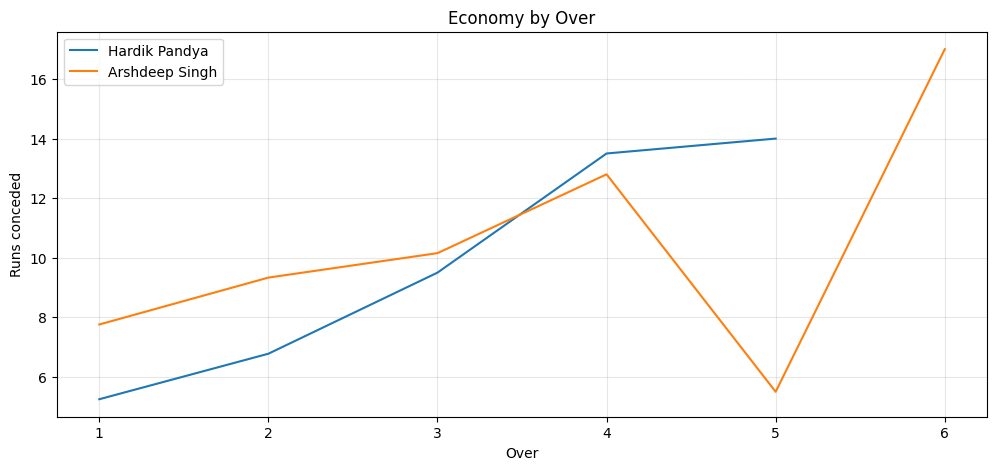

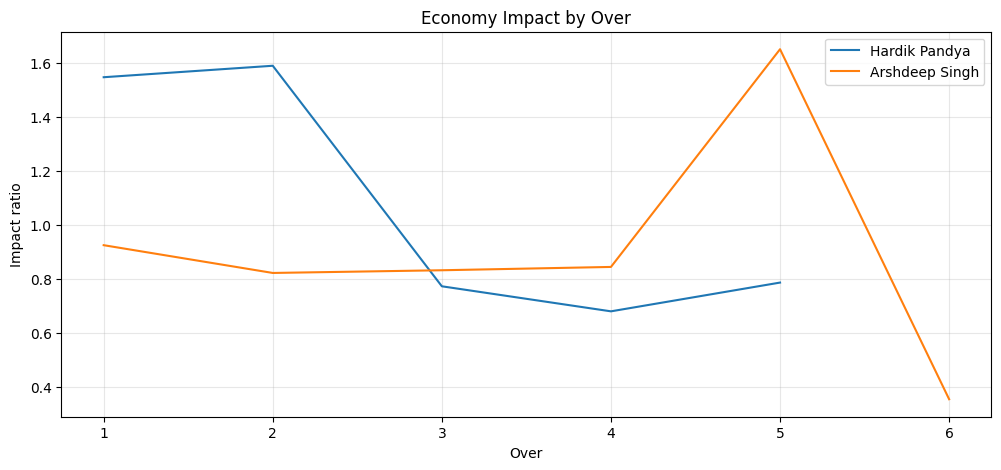

With a three pace attack (Arshdeep Singh, Jasprit Bumrah and Hardik Pandya), the new ball is often handed to Arshdeep in the expectation his swing will cause trouble. However, the data suggests that Pandya is the better option. His economy is just 8.5 compared to Arshdeep’s 9.01, and he starts the game better too.

Economy Impact measures how much better (or worse) a bowler’s economy was compared to his neighbouring overs. This plot shows economy impact progressions for Pandya and Arshdeep in PP;

Arshdeep has gone at 10.25 in the powerplay in 2026 in the 16 overs he has bowled. His economy impact in the PP has taken a fall from 0.96 (which is 4% below par) in 2025 to 0.7 in 2026.

India need to rejig their opening partnership to adhere to this advice, or they will be giving the opposition easy runs at the top that may prove costlier as we reach the serious end of the World Cup.

