Petor Georgallou wanders through missed moments and strange encounters to explore reality via cycling and film photography. Sometimes, slowing down and letting chance take the wheel can reveal deeper truths about our lived experiences. Take a philosophical detour with Petor and enjoy the ride.

“The world reveals itself to those who travel on foot.” – Werner Herzog

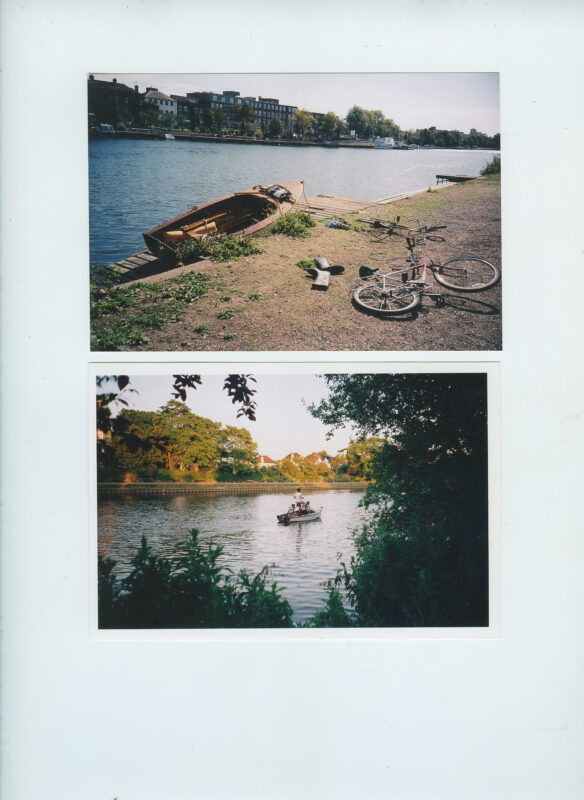

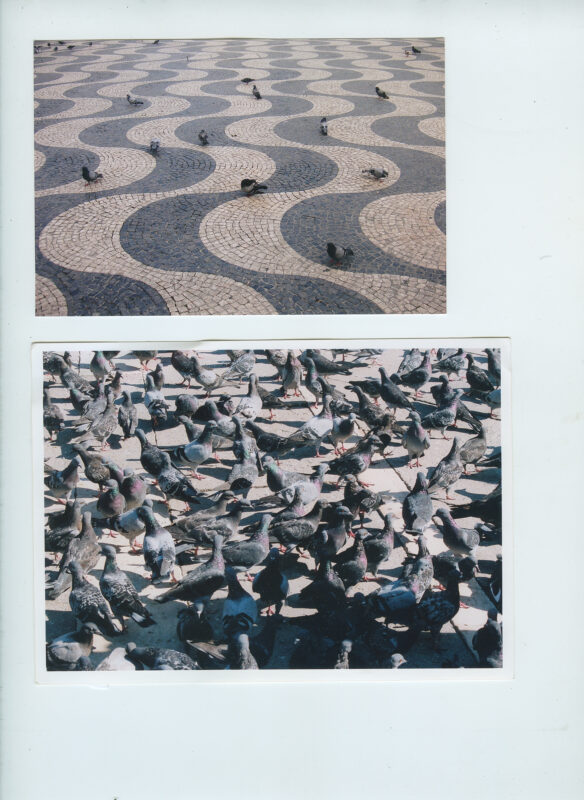

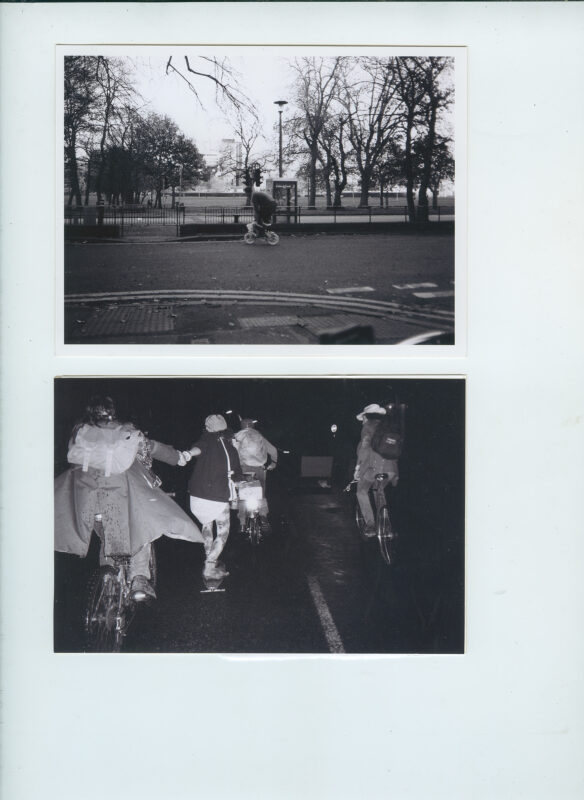

Perhaps this is why I have never really understood the world. Perhaps where pedestrian travel offers answers, travel by bike feeds curiosity. Travel by bike offers the widest selection of strangeness by covering the most ground while also being in the world, with the number of stops limited only by a personal expectation of reaching a destination. The cycling experience is more collage – or perhaps bricolage – with more source material than is manageable. It’s more chance than choice.

A Bicycle and a Camera

“Luck is blind, they say. It can’t see where it’s going and keeps running into people…and the people it knocks into we call lucky!” – Nikos Kazantzakis

A bicycle and a camera have to be the most efficient combination of tools to try to make sense of as much of the world as possible, as quickly as possible. The third leg of that tripod is time, and the thing in the middle that holds the legs apart – tripods don’t actually need it, but it makes them better – might be perspective. An iPhone doesn’t count, and a digital camera is a blunt and degraded version of the original tool, because film facilitates both a greater chance for failure or abstraction and, more critically, distance between seeing and re-seeing. Disorganization, chaos, and curiosity are friends with luck, and hang out at the same bars and cafés as creativity, failure, insoluble ideas, and the divine. Facts and numbers work in an office across the street, and they hate the music and feel alienated from the culture of curiosity and her friends.

The idea of a linear and consistently progressive narrative is the absurd ideal of a sportive – it’s not travel. It doesn’t leave any space around the mission for misinterpretation. It’s a solemn, blinkered march, whereas travel by bike is like a nursery rhyme or a dream: flirtatiously rhythmic and fleeting, which could have some deep and abstracted meaning clinging by a thread to a shared consciousness, or some stirring buried in our epigenetic makeup, as easily as being something you ate.

