A lot of action over the weekend. I didn’t catch everything, but here’s what I noticed.

Novak Djokovic came from a set down to defeat Lorenzo Musetti 4/6 6/3 7/5 in the final of the Athens 250 to clinch his 101st title.

Musetti came into the final needing to win if he wanted to guarantee his spot in Turin. He came out firing early, launching trademark counterattacks from the deep Aegean blues:

The Musetti backhand is the lone single-hander in the ATP top 20. While it is an aesthetically pleasing stroke, the Italian himself laments the difficulties of facing his double-handed foes in modern conditions:

“I wouldn’t recommend a one-handed backhand to a child starting out because modern tennis is really tough… when it comes to my son, I would want him to have a two-handed backhand.”

— Musetti [ATP Athens Press] / @Zwxsh

The return of serve is often the sore-point for one-handers. Even the counterpunchers are nuking their first serves well over 200 km/h these days, and the lack of prep time and stability requires some work arounds: deeper court positions, more chip and slice. Musetti does both of these things brilliantly, weaving slice and looping topspin from various court positions to disrupt timing via a clever array of altitude changes.

But I’ve also contended that the techniques of recent top one-handers — Musetti and Tsitsipas especially — are sub-optimal for fast conditions. Their high elbow lifts require more time to unwind, and coupled with a lack of backswing depth, add little value to a shot holding on to aesthetics for relevance.

Musetti does at least get the left elbow lower for returns:

Is there a better way?

I believe there is, and we’ll soon find out in the form of young Swiss, Henry Bernet.

Anyway, Musetti does brilliantly with what he has, fusing gifted racquet work with modern movement, and his backhand holds up quite well in rallies. This sliding defensive backhand — which lands conveniently short and low — is a good example.