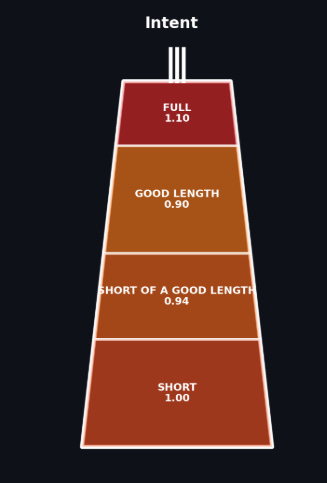

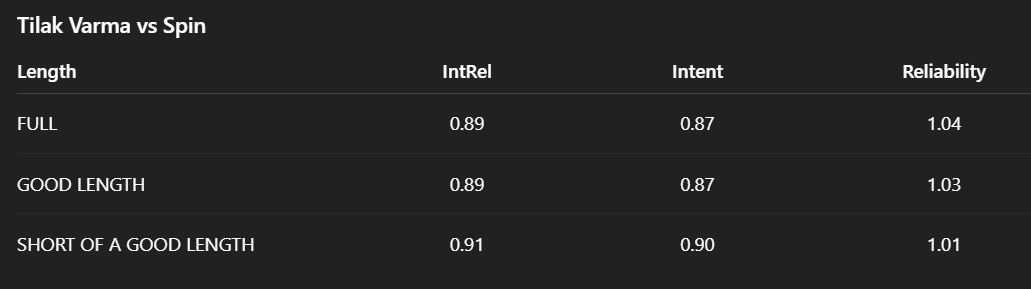

While Tilak Varma’s strike rate of 127.7 against T20I spin since the start of 2025 makes for uncomfortable reading, it actually gets worse when you dig into the numbers.

In both internationals and IPL T20s, Verma has struck well against fuller deliveries (156.25), but poorly against good length (105.06) and short of a good length (107.25) balls. However, that number belies his intent; despite the good strike rate, his intent has been poor against all three lengths of spin bowling. His intent is at 11%, 11% and 9% worse compared to his partners on the pitch.

This extreme cautiousness doesn’t even translate to more control. His reliability (a relative measure of his control percentage) is barely above par for all three lengths, as the below table shows. A stat of 1 equates to an average performance against these deliveries as compared to his peers on the pitch.

Varma is a good sweeper, which makes him a key batter on pitches where the ball sticks in the surface and comes late on the bat. However, that skill is undermined by his low intent, which allows spinners to put the pressure on him as India get out of the powerplay and into their lower scoring middle overs phase.

If you’re reading this online, remember: you can get it via WhatsApp or direct to your email👇!

✍️ Written by Tarutr Malhotra, who runs Best of Cricket.

Quinton de Kock has been a revelation for South Africa since his un-retirement. In just 14 innings, he’s rocketed up to become SA’s third highest scorer in the team since the start of 2025 with 448 runs at an insane strike rate of 167.79.

However, at this World Cup, QdK has struggled. Apart from one great innings versus Afghanistan, he’s scored at just 113.46 in the tournament (and just 126.88 even with that game in mind). I dug around his numbers to try and figure out what was going on, and there’s one big difference; his six-hitting.

Since coming back, QdK has scored boundaries at a phenomenal rate of one every 3.93 balls. That’s easily the best figure in this South African side. The 4s have stayed largely steady; 3.1 a game since September, and 3.3 a game in this World Cup (from more average balls faced). However, the 6s have plummeted; since un-retiring, he’s scored 1.8 maximums a game, but in this tournament that’s dropped to just one 6 per game.

That doesn’t sound like a big difference on the scoreboard, but it is a huge difference on the pitch. If QdK can’t threaten to clear the fences regularly, bowlers can be a lot more aggressive against him. Unsurprisingly, he’s been caught on the boundary twice and bowled looking for a big shot twice in 4 World Cup innings.

This slump matters because QdK has been SA’s third highest scorer since the start of 2025. Unfortunately for them, their highest scorer in the last 14 months is also having a terrible time at this World Cup.

In 2025, Dewald Brevis scored 464 runs at an average of 30.93 and an absurd strike rate of 176.42. Despite putting up monster numbers in the SA20 at the end of the year, his form has dropped off a cliff in 2026. This year, he’s only scored 107 runs in 6 innings, at an average of 17.83 and a strike rate of 128.91.

It’s not very clear why his form has tailed off, but there could be a clue in his 2025 performances. His numbers were heavily boosted by an incredible innings of 125* (56) against Australia in August, but he only scored one other half-century in 16 innings.

Additionally, when you break it down by opposition, Brevis averaged above 30.93 versus just two teams in 2025; Australia and Zimbabwe. In SA’s warm-up series for the World Cup this year versus West Indies, he averaged a measly 10.5 with a high score of 17 despite SA easily winning 2-1.

And yet, despite these two key batters going missing, SA have scored at 9.94 runs per over in the World Cup. That’s the second highest rate of any side at this World Cup (not just the Super 8 sides). In particular, they’ve been awesome at the start, a phase where you would assume an underperforming No. 2 and No. 4 would slow you down.

In the powerplay SA score at 10.33 RPO, in the middle overs they score at 9.84, and at the death they score at a surprisingly low 9.45. These numbers are largely down to the two other players in SA’s top order; Aiden Markram and Ryan Rickelton.

The duo have scored nearly half of SA’s runs this tournament (48.21%), and they’ve done it quickly. The skipper has scored at 187.36, while Rickelton has been even more impressive at 190.78. Amongst the other top 25 run scorers in the World Cup group stage, only Ishan Kishan has scored at a faster rate (202.29).

Which is amazing, but also problematic. QdK and Brevis were two of the three best batters in South Africa’s T20I tour of India last December – and they still lost 3-1. Similarly, QdK was the best performer by far versus West Indies in their warm up series, scoring 143 runs at 226.98 in the two games SA won.