The Butterfly Tree

Once I cycled past a tree in a flat, agricultural French landscape, following a disused railway line to Paris that was so densely covered in white butterflies that the tree itself was barely visible. I slowed down and craned my neck almost 180 degrees to take in as much as I could, for as long as I could without stopping. The group had no time for rubbernecking, and legs grew heavy with their scorn as I dropped off the back. I passed the butterfly tree and sprinted to catch them. I can’t remember where I was going or why, but I still regret not stopping to photograph the butterfly tree decades later. Imagine not having five minutes to look at a butterfly tree during leisure. Why are we here? The butterfly tree in the rearview mirror of my imagination must be at least fifty times better than the real object, and I must have taken a thousand mediocre photographs mourning the loss of that image.

The Train

Once, a long time ago, I cycled as fast as I could through London to catch the last train home to my parents’ house. I don’t know why I was in London or what I’d been doing that night. I missed my train, so I caught a train that stopped in Surbiton, which is just a short ride from their house. It was an older train, with orange handrails and more space. I’d had my bicycle powder-coated by the same company that powder-coated the rails, and in the same color, so that it would be camouflaged on an overfilled train during rush hour in case I needed to catch one. The train was almost empty, which was unusual even on a weekday for a final – or even penultimate – train out of London, so I took a seat opposite my bicycle and away from the other two passengers in the carriage.

Trains before smartphones were a different prospect entirely because sitting near a stranger meant being much nearer to a stranger. People would have conversations, especially at night when they were drunk or giddy from imbibing culture. I didn’t want a conversation or proximity to a stranger, so I sat where I could look at my bike and really consider it, unencumbered by the peripheral possibilities of a chatty drunkard’s eyeline.