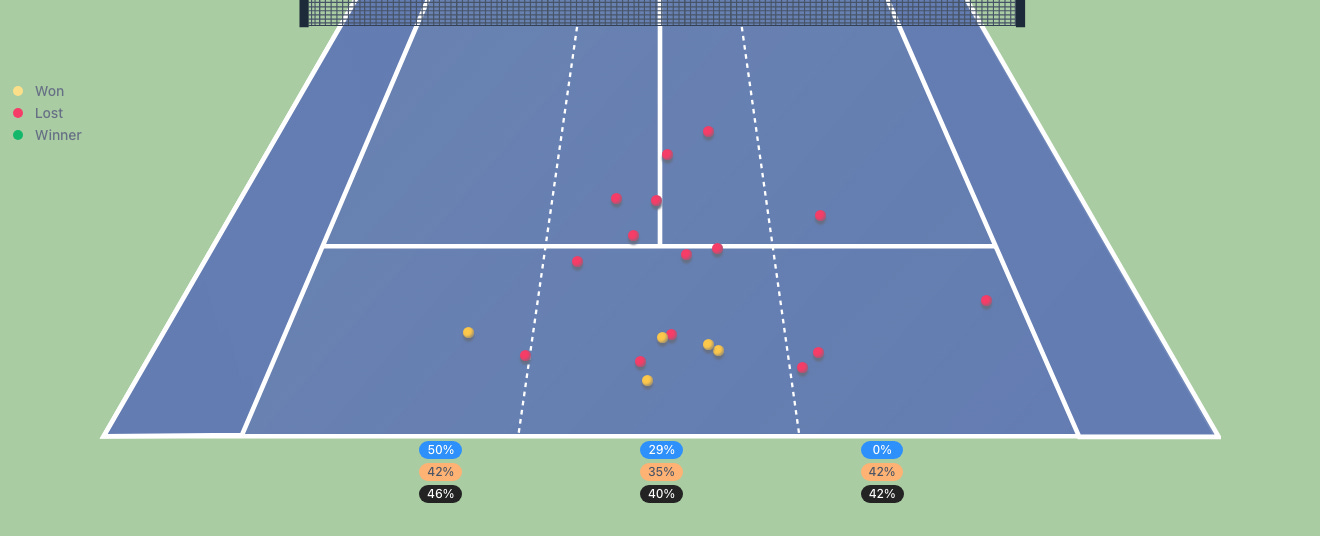

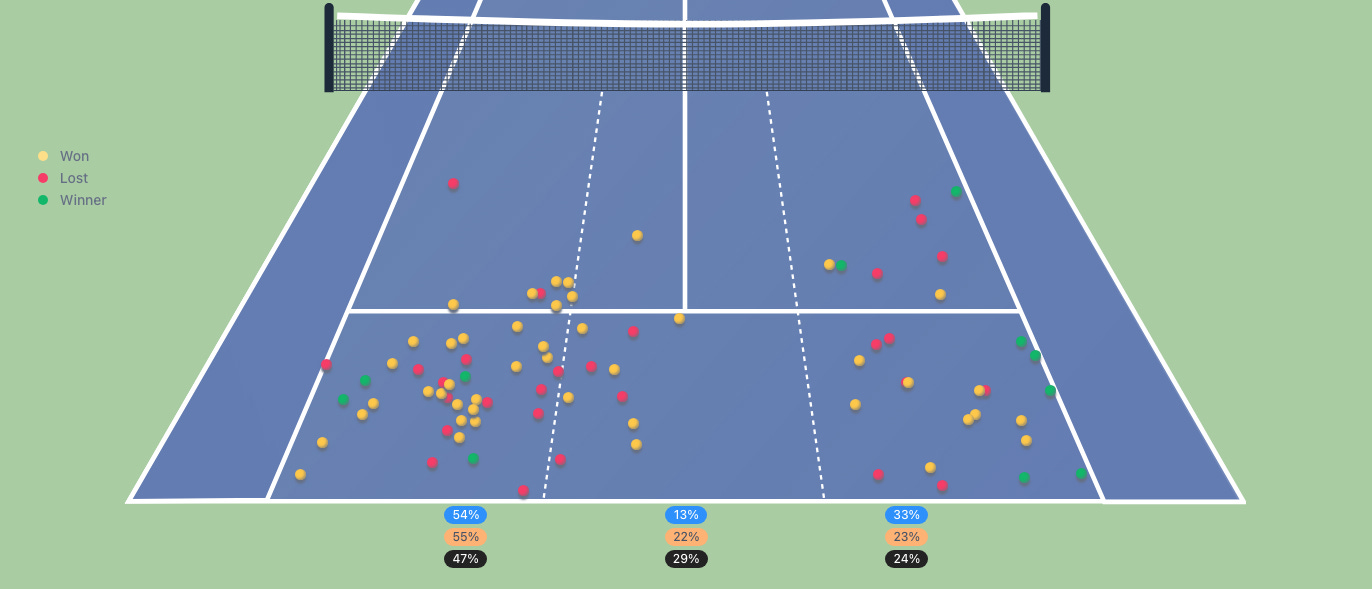

The backhand first-serve return dynamic revealed itself in the data, with Musetti making a lot of his backhand returns, but offering more central forehand +1’s compared to Djokovic, going 5/20 on made returns to these locations. You can bet a lot of these backhands were sliced/chipped (Musetti averaged 55 mph on his first-serve returns, compared to Djokovic’s 63 mph. Their second-serve returns were much closer: Djokovic at 69 mph to Musetti’s 70 mph).

Whereas the Serb was able to spread his made backhand returns against the Italian’s first serve, winning a healthy 50% of these points:

I should point out that chipped returns are not necessarily a bad tactic against Djokovic. If I had to pick a “weakness” in his game, it would be that spin and pace generation are not his strengths (relative to his ability to absorb and redirect, and relative to other tier 1 guys: Federer, Nadal, and more recently Sinner and Alcaraz) and that keeping the ball “stalled” — low and slow — are good measures to thwart his game.

But maybe that’s an outdated analysis. Djokovic has become more offensive and serve-dominant in the latter part of his career, off-setting any declines in movement and rally tolerance that comes with late 30s. This is typical:

Outside the serve-return dynamic, Musetti’s backhand held up well, opting to use the slice 53% of the time and injecting pace on numerous passing shots, but Djokovic has developed the forecourt tools — and maintained the desire — to still overcome these challenges. Check out this incredible 26-shot rally on break point in the second set:

This angle helps you see the how much lower the slice stays. Djokovic is forced to hit from his knees, and this weakens his ability to attack. When Musetti played topspin, Djokovic got the ball above the waist, and this is the wheelhouse of the Serb, able to hit flat and penetrate hardcourts with that relentless precision.