In between those two series, Rickelton has stepped up his game. He’s become a genuine all-weather option at the top, and it’s shown this World Cup. Despite their theoretical slew of finishers – all of whom are performing at basically the same or better rates than their 2025 numbers – SA are a top-heavy team. At the moment, only half of that top 4 are pulling their weight.

So, the question remains; are QdK and Brevis going to pick up the slack against teams they’ve performed well against in the past 14 months? Or, is their terrible form going to be too much for Markram and Rickelton to cover up for in the more cutthroat Super 8 phase?

If you’re reading this online, remember: you can get it via WhatsApp or direct to your email👇!

✍️ Written by Ben Brettell, who runs Cricinspo.

Tournaments are won at the end, not the beginning.

England made a nervy start, and must’ve believed they would lose to Nepal before Sam Curran nailed that final over. A disappointing performance with bat and ball followed against West Indies to heap pressure on the two remaining games.

The media sensationalised both the Scotland and Italy games as near-losses, but in truth, England never looked like losing either. Winning is what matters, not how you get there. The super eights is a clean slate, and England will fancy their chances of taking this tournament deep.

Nevertheless, I can see reasons for both optimism and pessimism from here.

England have qualified comfortably without their best players hitting top gear. Jos Buttler has had a shocker so far, with just 56 runs across the four games. But the class of England’s greatest ever white-ball batter isn’t in doubt – he has more than 4,000 runs in the format, and he’ll come good at some stage. Meanwhile Phil Salt has just 60 runs and Harry Brook just 88.

With the ball, England’s two bankers – Adil Rashid and Jofra Archer – have both been uncharacteristically expensive, going for more than nine an over. Rashid being taken down by Italy’s Grant Stewart was hard to watch from an England perspective.

It’s to England’s credit that they have enough depth for other players to pick up the slack. Jamie Overton has been their best bowler, picking up six wickets at 12.3 and going at just over a run a ball. Curran held his nerve at the death against Nepal. Banton took control of the chase against Scotland.

All it would take is for the performances of Buttler, Salt, Brook, Rashid and Archer to revert to the mean, and England would suddenly be firing on all cylinders again. With arguably the easier of the super eight groups, and Sri Lankan conditions they’ve had recent acclimatisation to, England should really qualify for the semis.

Yet I have a few nagging doubts. I’ve written about England’s powerplay bowling problems before. Since the last World Cup they’re ranked worst of the 20 teams, conceding 57.0 runs on average in this phase. They lack a settled partner for Archer and lack a cohesive plan.

They also lack bowling depth. With just three seam options, Archer, Overton and Curran, Brook has nowhere to turn if Rashid and Dawson are being hit. The part-time bowlers are just that – throw the ball to Jacks or Bethell and you’re usually relying on a mistake from the batters.

Another concern is the batting order – it seems like most players are slightly out of position, Tom Banton being the obvious example.

Across all T20s, Banton averages 26.2 and strikes at 143 when opening. At 4, his numbers are somewhat worse, averaging 24.2 and striking at 130. He’s only batted in the position 18 times, whereas he’s opened on 159 occasions. Should he open alongside Phil Salt, with the out-of-form Buttler shuffled down the order?

Also, I have a hunch that Brook is a place too low at 4. He’s a phenomenal striker of a cricket ball, and I want him facing as many deliveries as possible. I think England should consider swapping him with Jacob Bethell, a versatile player who can slot into almost any role. My preference would also be to swap Curran and Jacks. They have similar averages but Jacks has the higher strike rate (146 vs. 130) and is clearly in great touch.

A batting order of Salt, Banton, Brook, Bethell, Buttler, Jacks, Curran would make most sense to me.

There are parallels with Australia here. A lack of bowling depth, part-timers bowling crucial overs, and batters playing out of position were the key reasons for Australia’s group stage exit. There are some tweaks for England to consider.

Looking at the tournament betting, England are third favourites at 8/1, behind India and South Africa. For a talented team yet to hit top form, but with some structural issues, that seems about right to me.

If you’re reading this online, remember: you can get it via WhatsApp or direct to your email👇!

✍️ Written by Shubh Agarwal, an ex-analyst at ESPN & Cricket.com. Follow him on X.

Known for their unpredictable nature, Pakistan have been quite predictable in the group stage of this World Cup. All their strengths and weaknesses have panned out as predicted before the start of the tournament: the batting has mostly flunked, sometimes embarrassingly, while the spin bowling remains their best hope.

Sahibzada Farhan has been the highest run-scorer amongst all teams in the group stage, putting away 220 runs at a strike rate of 164.17. But no other Pakistani batter has even reached triple digits, with Shadab Khan accumulating 88 runs. Their middle order (numbers three to six) has averaged 18.78, higher than only Namibia and Oman’s middle order.