The train stopped between stations, and the lights went out. A lady across the carriage exchanged a nervous glance with me. I looked away to make it clear I wanted nothing to do with her or her anxiety. The lights came back on again, but the train didn’t start moving for a while, and I was spared polite conversation for perhaps fifteen minutes. The train stopped again. It was dark outside, but I could just make out the leaves of unkempt but brutally trimmed bushes blowing outside as if they wanted to touch the windows but couldn’t quite reach.

“If all passengers do not return to their seats immediately, British Transport Police will be called.”

– Over the tannoy.

The anxious woman from the other end of the carriage got up and walked over to me. I worked hard to ignore her. She could see my struggle, but frenzied by her anxiety, past the point of propriety and social norms, she walked over and sat almost opposite me, next to my bike on one corner of a four-seat arrangement (four seats facing each other, the best seats the train has to offer, because on an empty train you can put your legs up and see your bike enough to make sure it’s not eloping with a stranger).

Thankfully, the train moved again before she’d had a chance to strike up a conversation. Then, thirty seconds later, it juddered abruptly to a halt, and the lights went out again. She swiveled her body in the seat to face me. She looked like she was on her way back from a party, but not a real party – maybe an office party. A sensible person cosplaying fun, clutching a big heavy black leather handbag that looked expensive and probably had a laptop and some fancy shoes in it, because the running shoes she was wearing were incongruous with both her rabbit-fur coat and office-specific skirt. Even drunk, she was practically vibrating with anxiety induced by the unplanned stops.

“Do you know what’s going on?”

As if I were an expert.

“No, this doesn’t usually happen.”

It became a conversation. She’d been at a work party – I can’t remember what the work was, but I remember it was in Soho because she’d stopped at Bar Italia for a coffee before catching the train. I remembered that because I also liked to stop at Bar Italia for a burned bitter espresso and an amaretti on the way back when I cycled home, and that shared oddball coffee spot helped me trust her.