While Djokovic pulled out of Turin, gifting his spot to Musetti, this match summarised the difficulty that the Italian faces on hardcourts: the new generation of Alcaraz, Sinner, and Co. only serve and hit harder and with more spin. Go back to Musetti’s return placement chart and wonder what Sincaraz do to those +1 locations. Protecting his one-handed backhand is nigh impossible on today’s medium-fast hardcourts (he is 1-9 against the duo, with a win on Hamburg’s clay against Alcaraz), and despite his success on the natural surfaces (where he wins 12-15% more matches), the calendar is too thin on points to rely on those events.

Turin is one of the fastest events on tour, and he takes on Taylor Fritz Monday morning. Short on prep time, tired after a long week in Athens, facing one of the elite indoor players, it could be a quick outing.

Carlos Alcaraz defeated Alex de Minaur 7/6 6/2 in his opening round-robin match at the ATP Finals on Sunday.

Alcaraz was humming early on, even by his standards, mincing forehands with enough heat to make de Minaur look pedestrian. These two averaged 96 mph.

But the set piece forehand has always been generationally great. Where the lower setup has paid off for Alcaraz is when pushed wide on defense, or whatever this is:

Given the footspeed and aggressive court position these two hold, the cadence of some rallies produced a kind of auditory tachycardia that drew murmurs from the crowd. You have to have sound to appreciate it:

But I was meant to be talking about Carlos’ backhand.

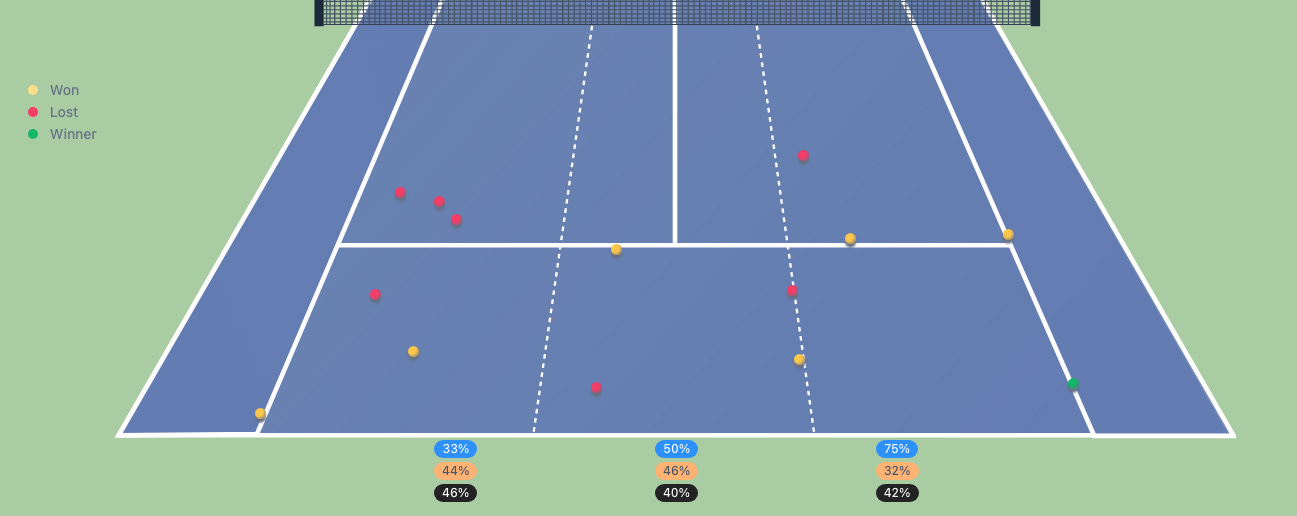

He registered an 8.8 from Tennis Insights on that wing, and he took it down the line 33% of the time in this match — 10% above his own average.

He landed a chain of winners that threaded the line, many coming in the second set:

Here’s one break point. de Minaur just didn’t give this enough juice, and Alcaraz is greedy in his aggression:

Even on defense he was finding corners:

Alcaraz’s backhand has gone through numerous iterations in his young career already, yo-yo-ing between longer and more compact. This was the difference between Australia and Roland Garros this year:

But what he has now seems to perfectly blend prep time with ample power; sometimes he takes it lower (like the above left; check the low backhand off de Minaur’s slice) and sometimes it’s the higher power position (with the racquet head above the hands, like that last winner) that I think facilitates being stronger/more powerful on wide balls when he can’t step into the ball:

I’ll be back with more Turin updates later in the week.

See you in the comments. HC