They have the advantage of Sri Lanka’s venues to play all their games at, and it’s an advantage that suits their potent and diverse spin attack. They can play as many as five spinners if they want, but it runs into an expected problem – the double-edged sword of the impact on their team composition and already weak batting order.

Ironically, the country’s batters have a tendency of slowing down against spin. In the build-up to this World Cup (January 2025 onwards) Pakistan had a strike rate of 124.85 against spin – only the eighth best among the 12 Full Member nations. That timidness has reflected in this World Cup. Pakistan’s average of 22.08 is the second-lowest average against spin among all the Super 8 teams. Meanwhile, their strike rate (122.69) is the lowest.

Surprisingly, India have quite comparable numbers with Pakistan on this metric – average 19.67, strike rate 12.92. However, India compensate by going quick against pace at an average of 27.27 and a strike rate of 179.39. Pakistan average 19.60 vs pace, the lowest among Super 8 teams and a strike rate of 138.03, the second lowest.

Pakistan’s strangulation against spin is a self-inflicted undoing, orchestrated by the move to play Babar Azam at number 4.

Like number 3 in Tests, number 4 is the trickiest position to bat in T20 cricket. Teams often prefer a dynamic batter at this spot who can showcase all batting gears at his arrival to the crease, irrespective of the bowling type against him. Pakistan chose Babar for this role, whose T20 game is on a steep decline. To add to it, the last time Babar batted at 4 in all T20s before this sudden move (which was initiated in the warm-up series against Australia) was way back in the 2018 edition of the Pakistan Super League (PSL).

Babar has traditionally been among the slowest starters in T20 cricket. Since 2025, he has a strike rate of 78.89 in the first 10 balls of his innings. That number is quite poor without requiring any comparison. Against spin, which he would be facing a lot as a number four batter, he strikes at only 66.67 at the start of his innings.

This World Cup, eight batters have a strike rate of 75 or lower in the first 10 balls of their innings. Three are from Pakistan, including Babar at 72.7.

Against Netherlands, his 15 off 18 balls brought the run chase to a standstill. Against USA, he was 7 off his first 10 balls before accelerating later on for a brief period. He scored 5 off seven balls against India. Babar hasn’t hit a boundary in the first 10 balls of his innings this World Cup.

Thus, Pakistan’s timidness versus spin is intertwined with Babar batting at four. And it should come as alarm bells given Pakistan will be up against the threat of Adil Rashid and Mitchell Santner in the Super 8s.

The matchups here account for Fakhar Zaman’s inclusion in the side. Pakistan currently have a streak of right-handers from number three to six. Fakhar can break that monotony. He also has a much better record against Rashid and Santner.

Fast bowling is another facet where Pakistan leave a lot to be desired. In their defence, they have bowled only 21.37% overs of pace, the lowest among all teams in the group stage – nearly 13% less than Sri Lanka. However, Shaheen’s poor form is a huge concern. The left-arm seamer has three wickets in three games, averaging 33.66 at an economy of 11.22.

Known to be the best first-over bowler once, Shaheen has picked all his three wickets at the death. In fact, his powerplay numbers have been on a nosedive since 2023.

Pakistan’s other seam-up options include Naseem Shah who has been in modest form in T20Is since 2025 (six wickets in six matches, six wickets, 25.66 average, 8.8 economy), Faheem Ashraf whom Pakistan didn’t trust for a single over against India, and Salman Mirza who is the most inexperienced but in-form seamer for Pakistan since his debut in 2025 – 15 matches, 23 wickets, 15 avg, 6.33 economy.

Against Namibia, Pakistan benched Shaheen for Mirza. But in conditions when they would want to field three seamers, the opposition will feel confident attacking Pakistan’s seam-up options.

If you’re reading this online, remember: you can get it via WhatsApp or direct to your email👇!

✍️ Written by Dom Murray, who runs Beyond Cow Corner.

Analysing the Black Caps’ performances so far in this T20 World Cup has been oddly straightforward: their strengths are incredibly strong, while their weaknesses are glaringly weak, with little middle ground. As you’ll see, this is not a team that does things by halves.

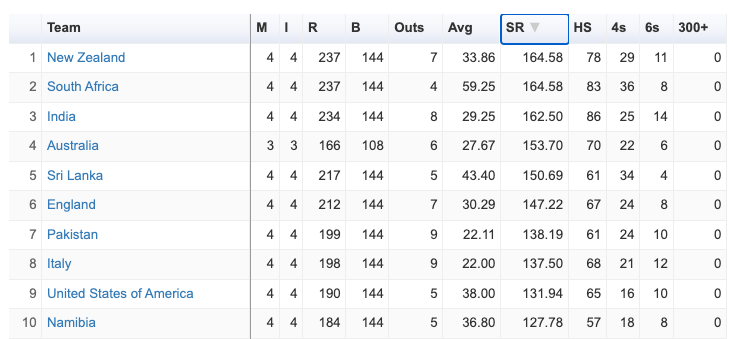

Across the 2026 World Cup group stage, no team struck faster in the powerplay than the Black Caps, who have motored along at 164.58, equivalent to a run rate of 9.87. South Africa equal this SR precisely, also scoring 237 runs off 144 balls in their powerplays, but no team betters it. Accordingly, the Black Caps have hit the second-most powerplay boundaries (40, behind South Africa’s 44).