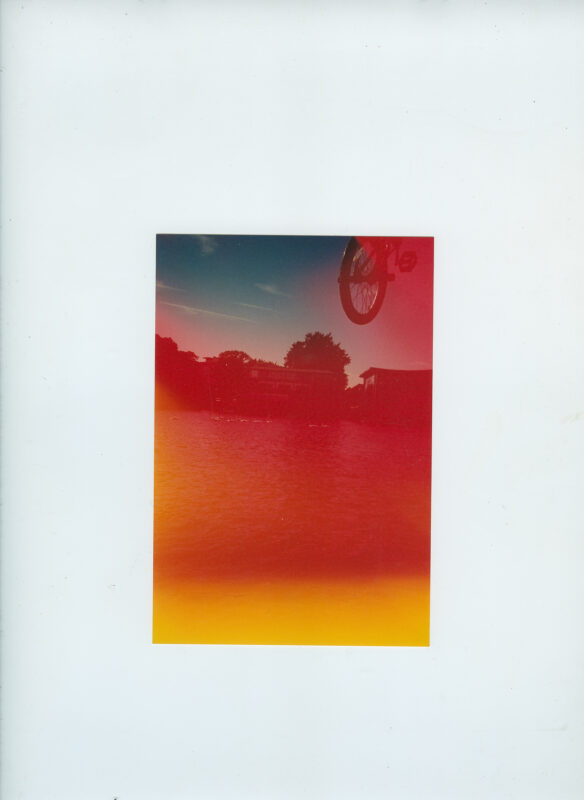

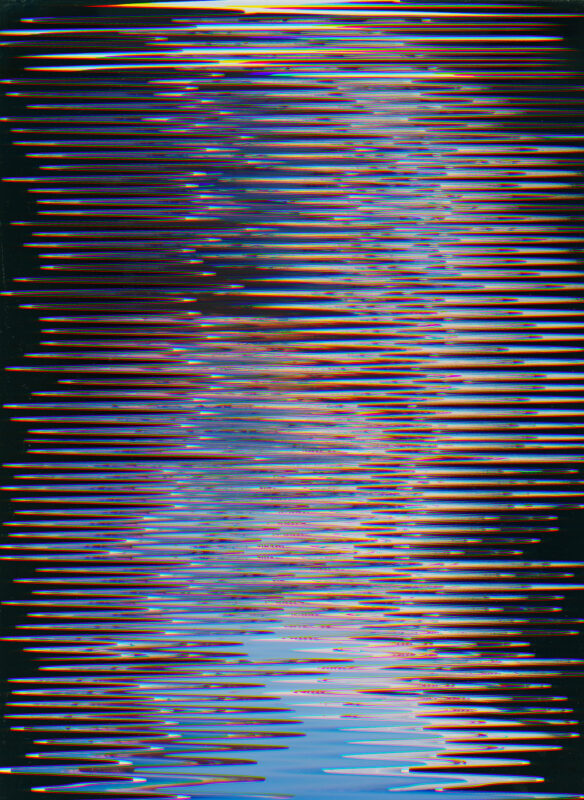

The train had stopped for a while, and she’d become less anxious through conversation, and I’d become less anxious because the conversation wasn’t as awful as I imagined it would be. We heard a low and rhythmic noise coming from the opposite end of the carriage that startled us both. The third passenger, from that end of the carriage, came and sat closer to us for safety, but not close enough to join our group. My hands were unemployed, so they searched around for something to hold to pass the time until I needed them again, and found a camera in my bag. Click, click, click, click, click. My forefinger clicked the lens cover of the LOMO LC-A open and shut nervously as the low rhythmic noise grew louder and closer. The camera had a weird cartoon character face on the front, which I hated, so I scratched it off; the metal underneath was slightly rusty and rough.

The noise grew closer and louder, and it sounded like voices chanting. Click, click, click, click – how far away is it? I set the focal distance to medium far away, ready for whatever was coming. Click, click, click, click – my lens cover flicking became faster. I couldn’t remember what film I’d loaded. Probably 800. Maybe 400. It was dark, but the lights were on, though they weren’t very bright. At 2.8, what is that? Maybe 1/30th? Probably 1/60th if it’s 800. 1/60th is fine. 1/30th might be okay. Click, click, click, click, click. Hmmm, hmm, hmmm, hmmm, hmmm, hmmm. The sound was almost at the door at the opposite end of the carriage.

“Haaaaaa, haaaa, hammm, hmmm, hammmm, hmmm, hello, hello, hello.”

The door at the end of the carriage opened, and we could hear it clearly. A rhythmic chanting.

“Hello. Hello. Hello.”

It seemed like all of the passengers from the rest of the train, who were a weird mismatched gaggle – clearly not together, or part of a group in any capacity – were crawling in human centipede formation, chanting “Hello. Hello. Hello.” The man at the front was wearing a grey suit and rhythmically dragging a brown leather briefcase along the ground. The teenage girl behind him in baggy flared blue jeans, frayed and dirty at the bottom, was staring solemnly, transfixed as if calculating complex sums in her mind, at his stripey grey bum, which was three inches from her face. I stood up and leaned into the aisle. Their line extended back through the whole next carriage, through the double doors into the next carriage, crawling and chanting hello in unison. Even the way that they were crawling was strange. The right leg and right arm moved together on the first syllable “HE” and the left followed on the second syllable “LLO,” then a pause, then right “HE” then left “LLO,” which is not how people crawl. All in unison with military precision – thirty or forty completely unrelated late-night commuters, transfixed, in some kind of trance. “HE,LLO, HE,LLO, HE,LLO,” right and then left, inching towards our terrified group in the bicycle section before the last bank of seats at the opposite end of the carriage at a rate of six inches per syllable. I stared dumbly for several cruel, dragging seconds before I could raise the Lomo to my face. Then, without really framing up properly, click. I took a picture.

I tried to wind it, but the camera stopped mid-stroke. The little frame-counter bubble read 38 (the LC-A is a short-bodied camera, so sometimes it gets more than 36 out of a roll). I stood and stared, pulsating and breathless, adrenaline sweat beading under my shirt collar and soaking the cotton. There is nothing in nature, and therefore nothing in my genetic makeup or experience, to guide me as to whether the appropriate response to the situation was fight or flight, so I froze, paralyzed by strangeness; transfixed by oddity. The door opening behind me at the other end of the carriage made me jump. Barging confidently through the narrow opening from a dark next carriage with long, clumsy, powerful strides – reason and the world that I’d lived in up until this moment strode into the carriage in the form of a small but powerfully built train guard, hacking to pieces the strangeness like a schoolteacher let loose on a child’s imagination. I sat down to let her pass, and as I did, the man with the briefcase sprung to his feet and, in a shrill and giddy voice, half-whispered to his acolytes:

“She’s coming! She’s coming!”

At once, all the passengers that had been following sprung to their feet, turned tail, and ran in the opposite direction, with the guard following, clenched fists with thudding footsteps. The door at the end of the carriage closed behind her, and the train started moving again. The nervous lady I’d been talking to and the lady who’d come to sit with us all sat wide-eyed in silent disbelief.

The train stopped at Surbiton station. I rushed off with my bike and stood facing the train to see what would happen. It was the final stop – the end of the line for the night. All the passengers got off the train from an even spread of carriages: a man with leather gloves and a rolled-up newspaper, a noisy cluster of teenagers, office people, commuters. Normal people getting off a normal train. Nothing happened.

I rode back, tired and shaken, to my parents’ house, where I slept badly, sweating and rolling like a kebab in my sleep. The next morning, I tried to make sense of what had happened, but I couldn’t really talk to anyone about it, because I just didn’t know how, and it was still too close to reality. My mind belittled the whole thing in self-defense, and as the years went by, I remembered it like a dream, comfortably separate from reality. That is, until a decade or so later, when I developed close to forty rolls of film at the same time that had lain dormant in my parents’ fridge.

The image knocked the wind out of me like a sledgehammer to the chest, shattering the casual embarrassment and nostalgia of looking through photos from a past self. It had mostly come out, with one burned edge at the end of the roll. It was a little blurry from a slow shutter, but most definitely very real. I stared at it to make sure it was real, as though it had somehow been planted. I separated it from the other prints to keep it safe, to study in more detail later, and as a consequence lost the print; but somewhere, in a small blue powder-coated chest of drawers that came from Ikea in the ’90s, in my loft, there, with all the other negatives, carelessly shoved in a drawer, is the negative. It’s the strangest thing that’s ever happened to me, and when my mind wanders on long and lonely rides, I think back to that night and try hard to remember the details, searching my mind for clues. What happened? What does it mean?

This is Not a Bicycle

I don’t feel as old as I am, probably because I’m still more curious than ever. Probably I’m still curious because, where I can, I mostly travel by bike. Curiosity and anger are both so motivating, and I get them from traveling by bike. I can’t imagine how decrepit I’d feel if I walked or knew the answers. I think maybe being a cyclist – or a bike person – is like being an artist. You don’t actually even have to make art in a serious way – if you’re an artist, you just are an artist, because it’s more of a mindset or an ideology or a way of life than it is an activity. If that’s the way you’re wired, it’s virtually inescapable, like a pipe is a pipe or a muscle shell is a muscle shell. If objects in galleries can trans-substantiate, then so can bicycles: they can be dumb sports equipment if you treat them that way, but with the proper respect and ideological space around them, they can become spirit guides that mere pedestrians will never fully understand.

“If you have a golf-ball-sized consciousness, when you read a book, you’ll have a golf-ball-sized understanding; when you look out a window, a golf-ball-sized awareness; when you wake up in the morning, a golf-ball-sized wakefulness; and as you go about your day, a golf-ball-sized inner happiness. But if you can expand that consciousness, make it grow, then when you read that book, you’ll have more understanding; when you look out, more awareness; when you wake up, more wakefulness; and as you go about your day, more inner happiness. You can catch ideas at a deeper level. And creativity really flows. It makes life more like a fantastic game.” – David Lynch