However, the middle overs are where the Black Caps have really excelled in this tournament, standing head and shoulders above the other sides. Throughout the group stage, the Black Caps struck at 168.83 between overs 7 and 16, with the next-best strike rate being Scotland at 145.

To emphasise the gulf here, Pakistan struck at just 118.75 in the middle phase, the slowest of any Super 8 side, while even the fearsome Indian batting lineup ‘only’ struck at 133.

Somehow, this destructive middle-overs batting has come without sacrificing wickets. New Zealand have averaged 65 during this middle phase and lost just six wickets so far: no team has a higher average during this phase, while only Zimbabwe (4) have lost fewer middle overs wickets.

All told, across all phases, New Zealand have the highest strike rate (165.94) and second-highest batting average (49.1) of the remaining teams. Every member of their top 6 averaged at least 36 and struck at more than 150 during the group stage. Consequently, New Zealand have completed their 4th, 9th, and 11th highest successful T20I chases in this tournament, against Afghanistan, Canada, and the UAE, respectively.

All hail the batriarchy, let’s just finish the article here, no need to dig into their form on the other side of the ball…

While it’s a fantastic sign that New Zealand have completed three of their highest T20I chases in this tournament, questions must be asked about why the Black Caps had to chase such large totals to begin with, particularly against Canada and the UAE. Let’s examine it phase-by-phase.

Throughout the group phase, only Nepal (3) took fewer powerplay wickets than New Zealand (4), while Sri Lanka and Namibia took as few. By contrast, South Africa took three times as many powerplay wickets (12).

Only Namibia and Nepal took their powerplay wickets at a higher average throughout the group stage, while only Namibia took theirs at a worse strike rate, and only Ireland and Namibia had higher powerplay economy rates than New Zealand’s 9.46. Among Super 8 sides, the next-highest powerplay economy rate has been South Africa at 8.67.

Matt Henry’s numbers are the most concerning to me in this phase. While he has been economical, conceding 7.78 runs per over, he is yet to take a powerplay wicket, which is highly atypical for him.

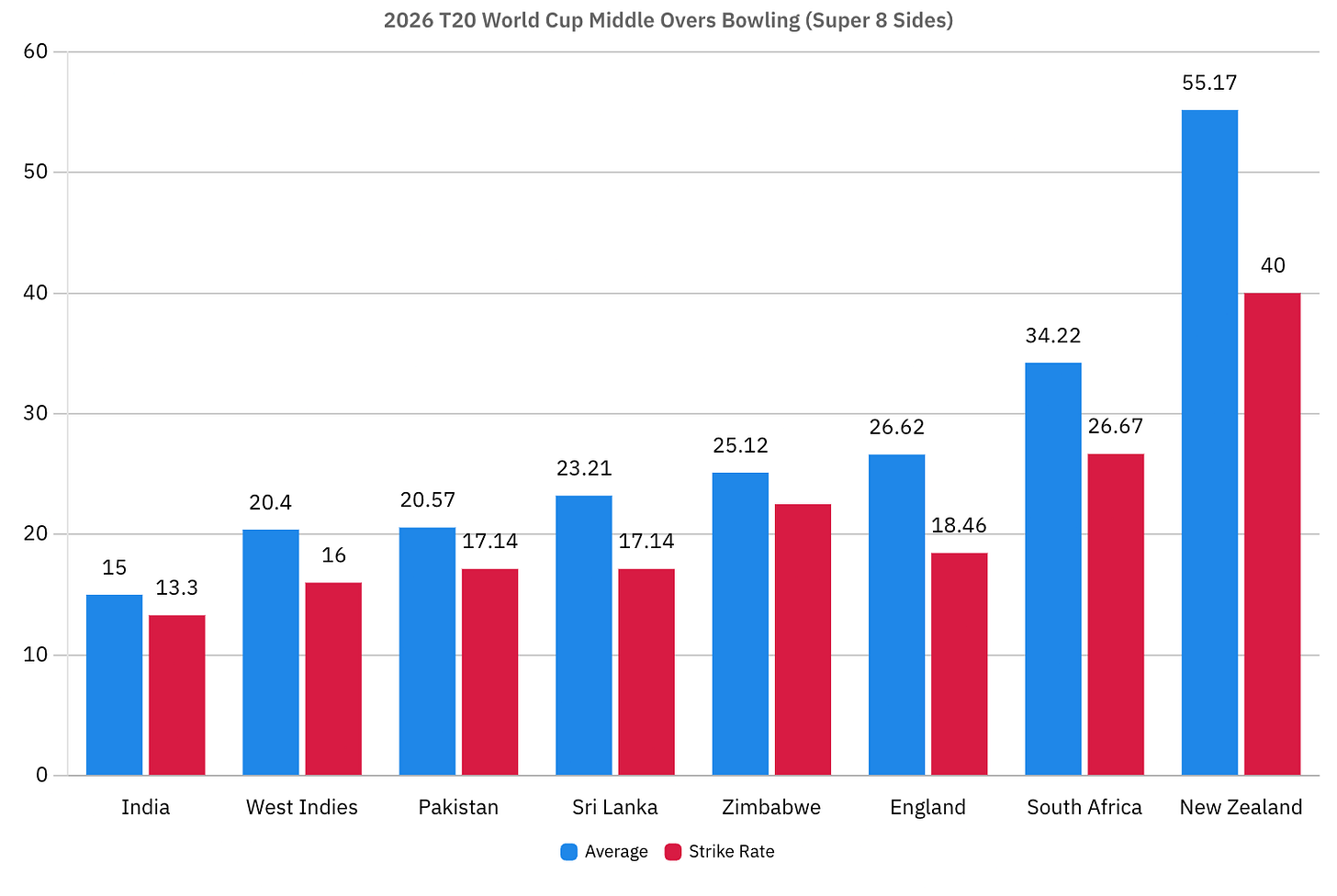

The story doesn’t improve for New Zealand’s bowlers in the middle phase. Throughout the group stage, only the UAE and Oman took fewer middle overs wickets than New Zealand’s 6. These were also the only two sides with worse averages and strike rates than New Zealand’s 55.17 and 40, respectively.

In terms of economy, the Black Caps ‘only’ rank 12th out of 20 in the middle overs, conceding 8.28 runs per over. However, of the teams below them, only England (8.65) qualified for the Super 8s.

The biggest concern in this phase is that no one has been able to consistently take wickets—six NZ bowlers have taken a wicket in the middle overs, but none have taken multiple. Santner and Neesham have been New Zealand’s most used bowlers in this phase, delivering 47.5% of the overs.

While New Zealand are better at picking up wickets at the death (9), this is of little value as they continue to bleed runs at an 11.24 economy rate, by far the worst of the Super 8 sides, with England, the next-worst, going at 10.79.

Across all phases, the Black Caps have taken just 18 of 40 possible wickets (with 50% of these coming at the death) at an average of 38.66 and an economy of 9.01. Among Super 8 sides, these are the worst bowling numbers in all three categories, and, in the case of bowling average, the worst by a significant margin.

Right now, our batting is flying, striking faster than any side remaining in the tournament, Mitchell Santner is his miserly self, conceding runs at 6.58 per over, Lockie Ferguson is bowling fast, and we’re just about getting away with a mishmash of Ravindra, Neesham, and Phillips as the fifth bowler (touch wood).

New ball wickets are very much the missing piece. If the Black Caps can rectify this issue, the sky is the limit in this tournament. If not, well, they won’t need to bother booking a return ticket to India.

If you’re reading this online, remember: you can get it via WhatsApp or direct to your email👇!

✍️ Written by Kartik Kannan, who runs the Long Rope Army. You can follow him on X.

30 years ago, I watched in awe as Lee Germon and Chris Harris lit up the Chepauk on a sweltering March evening. It was my first experience of a home World Cup – and it was an edition that changed everything for the island nation in particular.

Despite reaching 4 tri-series finals in 5 attempts prior to the World Cup, Arjuna Ranatunga’s men had gone under the radar. That 1996 team was ignored because they were “just” Sri Lanka. The 2026 team has been ignored because of their failures in the past two T20 World Cups – and because they’re “just” Sri Lanka.

They’re good, but even their hype-building victory over Australia was overshadowed by Zimbabwe’s heroics in the same group. So, can a deeper look at the statistics validate the local fans’ belief in the team?

-

Their bowling average (17.94) ranks 5th amongst the Super 8 teams – behind IND, PAK, NZ, & SA.

-

Their team bowling SR (13.46) ranks them 6th – not the quickest, but still effective as we saw in the wins over Oman and Australia.

-

Their batting average (19.74) ranks 2nd – excellent consistency with very few collapses and strong repeat performances by Pathum Nissanka and Kusal Mendis.

-

Their team batting SR (160.26) also ranks 2nd – very aggressive, especially amongst finishers like Kamindu Mendis (225.8 SR) & Dasun Shanaka (200 SR)

These are respectable, if not outstanding, numbers that back up the eye test. They’ve got a good batting order that’s firing, while their injured bowling unit is predictably the weaker link. However, we should go deeper with some advanced stats.

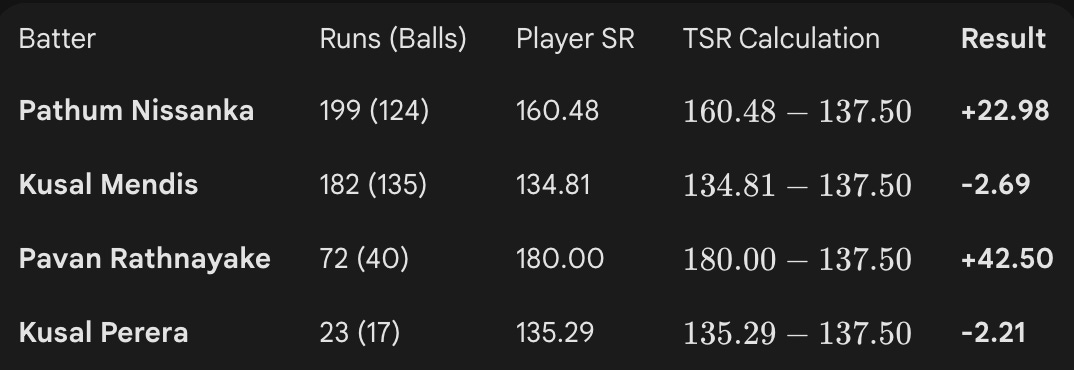

We can use True Strike Rate (TSR) – which measures a player’s strike relative to the everyone else in the World Cup – to understand whether the raw numbers look good when held up to the light.

With these advanced metrics, we can see exactly how SL’s batters and bowlers are actually performing;

-

Pathum Nissanka is operating in a different gear. A TSR of +22.98 suggests he is scoring roughly 23 runs more than the “average” batter for every 100 balls he faces.

-

Pavan Rathnayake has the highest TSR in the team at +42.5, despite playing relatively few balls all World Cup. He has played the role of impact finisher perfectly.

-

Both Kusal Mendis and Kusal Perera are playing below their peers, despite their seemingly high raw strike rates.

While Nissanka’s numbers in particular stand out for a player who’s carried the SL run-scoring burden, he’s coming up against the 3 of the 5 openers with a better TSR than him in the World Cup.

PAK’s Sahibzada Farhan (+25.97), NZ’s Tim Seifert (+29.76), & ENG’s Phil Salt (+23.9) have all played faster than him so far, but they’ve failed on more basic metrics. Neither Salt nor Seifert have displayed his consistency or control in the biggest games (Nissanka had 84% control during his 56-ball 100 v AUS!), while Farhan’s outlier brilliance is undercut by the rest of PAK’s poor batting.

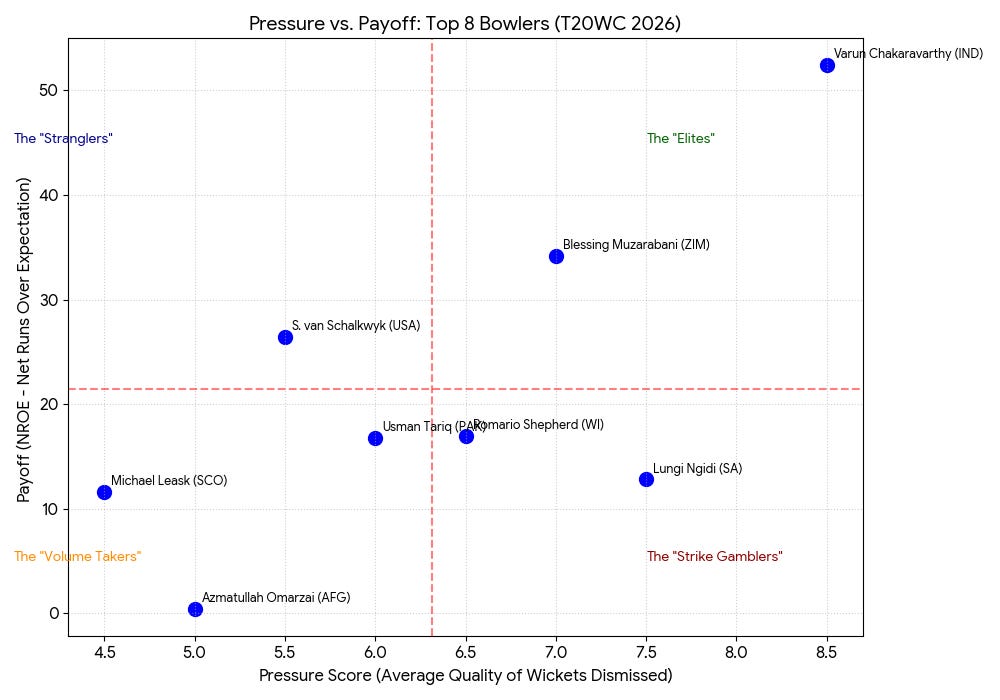

To determine bowling quality, it’s useful to look at two metrics; the economy-tracking “Net Runs over Expectation” (NROE), and the wicket-tracking “Pressure Score”.

NROE measures a bowler’s economy compared to their peers (i.e. how many extra runs did they save or concede compared to everyone else’s average economy), while Pressure Score measures the importance and difficulty of any given wicket taken (with top order batters weighted higher than lower order ones).

It sounds complex, but the question is simple – how much better are the SL bowlers at protecting runs and taking top order wickets compared to the rest of the competition?

To define that, first we have to define what good bowling has looked like in this WC.

A quick point on how to read this; a positive NROE is good (i.e. +10 means the bowler saved 10 runs), while a Pressure Score of over 6.4 is considered above average (i.e. the bowler has taken more top order than lower order wickets in general).

Shadley van Schalkwyk has made headlines for his 13 wickets, but when you look at the distribution of wickets you realise it’s maybe not as impressive as on first glance. He’s picked up a lot of middle and lower order bats.

Comparatively, Varun Chakravarthy has fewer wickets but of much higher quality batters, while also saving 52 more runs than the average bowler would’ve in his overs. Maybe you missed his dot. It’s way out there in the top right quadrant.

Now that we have a framework to judge “good” bowling, how do the SL bowlers compare?

-

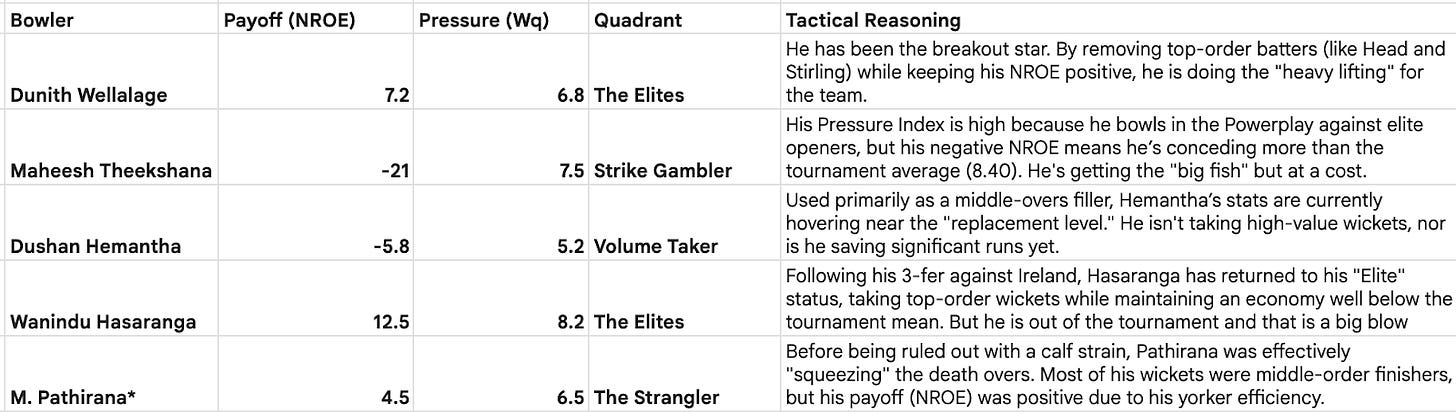

Sri Lanka is one of the few teams with two bowlers (Dunith Wellalage and Wanindu Hasaranga) in the “Elite” quadrant. This is why they are so dangerous in Colombo; they take the best batters out without bleeding runs.

-

Maheesh Theekshana is currently a “Strike Gambler”. For the Super 8s, Sri Lanka needs him to shift north into the “Elite” quadrant by bringing his NROE into the positives. If he continues to be expensive, the pressure on the middle-overs spin-web becomes unsustainable.

-

With Matheesha Pathirana out and Dilshan Madushanka (typically a “Strike Gambler”) coming in, Sri Lanka loses a “Strangler.” They will likely have to rely on their spinners to do both jobs—taking wickets and drying up runs. Additionally, they’ve lost another “Elite” in Wanindu Hasaranga and gained another “Volume Taker” in Dushan Hemantha.

This Sri Lanka side have been unfairly dismissed as making up the numbers because of their poor performances in 2022 and 2024, but there has been a huge evolution. Those sides were dependent on their bowlers to create opportunities. They needed perfection across the board to have a chance at winning games.

This time around, the growth of Pathum Nissanka into one of the world’s best batters has changed the equation. Despite the up-and-down performances from most of the batters in the group stage, SL never looked short of firepower because Nissanka and Rathnayake provided the hitting at either end of the innings.

However, injuries to two key bowlers – especially Hasaranga who’s become a genuinely elite prospect since the 2024 edition – is the biggest dampener. On paper, SL finally have options to fight the big boys. On the pitch, they’ve lost the wrong bowlers at the wrong times, and Wellalage’s heroics may not be enough to keep them in the running against true contenders.

Then again, none of the teams in Group B are true contenders. England, Pakistan and New Zealand all have their own flaws. There’s no reason to think SL’s underperforming stars in Theekshana and the two Kusals can’t provide the boost they need to get to the semifinals.

If you’re reading this online, remember: you can get it via WhatsApp or direct to your email👇!